I rarely have cause to walk down the section of Argyle Street guillotined off from the rest of the city by the bridges of Central Station and Kingston these days. When I do, a sense of foreboding accompanies the approach to Kentigern House. Now dwarfed by the financial super-structures of the Morgan Stanley and Sentinel buildings, this strange, toad-like building played a remarkable role in transforming Glasgow from its dying industrial past to its present-day service sector status when it was built some 40 years ago, when over 1,000 Ministry of Defence clerical jobs were transferred to the city from towns across England.

I know this building well, its corridors and lifts, work stations and toilets. I was part of the first cohort of Civil Servants employed here in September 1986; I was also the first to be dismissed 198 days later, given 10 minutes to clear my desk and then escorted off the premises by two towering MoD police officers.

The level of state intervention necessary to move the work I so carelessly lost seems incredible today, yet the job transfer could have been even bigger. It was planned to be “the largest transfer of Civil Service jobs in peace time Britain,” according to the Times. The original scheme, outlined in the Hardman report published in 1973, would have moved the entire civil service out of their expensive premises in London to be dispersed to the more affordable provinces. This was eventually whittled down to relocating the department entrusted with the country’s defence to Glasgow, in an attempt to soften the blow of shipyard and steelwork closures.

Yet Whitehall mandarins even found reasons to block this smaller shift, combining fears over security and Caledonian nationalism with a dose of anti-Scottish prejudice. In August 1974, The Times reported the MoD was “considered one of the elite Whitehall departments in terms of prestige and promotion opportunities,” which would be lost far from the centre of power north of the border. The article continued that those at the top of the organisation were accustomed to London and it would be impossible to find volunteers due to the poor housing and lack of “bright lights” here. Put simply, it was not a nice place: “If you take your child to Glasgow, he is going to suffer from leg pulling; they speak with the wrong sort of accent. There is fear of considerable clannishness on the part of the Glaswegians,” according to an 1983 Times article.

The government plans diluted the 6,000 jobs to 4,500, and eventually just 1,400 positions, not taken from central London but provincial towns like Hastings, Reading and Brighton which had their own unemployment problems. Along with around 60 others, I was dispersed to the latter town for just under a year in 1986, training as a Posting Officer for the Royal Engineers. The Civil Service were keen for this to succeed; we were paid a generous allowance and could fly back to Glasgow every weekend if we liked, all at the state’s expense.

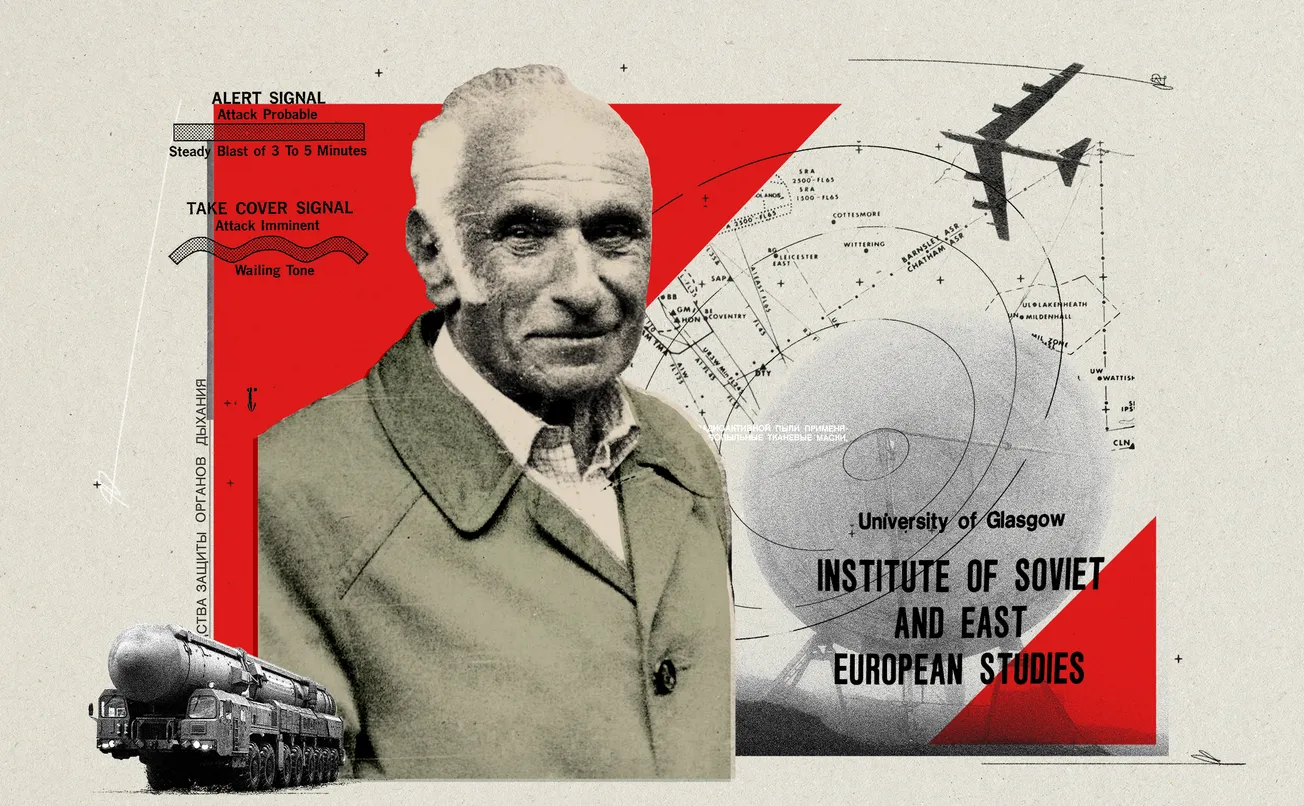

The largesse spent on lowly clerical officers was matched by the money spent on the building we would eventually be housed in. At a reported cost of £19m, Kentigern House was at the time the largest office development outside London, with 22,500 square metres of floor space. This inwardly sloping modern castle with a dry moat rose to six levels of stifling office space built around an inner courtyard, supposedly created for repelling missiles with massive brick ramparts protecting inset unopenable thick-glass windows. A basement as deep as the height of the building was rumoured to have been constructed underneath: six floors of subterranean record keeping and a nuclear fall-out shelter with a gym for military personnel only. I can only confirm the lifts I rode went no further than G.

Hi, we hope you're having a nice weekend and we trust that Gordon's first-hand account of getting fired by the MoD is adding to it all.

We’re The Bell, Glasgow's new newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Bell every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about what’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece.

No gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

As surprised as I was to be fired, I was equally astounded at getting hired, as I was a college drop-out with few qualifications and no office experience. During the interview process I was asked how I would cope working under a female supervisor. My assurances to the interview panel I wouldn’t find this problematic perhaps swung it for me, it certainly wasn’t due to the part in the process when they asked about my outside interests. I wasn’t a member of any organisation nor did I do any sports but I was obsessed with music. The hippest member of the panel must have thought I had invented the name of my favourite band as one of my future colleagues was asked if he had ever heard of the Jesus and Mary Chain when it was his turn to be interviewed.

But then maybe I fulfilled a criteria I wasn’t even aware of. In January 1985 almost a fifth of the working population in Scotland were unemployed. By October, just after I had turned 19, the age group most likely to be unemployed were between 18 and 24, which was the age range of most of the clerical workers I began working with the following month. My other trump card was my postcode which placed me in the east end of Glasgow — maybe I had been positively discriminated?

All MoD cons

While working for the MoD didn’t work out for me, it did for the city. Coupled with the successful but cringy Glasgow’s Miles Better advertising campaign, it shifted from the ‘No Mean City’ stereotype to being awarded the City of Culture in 1990.

But as office work became Glasgow’s new industry, a new industrial injury developed. Not as romantic as a missing digit caught in a lathe, Sick Building Syndrome was recognised as a disease by the World Health Organisation the same year Kentigern House opened. The main symptom was a dull throbbing headache, making it difficult to concentrate on the drudgery of work. While the exterior might save us from a mortar assault, inside our senses were attacked causing itchy, runny, blocked noses and irritated eyes which were either watering or too dry. The one element I found hardest to overcome was the constant lethargy. I just assumed it was my anathema to working which made me feel this way but by afternoon, I felt so tired I could have fallen asleep on my desk.

Perhaps most tellingly it was found “people with the most symptoms have the least perceived control over their environment”. Such was our lack of agency in the MoD; staff were stopped from bringing in kettles and toasters to use during breaks at their work stations — daily take away coffees and sandwiches were beyond the budget of the humble civil servant. I think the official reason given was a fire hazard but the consensus of office opinion switched between the small kitchen appliance ban being introduced to encourage use of the work canteen five floors below or to save electricity in a government department reeling from the costs of the office transfer. It let the staff clearly know their position in the building; we couldn’t even control what we could consume at work.

When I was called into the head of establishment’s office, I assumed it was to rubber stamp the end of my probationary period as a Civil Servant. It had been extended a few months and I had dropped down a grade from Clerical Officer to Administrative Officer, but such was my obliviousness, I genuinely didn’t expect to be let go. No explicit reason was given, just a chat about the work not really suiting me, and when I applied for my records decades after I left, it only states I resigned my post — I didn’t.

I had been a union secretary in an organisation which was definitely anti-union but so were lots of others who hadn’t been dismissed. Whenever a friend phoned my office line he generally signed off the call with a jokey “up the ‘RA’” but I naively thought they wouldn’t tap the phone of someone in such a lowly position. My time keeping was atrocious but we were all on flexitime, allowing staff to turn up at any time before 10.30AM. Admittedly, I did struggle to make up the time as it would have meant staying late in the office alone with the new boss, a retired Major I didn’t get on with. At one point, he told me to spend less time away from my desk, which I took exception to. The open plan nature of the office possibly meant he heard me calling him some choice names on a number of occasions.

Of the thousand plus people who worked there: the crowd I would head in with in the morning, the lady who couldn’t remember anyone’s name, the guy who smeared the contents of his nose on the toilet door every day — all had passed the test but I had come out bottom of the class. I was embarrassed to think how my performance as a civil servant had been appraised over the previous 17 months.

Quick reminder: you can sign up to The Bell entirely for free.

Just click the button below, pop in your email address and you'll get two free editions every week that'll keep you up to date about Glasgow's goings on and show you a side to the city you haven't seen before. Enjoy!

My 'McJob'

As part of the procedure to claim unemployment benefit, I had to regularly attend a Restart interview at the Job Centre. At the first meeting I was asked what I was experienced in. When I said ‘clerical’ the interviewer reached into his filing cabinet for a couple of potential openings, as I casually mentioned I had been sacked from the Civil Service, he nearly fell off his swivel chair.

It wouldn’t be for another five years before Canadian writer Douglas Coupland coined the term McJob, defined as a “low-pay, low-prestige, low-dignity, low-benefit, no future job in the service sector”. If ‘service sector’ was switched to ‘public sector’, Coupland perfectly defined my work in the parts of the Ministry of Defence that those in government deemed were not crucial to national security and could be safely dispersed North.

While the government might have considered themselves benevolent by extending this patronage towards me — after all I wasn’t exactly the full employable package — I thought I wasn’t doing my job properly, which gave me the underlying feeling of anxiety I was about to be found out. I didn’t have the self-efficacy to find out if there was anything else I should be doing. In reality, the position was almost certainly constructed to take people off the unemployment figures. It doesn’t seem a stretch that a government who would routinely massage unemployment figures for political gain, would also continue non-jobs to lower the overall rate of those not working in political hotspots like Glasgow.

There’s not much sign of life around 65 Brown Street today. Although flags flap in the wind on the flagpoles which I don’t remember ever being used when I worked there, a ‘Do Not Enter’ sign is stuck on the door I was unceremoniously booted out of. One flag simply says ‘ARMY’ and it seems a section of the building is still used for different military offices.

When I retreated along Argyle Street on 17th March 1987, I toyed with the idea of becoming one of those shadowy figures, hated both by the right-wing press and politicians alike, a workshy benefit scrounger taking the money out of the pockets of hard-working, tax-paying families until I could ‘retire’ and claim my state pension. It didn’t pan out like that. Instead, my life since then has been structured by work, carried out for the last four decades in three different countries; book-keeping, dishwashing, writing, cheffing, selling, teaching… I thought I didn’t care about being fired, it was a story to tell and nothing else, but the stain must have remained within me. It took me a long time to realise I wasn’t defined by something that happened when I was 20 — but actually a contributor to society.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Bell and reach over 11,000 readers, you can get in touch or visit our advertising page below.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.