Let’s start with a happy, true story of Glasgow dogs and humans past.

A few years before the pandemic, Glasgow City Council's dog wardens got a call to pick up a dog from someone’s garden – a wee Jack Russell who had been found running about loose in the street.

The dog warden turned up and scanned the little fellow, discovering that his chip number was registered to a family in another local authority area. They contacted the owners by phone, who thought it was a hoax call, since the dog had been missing for two whole years. A joyful reunion followed. Wag! Woof! Job done.

This feelgood tale was relayed by Glasgow City Council on Facebook in 2021, as part of an awareness campaign for its “dedicated dog warden” service. Covid-19 had created a surge in dog ownership nationwide, and Glasgow parks were suddenly full of unruly puppies. (My own disobedient example included.) The visible “daytime” population of adult dogs also increased as people worked from home and owners spent more time outdoors with their pets. There had arguably never been a greater need for council employees who understood dogs and dog-related legislation to help the city care for them when things went wrong.

In the present, the picture looks quite different. If that Jack Russell were to find himself lost in Glasgow today, there would be no one for a good Samaritan to call. At least, no one at Glasgow City Council.

As of a few months ago, the council suspended its dog warden service “until further notice”. Instead, the council directs people towards Police Scotland to report dog control issues, and suggests that lost dogs be taken to a local veterinary surgery to be scanned for microchip details. Though not mentioned by the council, the reality is that Facebook itself is also likely to be a first port of call when trying to locate or reunite a canine separated from its owner.

Can this be right, I wondered. Glasgow is a dog-daft city: my own furry friend is on first-name terms with many of the local cafe owners and shopkeepers, and has an unspoken deal concerning free ham at my daily coffee stop.

I had a nasty flashback to the moment a few years back when I hit a dog training low. My mutt, who has a passionate fear of bicycles, decided to take off when he saw a cyclist unexpectedly approaching through a normally dog-only part of the park. I spent a whole morning trying to catch him and ended up calling friends who lived nearby to help corner him. Mercifully that worked. But the dog warden was going to be my next panicky port of call.

Could the city really be without a dog warden? More to the point, is it safe?

I called the council’s switchboard, asking for the dog warden, to check if it was true. There wasn’t a dog warden any longer, I was told, but to their credit, the call handlers were reluctant to not offer any help at all, and so I was passed further and further down a warren of telephone extensions answered by departments who all referred me on to others. No one had a clear idea of what to do.

Hello, welcome to The Bell, Glasgow's new quality newspaper. Delivered via email, join our free mailing list to get two full editions a week: a Monday briefing, full of things to do and bitesize news, straight from the dear green streets, and a weekend feature, taking you deep inside the bowels of Glasgow.

To get total access to all of our weekly editions, you can join up as a paying member. We'd love that. But we understand you might want to try before you buy, so click below to sign up totally free and start getting our special brand of local journalism straight to your inbox today.

After trying the switchboard, a few days later I reached an official at Glasgow City Council’s press office. They offered an explanation, of sorts. “We do still have dog wardens,” they insisted, adding “dog wardens include the work of pest control.” This effectively makes them environmental wardens, sorting out bees, wasps and vermin, as well as rounding up stray dogs. “There’s an issue with the kennels where we’d take the dogs,” the spokesperson continued. “The kennel service we contracted [at SPCA Cardonald] has ended the contract. We are trying to identify other kennels and have suspended the service in the interim.”

Is that a cost issue? I ask. Not sure, is the answer. Meanwhile, the spokesperson noted that “We do have a dog control officer - enforcing the Dog Control Act. They liaise with Police Scotland. We accept there is a confusion – most authorities do have staff who enforce dog control who also work as dog wardens, but we’ve decided to do it a wee bit differently.”

The conversation ends with an aside about how other local authorities also appear to be struggling to maintain dog-warden services. I check Whatdotheyknow.com, the directory of Freedom of Information Requests, and find a steady stream of people writing to councils around the UK to ask how many dog wardens are on staff. “None” is one of the more common responses.

A spokesperson for the SPCA did get back to me, and they confirmed that they ended their stray dog service contracts so they could focus on their “core animal welfare services”. “We gave notice to the police and local authorities in 2024 to ensure there was time to make alternative arrangements,” they finished. Those arrangements don’t appear to have materialised in Glasgow.

Have you got a licence for that?

If a mutt were to look at a map of Glasgow, the prospects of a cool dog life appear pretty promising. Green space – big chunks of it – is dotted around the city at frequent intervals. Not too many humans or cars. Not too hot in summer. Plenty of squirrels. Dog sausages, muffins and milky drinks on the menu at a luxurious proportion of cafes. It feels like one of the more logical cities in which to be a dog – unlike, say, New York, where bigger hounds have to be carried in bags on the Subway and all dogs are on-leash everywhere.

The reality, as we know, is that dogs can’t choose their cities or their owners. Our canine culture is a direct reflection of who we are.

One person in Holyrood who has taken action on the wider problem of canine care is Christine Grahame, MSP for Midlothian South, Tweeddale and Lauderdale.

At her instigation, the Scottish Parliament this year passed a new Welfare of Dogs Bill (Scotland), which comes into effect in 2026 and will change the nature of dog ownership. To buy a dog here, you will need to get a certificate of ownership, following a similar system already enforced in France. (And partly reviving the “dog licence” that used to be a paid requirement in the UK, until it was abolished in 1987.)

The idea is to create some accountability in what is currently a wild west of dog-buying and owning. Bound up in the paperwork is a kind of social contract that requires dog-buyers to think ahead about the reality of what they’re getting into. “If you like, it’s ‘terms and conditions’,” Grahame says. “Look at the interrogation you have to make of yourself and your motives, and also those of the supplier.” And if a dog is then flagged as a danger to themselves or others, an owner must be able to produce the certificate.

We’re used to horror stories of out-of-control dogs mauling people and causing chaos – the end result of what Grahame describes as “thoughtless” dog ownership, when someone has not prepared for the demands of their chosen breed, and may not be capable or really willing to give due care to the animal. In Tinto View, Hamilton, last year, for example, armed police shot dead a “large, bulldog-type dog” that attacked and seriously injured two people and attempted to bite a police officer. An eyewitness told BBC Scotland that "I think the first guy had been bitten and the other guy was trying to get him off. Eventually they got the dog off him but then the dog turned on his owner and grabbed hold of him and just didn't let go. It was pretty brutal."

However, Grahame tells me she had become “concerned at the portrayal of the dog as the villain and not the person on the other end of the lead... Most of the time the issue is ignorance on the part of the owner, or the fact that the puppy was an ‘accessory’ and once out of the cutesy phase, not tolerated.”

Her emphasis, she says, has always been on “the deed not the breed”, and “putting responsibility on the owner – where it belongs”. She adds: “I think the Dangerous Dogs Act is bad law. The latest bad law being the law regarding American Pit Bull Type dogs – not even a breed. I opposed this and tried to have it disregarded at the committee. Political law is nearly always bad law.”

Grahame is also aware of the enforcement problems on the ground. “I have had quite a few meetings with members of the Association of Dog Wardens and am concerned that they are not valued. In some cases I know that councils pass this responsibility to environmental wardens. As wardens sometimes have to confront very difficult owners, I also was concerned that nearly always they are out on their own.”

The UK has an estimated 12 million dogs, and, it seems, an increasingly rare breed of dog wardens. As Grahame points out, there is an element of risk undertaken by the warden. But in theory, they’re not just Dickensian figures who round-up naughty, stray dogs into a van, or even simply heroes saving Jack Russells, as happened earlier in this story. The dog warden, in a model society, is supposed to teach people what it’s like to own a dog: the good, bad, and barking mad aspects included.

This point underpins the Welfare of Dogs Bill. You must know what you’re getting yourself into. “The legislation was not to be punitive but educational,” Grahame says.

'Sorry, but it’s three barks and you’re out'

Grahame’s words remind me of the very long summer of 2021, when I learnt, mostly the hard way, how endlessly my puppy enjoyed making mischief and creating havoc out of thin air – gleefully ignoring my sobs and cries as I chased him in circles around the park. I can see my former self, in slow motion, stepping into all the pitfalls that Grahame now wants people to avoid. I hadn’t fully researched the breed, its exercise needs, the costs, the time, the all-round commitment, and I had a hopelessly optimistic view of dog training. (Mostly involving meaty treats, YouTube tutorials and thousands of biscuits.)

As the dog settled down (it must be said, slowly), I took him almost everywhere with me – amazed as he was allowed into shops, pharmacies, pub quizzes and restaurants, as if he was just another guy about town, albeit one with strong feelings towards bikes, skateboards and wheeled suitcases.

Four years into owning a dog in Glasgow, I’d become thoroughly complacent about the city as a mecca for the dog-daft. A brief trip to London with him confirmed my fear that the capital was a relative hellscape for canines: scowled at on trains, shouted at by a cyclist, impossible to carry on Tube escalators and not the conversation-starter that a dog can be just crossing the road in Glasgow.

Which was why sitting in Mono on a grey November day last year, drinking a cup of coffee, I did not expect a reckoning. My dog had seen something outside that he didn't like. A growl came from under the table: grrrrrrrr. A few people lifted their heads up from bowls of soup to look around. Grrrrrrr. A courier bike rushed past outside – Woof! Woof! Woof! – and a family scurried past our table. WOOF!!

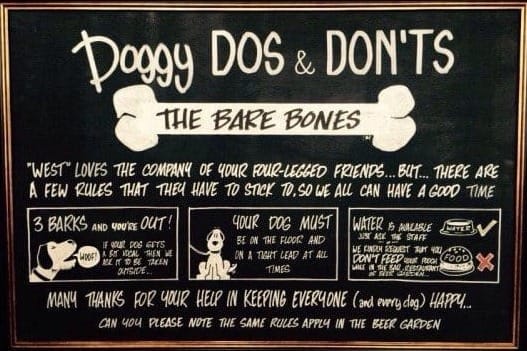

I was already cringing and worrying. And I was right to. A waitress came over and asked me – or rather me and the mutt – to leave the premises. “Sorry, but it’s three barks and you’re out”, she said.

It’s usually indulgence that greets a dog in Glasgow rather than the stricter end of common sense. I left the cafe feeling ashamed for both of us.

On balance, we deserved it, although thankfully we haven’t been kicked out of anywhere since. When I call this month to check if the policy is still in place, a barman at Mono, Seth, explains that an “incident” a couple of years ago with a dog who was “a wee bit overstimulated” caused the venue to realise “not everyone is so into the dog-friendly thing”. He says the “three barks” rule isn’t strictly counted, and it’s rarely enforced. (Ouch.) But it’s in keeping with the fact that Glasgow experimented with dog-friendliness, and is now stepping back a paw or two. Ikea and Silverburn Shopping Centre both trialled access for dogs, and then reversed it.

Meanwhile, an age-old rivalry might be about to be revived. Seth at Mono says the cafe gets multiple dogs a day, but they’ve also had “the odd cat recently. Someone moved into a flat in town and they have a patient cat with a wee basket.”

Does he think dogs are good for business? “People seem to really enjoy it,” he says. “It’s nice to bring your dog along.”

Thanks for reading Natalie's article. If you want more like it, you can sign up to The Bell for free. That'll get you our Monday briefings, stacked with local, original news, reviews and recommendations, and dates for your diary. And you'll get more great weekend reads like this one.