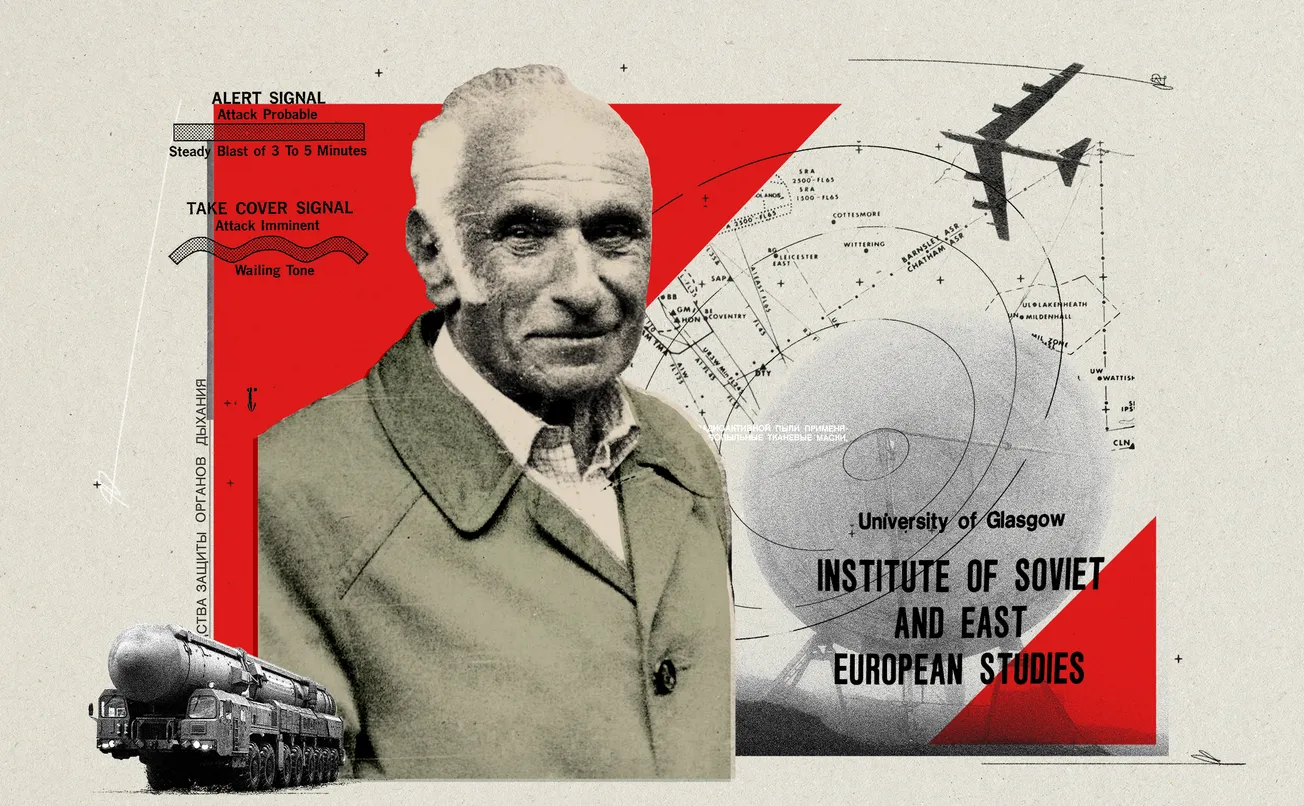

“If we don't protect [Mackintosh’s buildings], we will lose them forever and the city has to wake up to that.” The words of Stuart Robertson, executive director of the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society, spoken to the BBC in 2023.

Robertson also happens to be the man who has ignored multiple requests for comment, clarification and explanation from The Bell over the past three months as to why the society is yet to install any fire suppression system at the Mackintosh-designed Queen’s Cross Church, home of the Mackintosh Society since 1977. For over two years under Robertson’s leadership, the society has sat on a document which deemed the lack of any fire suppression system at the category A-listed building of the highest possible risk.

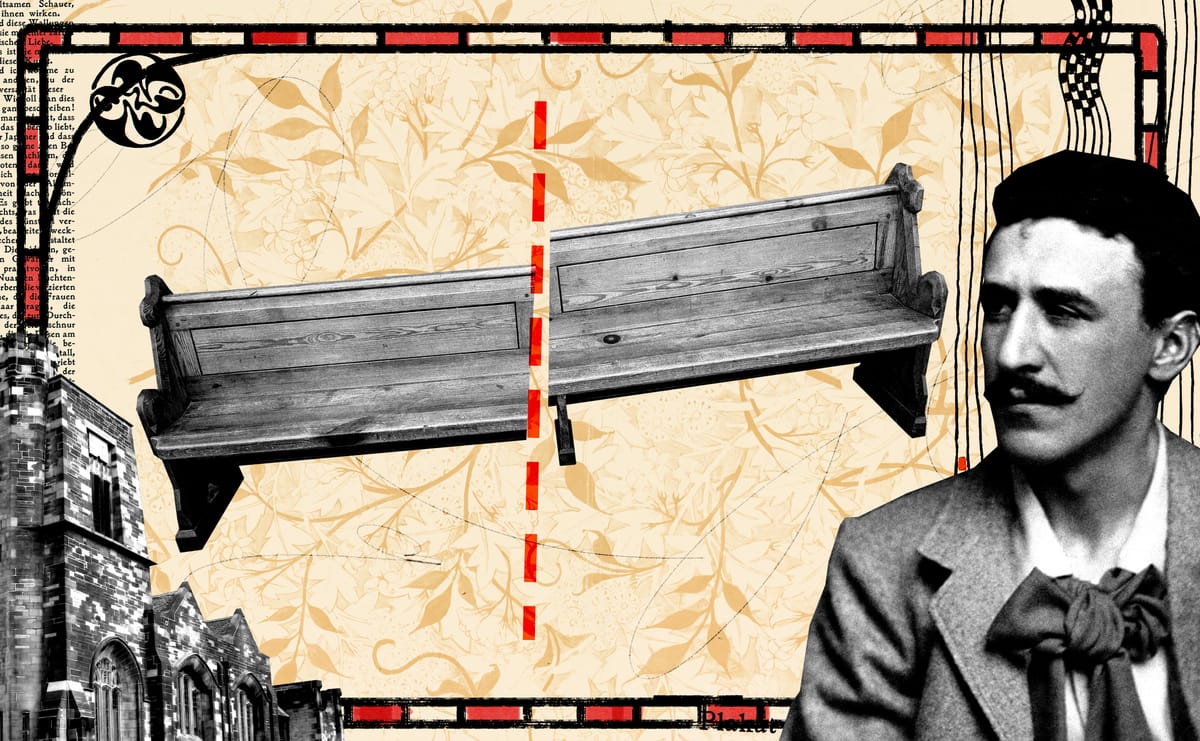

When we first heard these allegations about a lack of fire safety at Queen’s Cross Church earlier this year, we had other things on our mind. It was mid-April, and the 52 year-old Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society was tearing itself to pieces over a pair of pews which had been sawn up and removed from Mackintosh’s only church on Garscube Road.

Nonetheless, we pinged off an email to Robertson. We asked if he could confirm if work was being carried out on a fire suppression system in Queen’s Cross, or if it had already been put in place. We received no response, suggesting there may be something to the allegation that the church had no suppression system whatsoever. After all, if one had been installed, why wouldn’t its director simply say so?

Meanwhile, the pews news continued to brew, with Robertson — who has been in post since 2001 — becoming increasingly beleaguered. His position was already precarious when an investigation by council enforcement officers found that the society’s actions had violated planning conditions by permitting pews of “considerable architectural significance” to be sawn up and sold on Facebook. Besides, we’d shown that both Robertson and the society’s chairman directly contradicted themselves in our own reporting on the pews stooshie.

By the time the AGM rolled around in June, Robertson announced he would be stepping down, staying on in post until February to give time to appoint a successor. At the time, Robertson said his decision to stand down was unconnected with the pews debacle. The timeline strongly suggests otherwise.

Welcome to The Bell. We’re Glasgow’s new quality newspaper, delivered via email. Join our free mailing list to get two full editions a week: a Monday briefing, full of things to do and bitesize news, straight from the city's streets, and a weekend feature.

To get total access to all four of our weekly editions, you can join up as a paying member. We’d love that. But we understand you might want to try before you buy, so click below to sign up for totally free and start getting our special brand of local journalism straight to your inbox today.

Then, towards the end of June, we received an email containing a fire suppression report that had been conducted for Queen’s Cross from August 2022. It provided an overview of the different types of suppression systems that could potentially serve — and save — the Mackintosh Church in the event of a fire. The report concluded that a low pressure misting system would protect all the rooms, bring a “low/medium” water damage risk to fabric and would cost £66,000 to install. A look at the Mackintosh Society’s accounts on Companies House showed they had in excess of £2m in funds in the year ending December 1 2023.

Through investigation and enquiry, we have come to the conclusion that the Mackintosh Society, under Robertson’s leadership, has sat on this report for almost three years — despite members having deemed the lack of a suppression system at the church a high risk to the building.

We’ve established that there is no suppression system active or in construction at the Mackintosh Church. This is despite a 2023 summary of the report being presented to the AGM that June which recommended the installation of a system as a matter of the highest priority and risk level. The next steps for the project were to “procure and install [the] system”. We have tried on multiple occasions to extract an adequate response from Robertson on why this work wasn’t undertaken, but have been met with silence.

It is worth noting that there isn’t a legal requirement for the society to install a fire suppression system. Public buildings such as Queen’s Cross are required to have fire detection, alarm and protection measures in place. Indeed, suppression systems are considered an ‘over and above’ measure in non-residential buildings. However, the occurrence of not one but two fires at the Mackintosh-designed School of Art must surely underline the importance of such suppression systems, especially given the preciousness and importance of the fabric of Queen’s Cross. These include original Mackintosh furniture, artefacts and interiors. In addition to this, there are obvious safety issues: Queen’s Cross sits in the middle of a densely populated urban area, separated from tenements on Garscube Road by mere metres.

Attention has been drawn to the urgent need for a suppression system by various former board members of the Mackintosh Society. Concerns have been raised about Queen's Cross being extremely vulnerable to fire, especially given the building lies empty four days a week. In her 2020 thesis, built heritage professional Dr Rachael Purse highlighted the high prevalence of flammable timber in the church while noting, like the School of Art, it lacked a fire suppression system. Additionally Clare Henry, one of Scotland’s most respected art critics, also confirmed to The Bell that concerns were raised to the society “many times”, and that the situation is “dreadful”.

Over the course of our reporting, we have made various attempts to contact Robertson. He ignored not only our first email in April, but also two subsequent emails in recent weeks, as well as a follow-up text message. Stonewalled, we eventually decided to turn up at Queen’s Cross last Friday. We rang the doorbell, and asked to speak to the executive director in person. We were duly buzzed in, where Robertson seemed shocked at our interest in the story despite our multiple attempts to contact him. When asked about the 2022 report, Robertson told us it was a “very early investigation”, and that installing a suppression system was “not straightforward”.

We asked if any temporary systems had been installed, ones that cost considerably less money and wouldn’t require planning permission, such as placing gas canisters under floorboards (which can cool fire, reduce oxygen and disrupt the chemical reactions that sustain combustion). This same inert gas system was mentioned in the 2022 report as posing “low/zero” risk to the original Mackintosh furnishings and would be more or less invisible to the public. Robertson again said that installing such systems was “not an easy thing” when you’ve got “a big void like this”, gesturing towards the nave, which contains original beams, and the main hall with its Mackintosh-designed panelling, cantilevered galleries and altar table. Many of these features are judged to be of “outstanding significance” in the Mackintosh Society’s own conservation statement, dated 2005.

Robertson referenced other historic buildings, claiming that “few” have a suppression system in place due to the difficulties involved in installation. For Stephen Mackenzie, an independent fire security consultant who gave evidence to the Scottish Parliament about the Glasgow School of Art fires, this isn’t a sufficient excuse. He cited Newhailes, an Enlightenment-era house on Edinburgh’s outskirts where the National Trust for Scotland embarked on an ambitious conservation project. They installed a sprinkler system that was specially designed to accommodate the 1686 mansion's “fragile interior”. But most telling is the final sentence in a summary of the project by surveyor and architect firm GLM: “All involved in the project are agreed on one thing: if it can be done here, it can be done anywhere.”

Robertson brought up the first Glasgow School of Art fire in 2014, claiming that “the water [which extinguished the fire] caused more damage” than the fire itself in parts of the building, such as the lecture theatre. We have to point out here that there was no misting or suppression system in place at the time of the 2014 fire at the Mack. Damage was caused not by a suppression system but the water used by firefighters to put out the blaze. Indeed, a misting system was weeks away from being installed at the time of the 2014 fire. Another was in the process of being installed, but not yet complete, at the time of the 2018 fire. Throughout our conversation, Robertson seemed perplexed as to why we were pursuing the story, even while he himself brought up the two fires which ravaged the School of Art.

Mackenzie describes as “nonsense” the notion that the risk of water damage from a good fire suppression system would outweigh the benefits of protecting the building itself. He compares the amount of water used by the fire brigade when attending an incident to a traditional sprinkler system. The latter will typically use well under a tenth the amount of water to initially suppress a fire than the former, while misting systems like the one recommended in the report use less water still.

It’s also worth noting that, while fires have the potential to damage built heritage (and the benefits of installing a suppression system are weighed against the impacts on the heritage itself), fire also poses a serious risk to life — which should be the primary concern of any fire safety efforts.

Over the phone last Friday, Peter Trowles, a Mackintosh Society council member since 2019, told The Bell that measures have been taken to install a fire system, although he did not provide any specifics on what these were. He raised concerns about the “intrusive nature” of a fire suppression system in a historic building such as the Mackintosh Church, describing it as a “very complicated situation”. “It’s something the church is looking at and continues to look at it. It’s far from simple,” he added.

Trowles also mentioned the water mist system at the Glasgow School of Art in 2018 as an example of a highly intrusive system. We spoke to someone familiar with the Mack’s system who described it as having been “very carefully designed to minimise damage to the fabric”. The same source also pointed out that it does not make sense to compare ‘damage’ caused by careful workmanship to a catastrophic fire which effectively removed the majority of the building.

In a later email, Trowles explained that the board of trustees at the Mackintosh Society “are continuing to ensure that Queens Cross is made as secure and protected as it possibly can be”. As evidence, he referenced “improved CCTV and security monitoring”. He stated that cost was a “major factor”, but also pointed to “potential damage” that installing the necessary pipework and sprinkler heads would cause to the exposed roof beams in the church. Trowles also pointed to a lack of space for a water tank within the confines of the church, as well as the potential need for larger sprinklers for the nave of the church.

While both Trowles and Robertson raise legitimate reasons as to why certain fire suppression systems might not be suitable for Queen’s Cross, neither has adequately addressed our questions about the specifics of the report, which recommend a low pressure misting system. Have they taken the recommendations in the report to firms who could deliver such a system? Have they run the plans past the council’s planning department to receive guidance on how best to protect the integrity of Mackintosh’s designs? Despite our best efforts to find out, we are none the wiser.

Queen’s Cross is one of the very few Mackintosh buildings in Glasgow open to the public. This is not a given in the city; one need only look at the shrouded School of Art, which stands as a testament to Mackintosh’s squandered legacy and the risks of not having adequate fire mitigation measures in place. Meanwhile, Scotland Street School is currently closed. The Lighthouse, meant to be a centre for architecture and design, has remained shuttered since the pandemic; plans to turn it into a “green tech hub” have been branded a “tragedy” by the Royal Incorporation of Architects Scotland. Martyrs’ School, meanwhile, was recently sold to the Bishops' Conference of Scotland — having once been saved from a demolition order, spurring the Mackintosh Society on to hold its first meeting in 1973.

Recent history shows that Mackintosh’s clutch of buildings are exposed to serious risk; the existence of the Mackintosh Society itself was borne out of the imperilled position of his buildings in the 70s; the threat then was not fire, but the Corporation's wrecking ball. The society’s own conservation statement describes Queen’s Cross as “a fine, intact example of the work of an internationally important Scottish architect”, and “a landmark building in this area of Glasgow”.

The leadership of the organisation created to “promote and preserve” the work of Mackintosh does not appear to be taking the findings of this report seriously, despite Robertson’s claims that he is doing “everything possible to make sure this building is safe”.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.