🎁 Want to give something thoughtful and local that won't end up in Greengairs dump this Christmas? How about a heavily discounted gift subscription to The Bell? Every week, your chosen recipient will receive insightful journalism that keeps them connected to Glasgow — a present that carries on giving all year round.

You can get 44% off a normal annual subscription, or you can buy six month (£39.90) or three month (£19.90) versions too. Just set it up to start on Christmas Day (or whenever you prefer) and we'll do the rest.

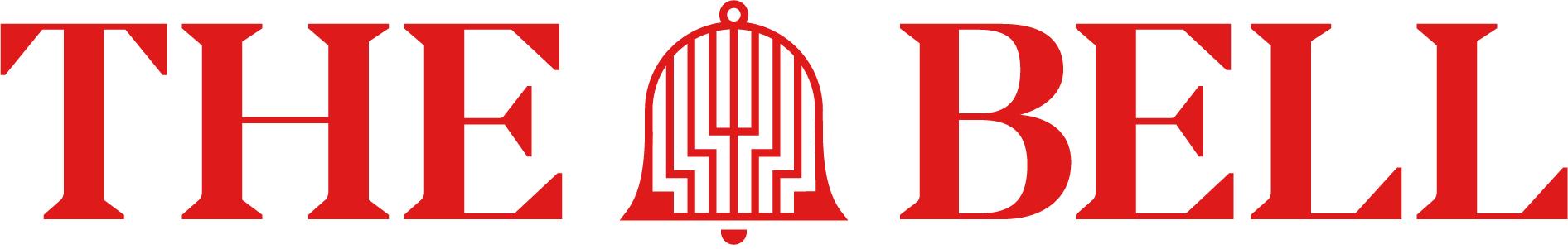

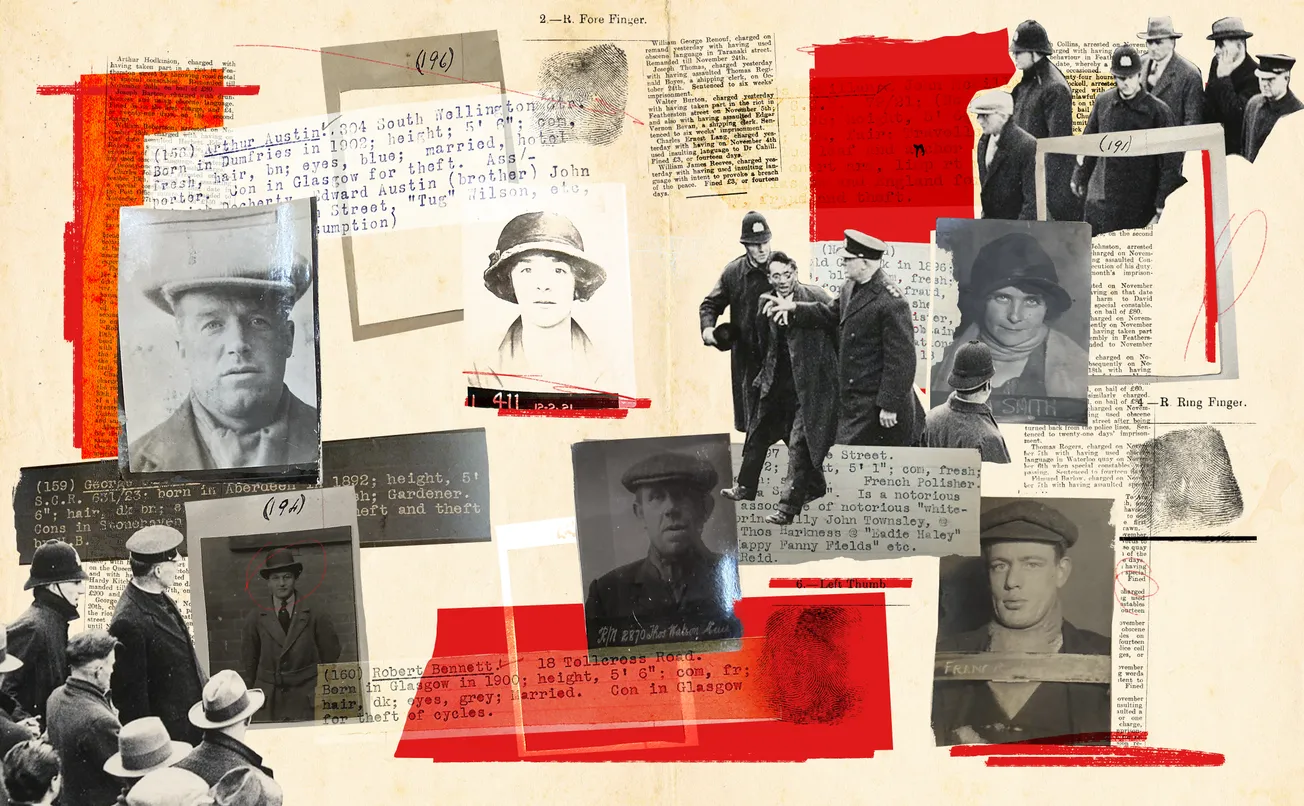

Just over a century ago, a young man named Robert McCartney began compiling a unique photography album. The work comprises over 250 headshots of his fellow Glaswegians, painstakingly glued into the stiff pages of a blue leather-bound book. Today, flicking through that book in the astute surroundings of the Mitchell Library, the pages carry that slightly musty smell of old artefacts, the page texture almost crumbly. Black and white faces stare up at me, many of their expressions surprisingly confident — some outright defiant. It’s a surprise, given the situation the subjects find themselves in.

These pictures portray those who existed on Glasgow’s fringes between 1924 and 1926, the years documented by the album. Sex workers, gay men, people with disabilities and the poor can all be found in the brittle pages of McCartney’s opus. For some, this would have been the first time they had ever been photographed. But McCartney was no artist nor anthropologist. Instead he was a probationary constable, working for the City of Glasgow Police. Yet over two years, with an archivist’s care, McCartney compiled a ‘mugshot book’ about the size of a King James bible, in an attempt to quantify Glasgow’s criminal fraternity.

Unlike a ‘Wanted’ poster, a mugshot book doesn’t refer to live investigations, but records people investigated in the past. The faded legend etched into the blue and gilt of the spine of this album announces it houses the likenesses of: ‘REGISTERED CRIMINALS, Convicted Thieves & their Associates’, ensuring, in the eyes of the police, the subjects were never going to escape their pasts.

Happy snappers

The camera was one of the earliest forms of technology used by the police to identify criminals. No sooner had the permanent photograph been developed than the forces of law and order in Europe were using the medium to make a record of the accused. By 1862, the practice had reached Glasgow and took off — by 1901, the City of Glasgow Police had accumulated over 10,000 black and white images of offenders. McCartney’s album seems particularly unique though, with collected images pasted in the book like a Panini sticker album, accompanied by typed description of their crimes and associates affixed on the opposite page. The constable mainly sourced mugshots from monthly circulations published by the Scottish prison system, or pictures taken in the police station. But he also found personal photographs and even used newspaper clippings to add to his book over the course of two years, from around 1924 to 1926.

It was a live document — at some point McCartney added ‘Detective Constable’ under his name on the inside cover, a rank he didn’t achieve until 1931. Meanwhile, some pictures were cut from the book over time, while others have ‘Deceased’ scrawled across their unhappy faces.

Glasgow in the 1920s was a lot like Glasgow today; the city suffered from lack of housing, insecure employment and poverty. Overcrowding in densely built tenements made this the most congested city in Britain, while the downturn in shipbuilding and heavy industry after the First World War brought mass unemployment, creating fertile ground for crime. Glasgow was considered to be the country’s most dangerous place to live with a reputation that spread internationally —‘No Mean City’, a 1935 novel about razor gangs, was published a few years after McCartney compiled his album. In his 2013 book, ‘City of Gangs’, historian Andrew Davies writes: “Glasgow’s gangs were not unique, but they were more numerous, more entrenched and harder to police than those found elsewhere in Britain.”

Welcome to The Bell. Where else would you read about a 1920s police photo book detailing the city's petty criminals and their marginalised associates? Read on to hear about the ‘petticoat’ housebreaker', Mildred Perpoli.

But first, make sure you never miss an edition by signing up to our mailing list for free. You'll get two free-to-read emails from The Bell every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece like this one.

No card details required. Join the club.

It was also a time of headline-grabbing homicides. Between 1924 and 1925, Glasgow played backdrop to the Maryhill triple murder, the killing of four-year-old Alexander Green and the racially motivated homicide of Norrh Mohammed. Yet somewhat surprisingly, McCartney’s mugshot book is not populated by the gangsters terrorising the population with violence and racketeering, nor murderers and rapists. Instead, the album is a curation of the pettiest of criminals: card sharps, house breakers, bicycle thieves, brothel keepers and gay men (homesexuality wasn’t legalised in Scotland until 1981).

Habitual criminal, Charles Alexander, is a typical inclusion. His mugshot was taken in 1915, when Alexander was imprisoned in Barlinnie. By the time McCartney was recording his latest offence (stealing horsehair from railway cushions to sell on), Alexander had been in the criminal justice system for so long that his photograph was taken via an outdated method. A mirror was placed at the side of his head to capture the 40-year-old at a different angle, with his fingers splayed across his chest to reveal any missing digits.

The closest McCartney’s collaging came to including an actual murderer was Robert Hendry, the prime suspect in the 1921 ‘Sword Street murder’. Sarah Brookstein — a ‘woman of the street’ — had been brutally beaten to death in her Dennistoun home after being threatened repeatedly by Hendry’s co-accused Jessie McMillan, also a prostitute. Hendry was a prostitute’s bully, or pimp, although he maintained his main source of income was running pantomimes. He was picked up by the police after someone recognised him from the description published in the Daily Record, (which was remarkably similar to the description in the book of mugshots). Although he was identified by a number of witnesses the jury couldn’t decide on his guilt and McMillan walked free with him. Press attention around the killing was rabid, due to the lurid combination of sex and violence — the crime remains unsolved today.

In court, Hendry’s lawyer asked expert witness, Professor John Glaister, if crimes of such ferocity were usually committed by foreigners, Glaister replied ‘No’ and added ‘where sexual matters are involved, they more frequently happen to foreigners.” Brookstein’s Jewish ethnicity was regularly referred to throughout the press coverage. In his mugshot, presumably taken at the time of the trial, the smartly dressed, stocky Hendry smiles confidently at the camera. It’s not the expected expression of a man facing the gallows; perhaps he was optimistic a Glasgow jury was unlikely to hang the killer of a Jewish prostitute.

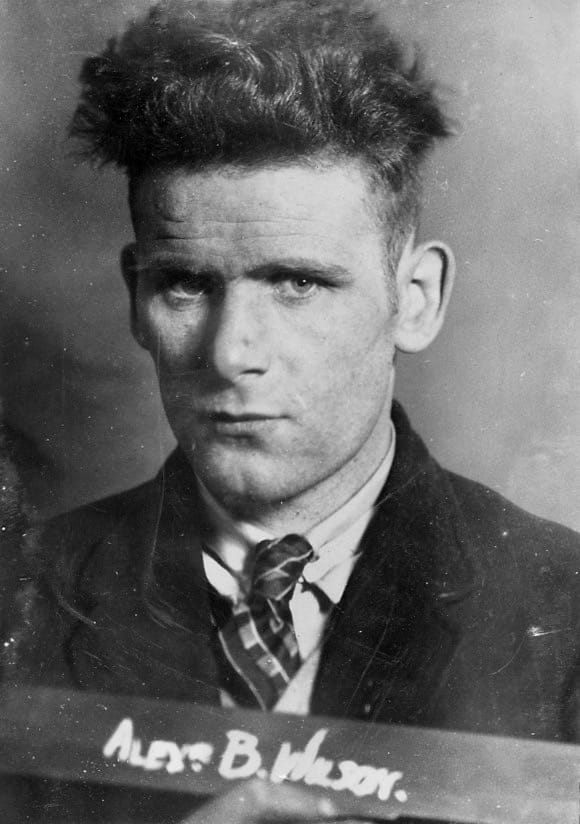

Just as the sexual nature of the Sword Street Murder captured the attention of the press, so too did the transgressive criminal career of Mildred Perpoli, who appears in McCartney’s book just a few pages after Hendry’s photograph. As one of only seven women listed, she stands out amongst the pages of identikit flat-capped Glaswegians. Wearing a cloche hat, Perpoli is a striking 21-year-old woman whose appearances in court drew the attention of the journalists in attendance. ‘Stylish housebreaker’, ‘pretty young woman’, ‘well dressed and attractive’, were just a few observations. One court reporter went as far to describe her complete outfit, down to her brown shoes. Beauty aside, Perpoli’s exploits included an ‘agile and daring’ escape over the walls and washhouses of Paisley while carrying £100 worth of jewellery (over £6,000 in today's money). She was apprehended by a passing constable on reaching street level. One salacious headline writer dubbed her the ‘Petticoat Housebreaker’.

The concept of an audacious female criminal was too much to countenance for the repressive Britain of the 1920s. The gathered media assumed Perpoli had turned to crime after her two-week long marriage to one Charles Gemmell collapsed, causing her to fall amongst bad associates —obviously a woman wouldn’t have the agency to make her own career in crime. Despite her cool demeanour in court, when sentenced to five years penal servitude for housebreaking Perpoli fainted, and was carried out of court by a police officer: normal gender roles had resumed.

By the time Perpoli appeared on McCartney’s pages she had five convictions. Towards the end of the 1920s, she remarried and at some point, moved south, but couldn’t escape from crime. On holiday in Birkdale at the end of World War Two, in June 1945, she stole a silver salver, later recovered from a nearby garden. In court her only plea was to ask for bail to allow her to organise someone to look after her daughter.

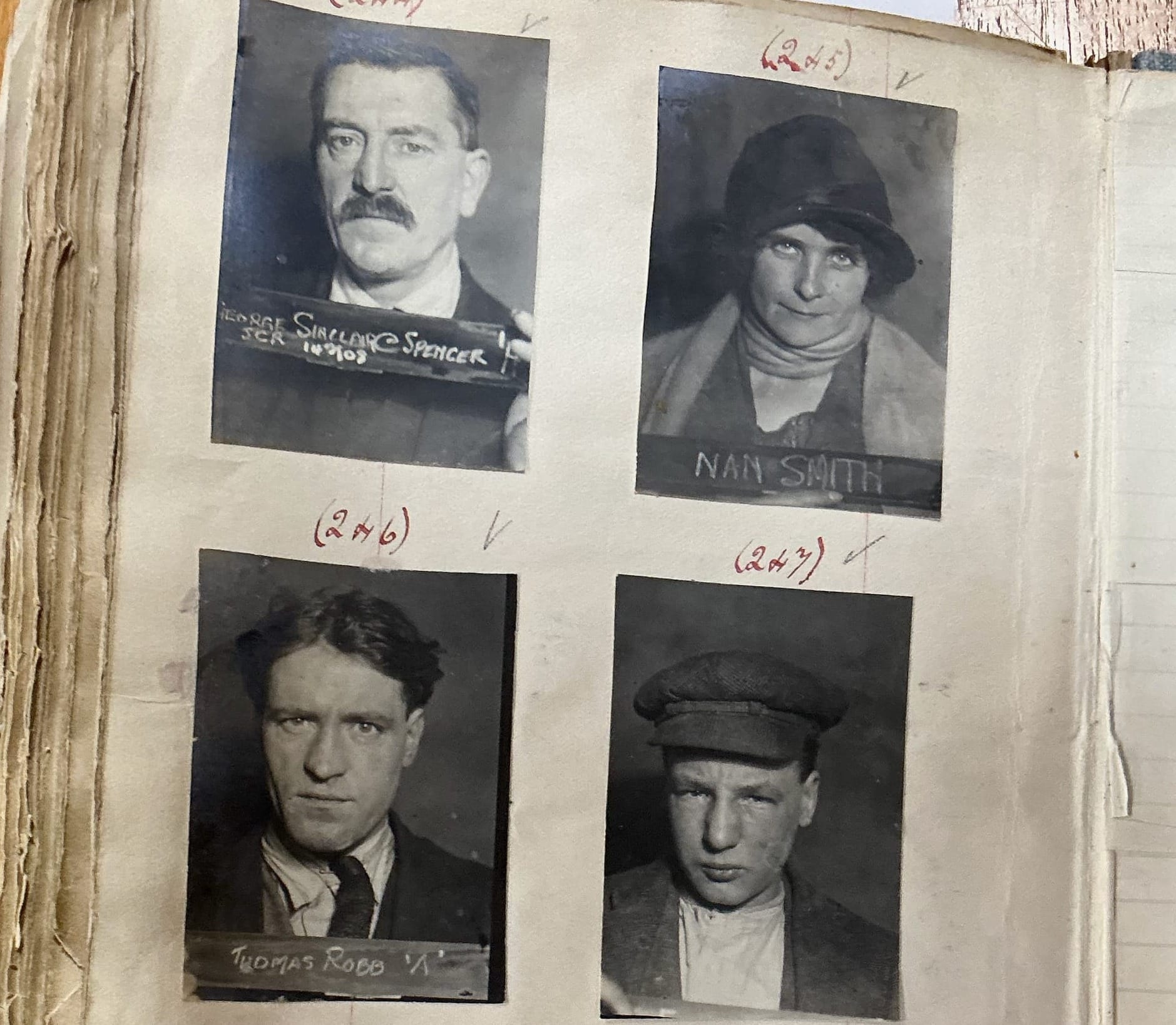

Also mixed in throughout the pages are a group of men known to the detectives as ‘whitehats’. One such ‘whitehat’ was 31-year-old Alexander Wilson. Originally from Kilmarnock, he was well-dressed and could often be found loitering in toilets, theatres, picture houses and dance halls. In his mugshot, Wilson stares at the camera with apprehension, a striking shock of curly hair, like a young Bob Dylan or 1980s indie kid. There appears to be a mark on his forehead — a bruise, perhaps, or maybe a smudge on the camera. The police were not only interested in Wilson because he was gay and a prostitute — he was also accused of being a blackmailer. Whitehats targeted ‘innocent’ men in bars, theatres and toilets for sexual liaisons, then blackmailled them into keeping their sexuality secret. ‘Poof,’ McCartney has written as a descriptor alongside Wilson’s photo.

Whitehats and blackmail

Despite the interwar period carrying the reputation of ‘liberation’, the social climate of Glasgow made it very difficult to be actively gay, explains Dr Jeff Meek, author of ‘Queer Trades, Sex and Society: Male Prostitution and the War on Homosexuality in Interwar Scotland’. The end of the war ushered in a “heightened anxiety around masculinity,” he says. People who didn’t conform to gender expectations were under great scrutiny. Glasgow’s fear of gay men — especially working class ones — even reached Westminster. Local MP, George Buchanan told the House of Commons there was a worrying increase in the trade of sex between men, with a specific type of man at the forefront of these crimes: painted and powdered men, engaging in the dual trade of sex and blackmail.

Despite also being homosexual, whitehats, recounts Meek, played on this societal anxiety. They’d pick up a customer, engage in sex, receive payment, “and then potentially harass that person to get more money out of them.”

Gay working class men were particularly exposed, says Meek, “as there was no routinely accessible commercial gay culture in Glasgow or Edinburgh. For working class men especially, the only avenue they could explore would be in public places — toilets and parks — where they sought solace in the arms of other men.” This exposed them to both extortion and the police.

Sexual blackmail is still a crime which destroys lives and in the 1920s, exposure was an even more terrifying prospect, with no recourse to the law for victims. If a homosexual man’s true identity was revealed, “you would become a marked and tainted person, estranged from friends and family,” says Meek.

Ironically, if a gay man could avoid the clutches of the blackmailers but end up in court he had a better chance of remaining undiscovered by those he had day-to-day dealings with. Such was the general homophobia of the age, his trial wouldn't be covered by the press, due to a law passed in 1926 preventing the reporting of cases which might injure public morals.

🎁 Struggling with the perfect Christmas present? Want something that stands out more than another pair of Edinburgh Woollen Mill socks? The Burrell Collection has some nice pottery, to be fair... BUT, our gift subscriptions are more sustainable, connect the recipient more with Glasgow, and are heavily discounted.

You can get 44% off a normal annual subscription, or you can buy six month (£39.90) or three month (£19.90) versions too. Just set it up to start on Christmas Day (or whenever you prefer) and we'll do the rest.

Give the gift of quality journalism.

But were blackmailers like Wilson — who died in 1974, six years before legislation was passed to decriminalise homosexuality — the exploiters or the exploited? Dr Meek believes that some of whitehats were victims of blackmailers themselves: “There was an association in the period between the wars between specific criminal gangs and prostitution as a whole.”

Gay men were lured into perhaps the most powerful organisations of the day within Glasgow communities, the razor gangs. And just as today’s gangs exploit legislation which makes drugs illegal, so too would organised criminals of the past use blackmail as a tool for extorting money. One such victim-cum-perpetrator might well have been Thomas Robb, from the Calton, who also makes an appearance in McCartney’s book. His alias of ‘Maria Santoy’ linked him to the San Toy razor gang from the same area. Had they discovered Robb’s sexuality and decided to pressure him into becoming a blackmailer?

Unlike the other professionally printed albums held in the Mitchell’s police archives, McCartney’s home-made version is strikingly personal. That’s why it stands out to me; in their suit jackets, neckerchiefs poking through, the Glaswegians in his book are straight off the interwar streets. This curio is a window in time. Far more than a rogue’s gallery, it’s a document of a group of down-on-their-luck individuals who deserve a place in the city’s much-storied history, as much as the merchants whose names adorn our streets, or the gang members we love to mythologise.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.