The weed-strewn red ash football pitches at the foot of Hamilton town centre shimmered in the morning heat. For one weekend they would be repurposed as a coach park for the tour buses of the great and good of the British music scene. It was to be a scorching day, as the second heatwave to descend on Glasgow that summer reached a crescendo. By 11am the festival’s gates were open and in the absence of music, early arrivals milled uncertainly or slumped on the grass in front of the main stage. Chris Miezitis, singer and guitarist with Fife band the Diggers wryly recalls hearing of some aggro at the main entrance, “It was a bit of a clash of cultures,” he says. “Glasgow indie kids meeting Hamilton's local Buckfast worshippers.”

A few miles away, Strathclyde Police had already been at work for several hours. Detectives had been summoned in the early hours of the morning to a property at 20 Young Terrace in Springburn. There, they had discovered the body of 36-year-old John Sawers, dead from a neck injury in the living room of his own home.

He had been punched in the throat during a party to celebrate his mother-in-law’s wedding. By the time the first festival attendees were queuing to enter the site, police would have two people in custody in connection with his murder.

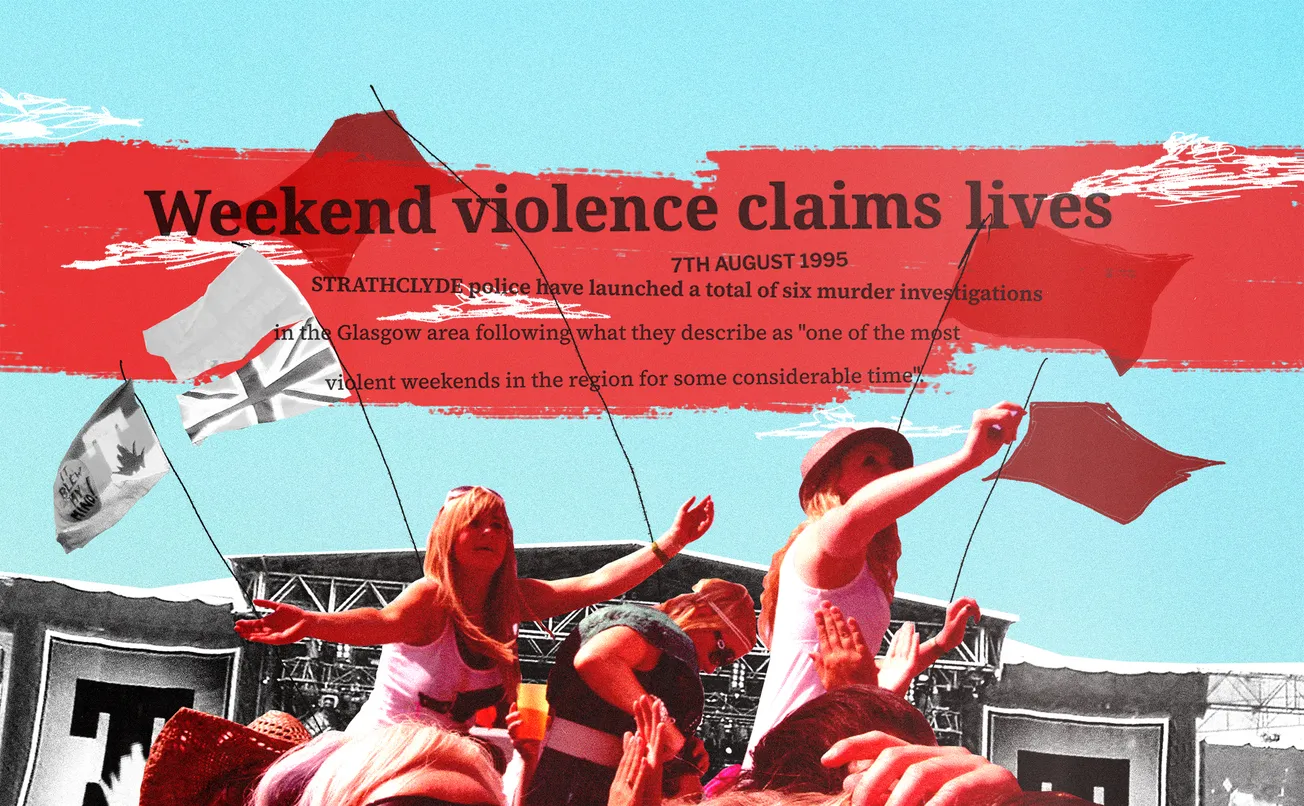

It was the first killing of a weekend that would sear itself into the collective consciousness of Glasgow; where tens of thousands of young Glaswegians would have their first taste of the festival experience, while others would be enveloped in darkness, as violence boiled over on the city’s streets.

Fancy more untold stories along with essential news direct to your inbox? Three days a week, we send you a carefully chosen story plus our best scoops, investigations, and recommendations. We prioritise quality over quantity and everything we send is in your emails — just click the button below to join our free mailing list. That's it: no ads, no spam, no nonsense.

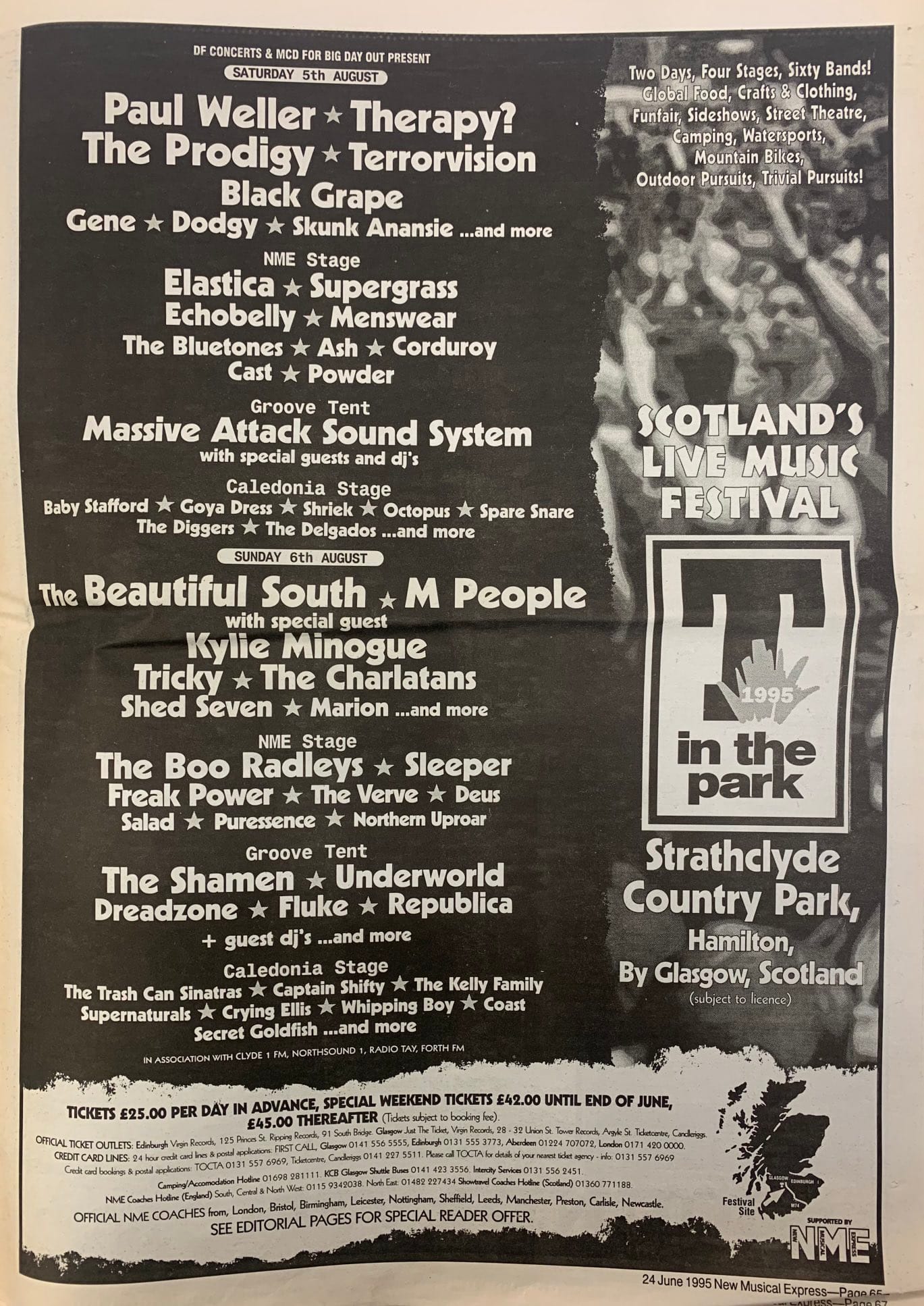

1995 was the second year of T in the Park. Previously the festival experience had been out of reach for most young Glaswegian music fans due to a combination of cost and inaccessibility; the closest major festival prior to T in the Park was the Phoenix Festival, a six-hour drive from Glasgow. Seeing live music at all was a challenge. Unlike today, all-ages shows were simply not a thing, and music venues in the city centre had strictly enforced age restrictions, with some insisting on a valid passport for ID.

The bill was littered with Britpop bands who attracted large and passionate audiences. The festival took place at what was the zenith of the era; the following week would see the most infamous manifestation of this, with the scene’s two standard bearers, Blur and Oasis, releasing competing singles in a battle for the number one spot in the charts, with the former emerging triumphant.

The movement had already reached its creative high watermark, as it became plagued by bandwagon-jumpers peddling an increasingly narrow facsimile of Britishness. Nonetheless, many celebrities were still present at the festival. Oasis guitarist Noel Gallagher was backstage having tagged along with his mentor Paul Weller and would appear during the latter’s set on the Saturday evening. More randomly, Scotland striker Ally McCoist, looking to transition to a media career, appears with his arm draped chummily over a range of celebrities in backstage photos, among them a befuddled looking Robbie Williams, indulging in an extended lost weekend following his departure from Take That.

Away from the celebrity excess, tucked away in a far corner of the site, interesting things were happening on the Caledonia Stage. Essentially a showcase for local acts, a “token gesture”, as Spare Snare frontman Jan Burnett suggested, the stage presented a chaotic amalgam ranging from hard rock (former Gun guitarist Baby Stafford) to Britpop upstarts (the Supernaturals) to down-on-their-luck local heroes (the Trashcan Sinatras). Dotted among these however were some of an emerging generation of new Scottish bands inspired by British Post Punk and the DIY ethos of American indie labels. These groups were members of what the music press would clumsily dub “The New Scottish Underground,” a scene rooted in the venues, record labels and fanzines of Glasgow’s fertile creative scene.

Burnett’s memories of the festival do not tally with the glamourous backstage images that were splashed across the tabloids. Spare Snare arrived in a van driven from Dundee by Burnett’s uncle, picking up friends and partners along the way. Backstage, the band’s multi-instrumentalist Alan Cormack had time for at least one edifying celebrity moment when he encountered Clash legend Joe Strummer. By the end of their conversation, Strummer had scribbled his address on Cormack’s shirt for him to post on a copy of the group’s debut album, while complimenting Cormack on the band’s name. “We’ll take that,” noted Burnett.

For other up and coming bands, the glamour was more pronounced. Miezitis recalls that the Diggers spent their fee on a room in the Glasgow Hilton, where many acts were staying on the Saturday night. On the Sunday morning, after a night celebrating a good performance, he found himself queuing for breakfast next to Kylie Minogue: “I hadn’t slept all night, so I felt and looked like an extra from Rab C. Nesbitt while she looked like, well, Kylie”.

"Society is disintegrating"

As dusk fell on Strathclyde Park, and the big names at the top end of the bill started taking to the stage, a few miles away violence was fomenting in the city. Police were summoned to a disturbance at Mansewood, where they found 26-year-old former soldier James Boyce dying in the street from a stab wound to his chest. A man was arrested at the scene. An hour later a similar call from Possilpark: witnesses watched as an unidentified man walked up to 39-year-old Billy Downie and, without saying a word, fatally stabbed Downie in the throat before disappearing into a side-street.

At around the same time the Prodigy were closing the main stage for the night. The group had already transitioned from stalwarts of the Essex rave scene to festival headliners. Video of the night shows the stage is illuminated by a spectacular lightshow, however, it is the audience that catches the eye. As Keith Flint dives into the crowd, stage lights pick out a seething morass of bodies in the background. A zoomed-out view is even more striking, as the sheer scale of the crowd becomes apparent; even for a festival it is enormous. There are no camera phones and no banners, just a sea of people moving in time to the music.

Sunday Morning dawned bright and true over the campsite. But not before the night had brought more horror to Glasgow’s streets.

Around 1:00am, 46-year-old Easterhouse native John McFarlane was attacked in the street and stabbed to death by a gang of youths, three of whom were swiftly arrested. Murder number five of the weekend occurred at 3:00am when Alex Donnelly was left bleeding to death in the stairwell of a tenement block in Petershill. Just an hour later, the weekend’s bloody business would conclude as 20-year-old Brian McVicar died after being attacked by a gang in Clydebank.

It was a weekend of unprecedented violence, and the handwringing soon began. The Daily Record’s headline spoke volumes — “The Curse of No Mean City”. A Garden Festival, the European City of Culture, a knife amnesty, and now a major music festival on its doorstep, yet Glasgow still struggled to cast off its miasma of violence.

Labour home affairs spokesperson John McFall curtly attributed the violence to “drugs culture.” Dr. Alan Fraser of Glasgow University was more circumspect, suggesting that the tendency of people to congregate in public spaces during hot weather, coupled with increased alcohol consumption was likely a driver behind the violence. George Galloway, at that time MP for Glasgow Hillhead, struck a wholly pessimistic note: “the very core of our society is disintegrating before our eyes”.

At T in the Park the Sunday was comparatively subdued, with the feeling of a gentle, but nonetheless tangible, hangover.

Still there was drama to be had. The Verve took to the second stage late in the afternoon off the back of strong critical notices for their second album, A Northern Soul. Stardom seemed inevitable. Their performance was intense, but also devoid of their album’s more accessible moments. Instead, led by guitarist Nick McCabe they served up a swirling psychedelic wall of sound while vocalist Richard Ashcroft incanted over the top. At the close of their set, the now barefoot Ashcroft hurled his shoes into the crowd as the band stomped off amidst wailing feedback. The following Wednesday, the weekly music press announced that the Verve had split up immediately following the show. A month later they would release an elegiac final single, “History”, its sleeve bearing the legend “All Goodbyes Should be Sudden”.

By this point, Strathclyde Police had culprits in custody for all six of the weekend’s murders. These were not the acts of criminal masterminds. These were wild, impulsive crimes driven by anger, drink, and desperation.

Despite the words of politicians like McFall and Galloway, by 1995 tentative recognition of the true causes of Glasgow’s epidemic of violence were emerging. In the Scotsman that week, Richard Kinsey, an academic at the University of Deeside, noted that factors such as inequality and poverty needed to start being considered as the root of violent crime. This idea would gain credence over the following decade and would form a key element of the violence reduction strategy which would be so effective in the coming years.

Asked if T in the Park 1995 felt like a coming moment for the Scottish music scene Burnett emphatically replies in the negative: “it was fun though”. Spare Snare continue to record and play live, their twelfth album, The Brutal, was released in 2023.

For some it was the beginning of the end. Despite their show being sabotaged by detuned guitars, The Diggers impressed one key audience member, Creation Records owner Alan McGee. The band were signed, lined up for several high-profile support slots and rushed into the studio to record their debut album. Mount Everest was released in spring 1997, but by this point the band, barely out of their teens, had “imploded internally”. Miezitis remembers, “we never really had anyone looking out for us; we were naïve kids in a world of predatory adults, in among some genuinely nice people”.

The Verve would reform in 1997 and go on to considerable commercial success.

T in the Park’s 1997 relocation to Perthshire would change the dynamic of the festival. It continued to grow however and attracted upwards of 85,000 people each day by the early 2010s.

However, anti-social behaviour bedevilled the festival. Things came to a head in 2016; problems that had emerged in the campsite in previous years had become too much to ignore. There were thefts, sexual assaults and pitched battles. Two teenagers died, allegedly due to a tainted batch of ecstasy. The festival went on hiatus for 2017. It has never returned.

There is nothing to mark the site of the first three festivals, the portion of Strathclyde Park in Hamilton was given over to developers in the late 1990s. Today a retail park stands on the festival site. But for a generation of Glaswegians the site indelibly marks their induction into the world of rock and roll.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Bell and reach over 10,000 readers, you can get in touch at grace@millmediaco.uk or visit our advertising page below.

Liked Iain's story? Remember, if you want more weekend reads and essential Monday briefings straight to your inbox, it's free to sign up to The Bell.