It’s a Wednesday in August and Martin Vincent is stacking books in boxes. He’s inside the Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA) on Sauchiehall Street in his shop Aye-Aye Books, as he has been, Monday to Friday, for the past 17 years. The dynamic is “weird”, the softly spoken Vincent says because when you enter the CCA’s sleek foyer, everything appears as normal. But the lack of patrons wandering Aye-Aye Books, and climbing the stairs to the gallery’s exhibition rooms hint at what’s really going on.

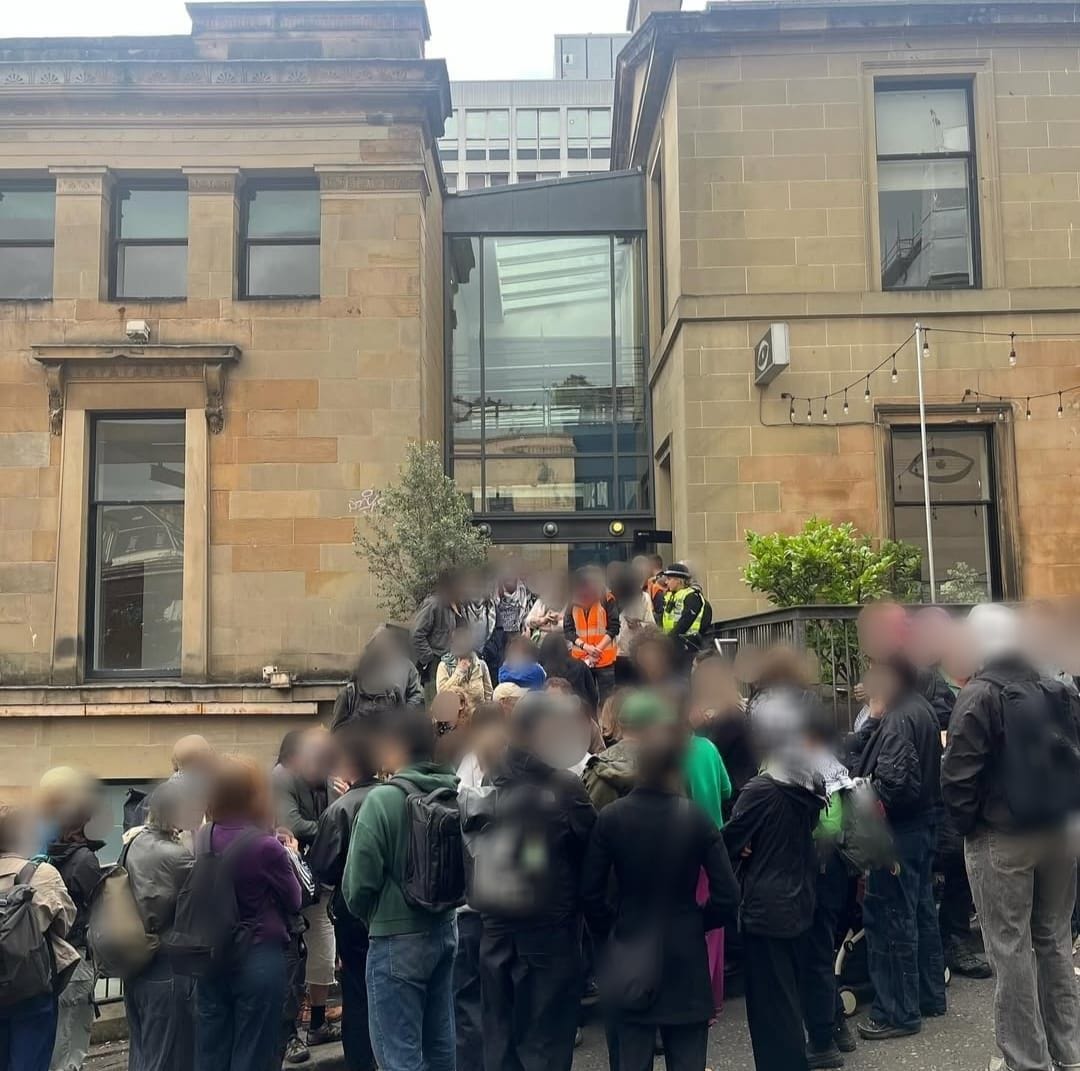

The CCA is still closed to the public, as it has been since 24 June. That day, a group of artists and CCA staff members entered the building to — in their words — kick off a week of events for “resistance, learning, and artistic solidarity with Palestine” in the building’s courtyard. This was organised as a response to the CCA leadership refusing to sign PACBI (the Palestinian campaign for the cultural and academic boycott of Israel). On the day, CCA leaders didn’t allow the so-called ‘Liberated Zone’ to take place, police were called, and a standoff followed which led to the arrest of a protester who reportedly had to receive hospital treatment as a result.

After the fracasse, the CCA announced that, to “prioritise the safety and wellbeing” of staff, and to allow “space for reflection” it would remain closed for the remainder of the week. But it didn’t reopen. Instead, no word on when or in what form it will reopen has been shared, only eviction notices to long-term retail tenants like Martin Vincent, and curt emails to exhibiting artists.

Vincent received his email from Steve Slater, the interim director of operations, on 18 July, after weeks of silence. It informed him that: “this period of closure marks the end of CCA’s relationship with Aye Aye Books [sic]”. He was allowed back into the building three days later to start packing up nearly two decades of residence.

“[We’re] just trying to make the best of a difficult situation,” he says, haltingly. We’re sipping on flat whites at a local cafe. Vincent’s nervousness in speaking to me is palpable.

The immediate “situation” is the cavernous void that has opened up between the CCA’s management and its staff and artistic community. But that’s just part of the story. Although June’s protest was the catalyst for this latest closure, the CCA’s trials began far earlier. From a funding drought to worker revolts, it’s been a tough few years for the CCA and its staff.

Welcome to The Bell. We’re Glasgow's new newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Bell every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

A history of an art institution

The CCA is being flanked by two competing pressures. One side is internal: exhibiting artists, many staffers, and the wider Glasgow art scene. Long simmering grievances have boiled over with the board's refusal to agree to PACBI, and how management handled the recent AWPS protest. There’s a feeling the CCA isn’t the radical progressive space many hoped it would be

The other is very much external: a decade and a half of eroded funding meaning reliance on donations and commercial revenue is more important than ever. But footfall at the CCA is down by over 50% and has been since the pandemic. The chaotic closure of the Saramago cafe in 2023 also impacted the cash coming in. And when we previously covered drama at the CCA, artists and the public alike conveyed a distinct lack of enthusiasm around its current programming.

This wasn’t always the case. Initially opened as the Third Eye Centre in 1974, the art space was the focal point of the city’s counter culture and hosted the likes of Whoopi Goldberg and Allen Ginsberg, Billy Connolly and John Byrne, and Peter Howson and Damien Hirst. Funded by the Scottish Arts Council, it brought contemporary art to the people of Glasgow, from the grassroots. Then, in 1991, The Third Eye Centre closed, leaving space for the CCA to open its first exhibition in 1992. Since then, it has continued to be an arts hub for the city.

Current CCA leadership consists of just three remaining board members: Jean Cameron, Kirsty Ogg, and Paola Pasino. Steve Slater is the acting director of operations. But the AWPS protest claimed some scalps; as of 4 June, there were six other CCA board members who have now stepped back: Andrew Bell, Lesley Davidson, Roddy Hunter, Louise Norris, Natalia Palombo, and Tawona Sithole. I’ve contacted the six to ask why they no longer sit on the board but have had no response.

We first reported on closures at the CCA last year, when the gallery shuttered its doors for four months from December 2024, due to “significant financial uncertainty”. Creative Scotland funding was late being announced — without it, the future of the space looked dire. CCA accounts for the April 2023 to March 2024 period show the organisation had £250,000 less in funds than it did the previous year (£162,000 vs £434,000). While waiting on a decision from Creative Scotland, bosses said they would be restructuring the CCA’s set up.

This April, the CCA reopened, having received a total of £3.39m in funding from Creative Scotland for the next three years. At the time, the CCA posted to its Instagram thanking “everyone who championed us and believed in what we do”, acknowledging that the community’s support is what allowed it to survive and gain the “significant uplift” in funding from Creative Scotland. There was no update on the planned restructure.

And reopening wasn’t the end of the centre’s problems.

“I’d have to think very carefully before showing there again”, says Alia Syed over the phone. The experimental filmmaker, who has had work screened or exhibited in New York’s MoMA as well as galleries in Madrid, London, and New Delhi. This summer, she had a show at the CCA; ‘The Ring in the Fish’, a series of vignettes inspired by St Mungo. “I’ve never been so disrespected in my life”, says Syed, exasperation clear in her soft Glaswegian accent, as she refers to the institution and senior management rather than staff on the ground.

The exhibition was due to open on 17 May. The lead up was disappointing, Syed recounts. Contrary to the usual months-in-advance warning art journalists are usually given, the CCA only put out a press release about her show a week after it started.

The publicity the CCA provided was “terrible”, Syed believes. Attendance was hampered further by the abrupt closure of the CCA midway through The Ring in the Fish’s run, planned until 26 July. Since then, Syed has only received one email from Steve Slater on behalf of the space. Sent three weeks ago, all it said was that the CCA wasn’t planning on rescheduling or reopening her show. No explanation, and as yet, no acknowledgement of what appears to be a breach of contract.

Another artist I interviewed, who recently had work on display in the CCA, painted an almost identical picture of feeling “avoided” by management. They also said they wouldn’t be back to show at the CCA unless there’s new leadership. Like Syed, they’re frustrated with how their show was administered, and disappointed by the response to the PACBI campaign.

How (not) to handle a protest

When it comes to the demonstration that resulted in the CCA’s immediate closure on 24 June, there’s two duelling narratives. Both the CCA and Art Workers for Palestine Scotland (AWPS) who organised the ‘Liberated Zone’, have posted contradicting statements online.

Before the action, pressure for the CCA to sign up to PACBI was growing; on 5 June, 40 members of staff signed a letter asking the CCA to formally align with the accord, which would require the organisation not to engage the services of or provide funding to any Israeli academic or cultural institution due to Israel’s actions in Palestine.

Citing the need for political neutrality and potential legal challenges, the CCA refused to endorse this, despite the workers acknowledging that they are “already upholding this work day to day”. Around 20 of the 251 organisations that received the same Creative Scotland funding have endorsed PACBI, and so have almost 200 Scottish art institutions, according to the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) movement.

As a result, AWPS announced a “spontaneous programme takeover of CCA”. It appears that group believed the CCA would allow, if not welcome the action, without pushback. In an Instagram post announcing the ‘Liberated Zone’ schedule the day before, uploaded by the AWPS account, they wrote: “We look forward to meeting you at our beloved CCA in warmth, solidarity, and belief in what our art institutions can be”.

But on 24 June, a few dozen or so demonstrators walked up to find the doors at the front of the building shut. A sign read “the CCA is closed to the public today”. Some of the group sat outside on the pavement, while others entered the foyer on Scott Street.

Videos and images posted to social media show a small group of protestors appearing to be contained within the foyer by police, with AWPS claiming police were “taking their details”. Another clip captures the moment Lindsey Murray is arrested by police. The footage is striking; Murray is hauled into the back of a police van by her oxters and wrists, while assembled demonstrators shout “shame” and “assault” at officers. Police Scotland have confirmed that a 63 year-old woman was arrested for abusive behaviour, police assault, and resisting arrest, but also that “complaints regarding the incident” have been received, which are being dealt with accordingly.

As the dust settled, many posts from Glasgow’s artistic community appeared on social media in support of AWPS, denouncing the CCA and police Scotland. Security had been instructed by the CCA board to prevent the group gaining access to the building, claim AWPS. They also believe that Steve Slater and the board colluded with Police Scotland in a “premeditated brutalisation” of the CCA’s community. They demanded the resignation in particular of Slater, Roddy Hunter (who now apparently has stepped back), and Jean Cameron, board chair. The ‘Liberated Zone’ was instead established at the Listen Gallery.

The CCA responded to events the next day on Instagram by saying it “underst[ood] the strength of feeling” and that it remains “committed to engaging with this moment thoughtfully”. The organisation has since updated its account of events on its website, saying only after protestors entered the building were police called. It also confirms that it has not called for charges to be pressed against anyone involved and has had “no further contact” with police.

Regaining trust?

A bond has been broken. The “belief” AWPS members, and others in Glasgow’s art scene, had in the CCA as a progressive haven has been challenged. In a statement posted on 2 July, AWPS branded the space the “Centre for Contemporary Apathy”. We are deeply disturbed,” they wrote. “Rather than taking accountability for their actions, CCA’s leadership continues to misrepresent events, discredit organisers, and align itself with a growing culture of state repression”.

Whoever the CCA is aligned with, the organisation is clearly undergoing extensive change. The events of the 24 June, another CCA statement declared, have “accelerated” an already-planned “turnaround” — presumably the long-trailed restructure. It also says that it will only reopen when “safe” to do so. What threat to ‘safety’ the CCA is experiencing is unclear. A spokesperson for Art Workers for Palestine Scotland says they believe “we are moving in the right direction”, in terms of reconciliation with the CCA.

Martin Vincent isn’t feeling so optimistic. On the hunt for new premises, he tells me this period has been characterised by cold bureaucratic communications, on the rare occasions they have been issued, and a lack of transparency. He’s hopeful Aye-Aye Books can succeed again in a new space, and was already considering leaving after the first closure. But he’s clearly hurt by the ordeal — and leaving behind nearly two decades of work and memories.

So what now? It’s a month and a half after the CCA’s latest closure. The only updates I’ve been told are whispered rumours that I can’t verify. In the time I’ve been reporting this story I’ve heard that the board are going to resign; Martin Vincent confides that the bookshop is apparently being turned into (another) cafe; and everyone I’ve spoken to tells me that staff are facing heavy pressure not to speak out. What is apparent, is there’s a culture of silence surrounding the CCA. As in December 2024, staff don’t want to talk. Management won’t either. It’s a black box. A spokesperson for the CCA did tell me that on Friday 8 August there was an all staff meeting, that the CCA is "reviewing its public messaging to further reflect staff voice", and that next week there will be further details that can be shared. So for now, I'm still in the dark.

For Alia Syed, the CCA has “totally failed in its remit” to its community and to artists. She says following 24 June, management just “put their walls up” and didn’t attempt any “form of reconciliation or explanation” for those affected.

It’s not hard to see the irony here. The CCA has traded on a reputation for the radical and “civic-led”. Its exhibitions aim to “unravel the web of legacies left by the colonial project”. But for years, competing demands have been forcing a painful reckoning. Now protestors are locked out and Martin Vincent’s books, bearing titles like Become Ungovernable, are being packed away.

“It will be hard to regain the trust” of those involved in the politics and the protest, says Vincent. While the ground staff he’s encountered in CCA while packing up his shop have been “incredibly supportive”, he feels the “top down” nature of the centre is its Achilles heel, at odds with their stated ethos and aims. The CCA claims to be a “platform for a collaborative, civic-led programme” but right now it’s nothing, to no people. Vincent, who pitched up at the CCA in 2007 as part of a temporary exhibition but stayed ever since, believes the people of Glasgow own the CCA, not the board or management.

In a time where public spaces are being starved of resources, this may be proving too difficult an ideal to live up to alongside a drive for improved commercial performance. In the meantime, all that those who’ve invested their time, money and creativity into the CCA can look to for answers is a few statements on the organisation's websites. One of them promises that the CCA is “engaging with… key stakeholders” during this “time of reflection”. “I guess somehow we’re not stakeholders or part of the community”, Vincent says, sadly.

*article edited 11.08.25 to remove reference to a lack of apology from the CCA to Alia Syed. Steve Slater apologised via email.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.