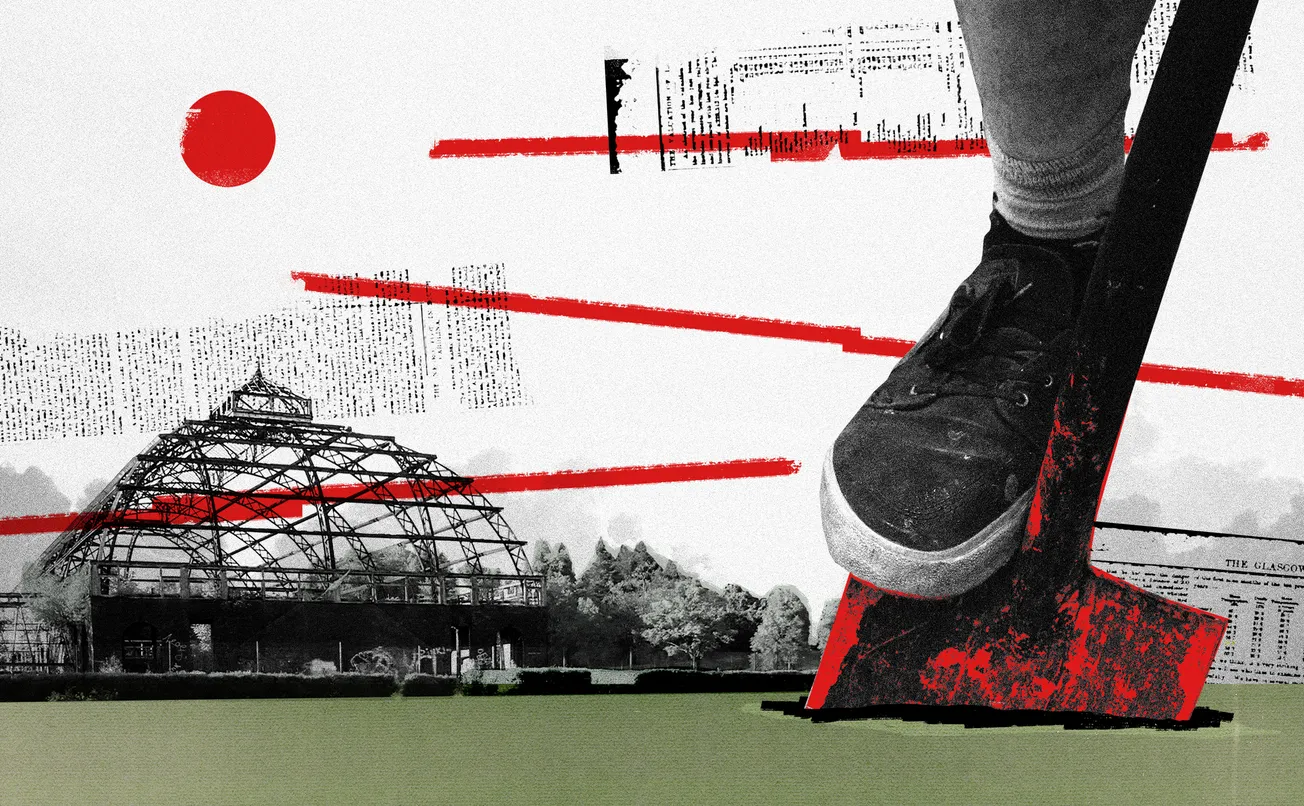

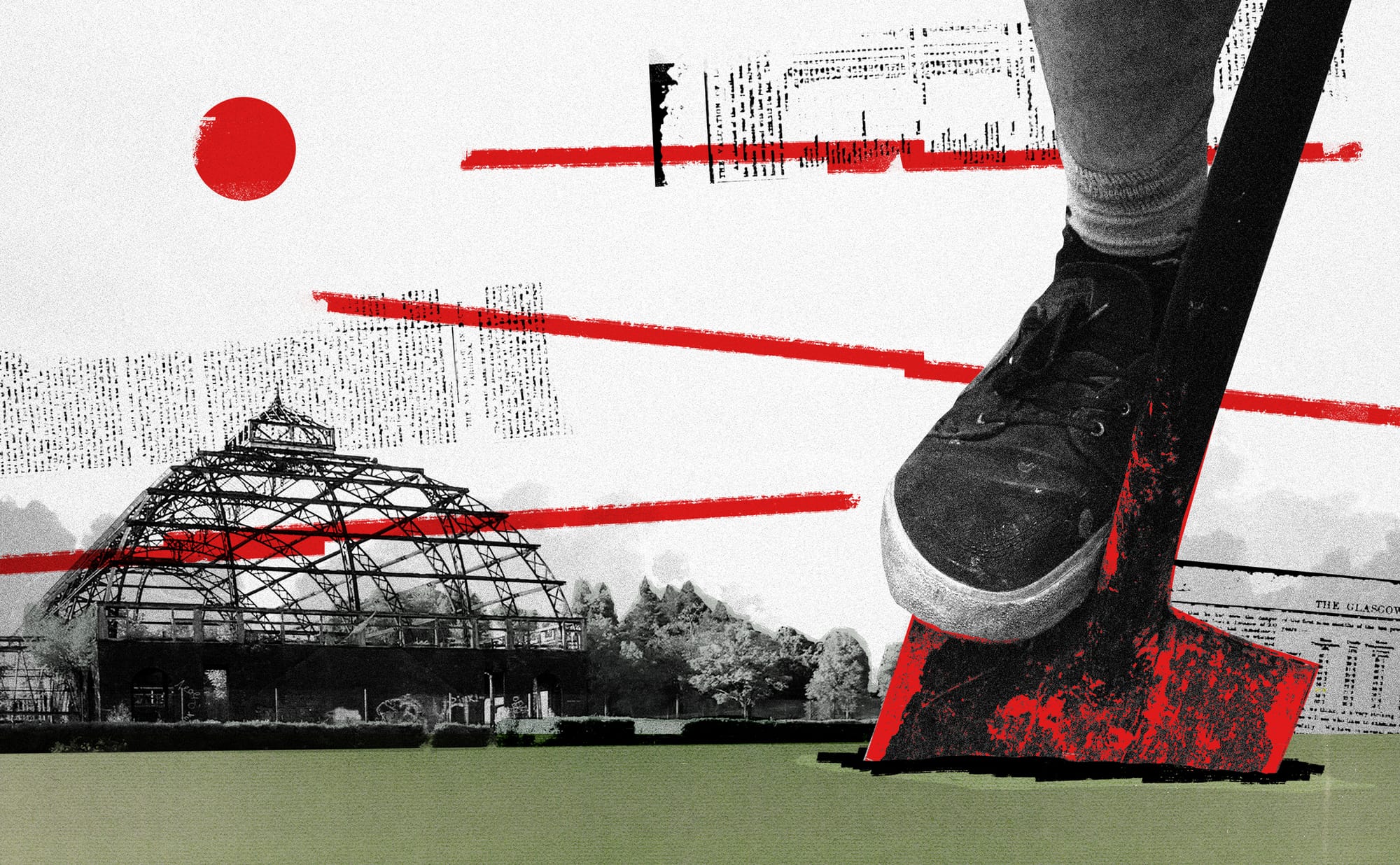

From its vantage point high above Glasgow, Springburn Park was once a showcase of Victorian splendour. The intricate bandstand bequeathed by local locomotive magnate James Reid in 1892 is long gone though, and the spectacular winter gardens his son provided funding for have lain in ruins for 40 years. With mature trees and sweeping paths, the area’s natural beauty remains, but practically everything else, from its bowling greens to cricket pitch, lies overgrown and abandoned. No wonder local people felt so attached to the park’s synthetic football pitch, one of the only facilities still in regular use.

But then came Covid-19. For a year, everything shut down, until February 2021, when the Scottish Government started handing freedoms back to its citizens, opening up schools and allowing sporting activities to start again. In Glasgow there was just one problem: sports facilities, once closed, were proving too expensive to reopen. So the local authority came up with a plan.

The People Make Glasgow Communities (PMGC) initiative, announced on 25 February 2021, was ambitiously framed as a “call to action”. Glasgow City Council asked people who “know, use and are passionate about their local resources” to take on more responsibility for them, allowing “more control” over the “important decisions that affect their lives”. “Current best practice,” then–deputy council leader, David McDonald, said at the time, “shows community services which are locally managed and delivered are the most successful in meeting community needs.”

Four years on, things haven’t really worked out that way in Springburn Park. While in the course of reporting another story on the space last year, I kept hearing tell of a dispute simmering behind the scenes. A beloved local trust had been beaten out for use of the pitch by an outside organisation, who swiftly went about altering access to the one major facility still in operation at the park. A mercurial former SNP councillor presided over the new challenger. Springburn residents were up in arms. I had to find out more.

The takeover

Partick Thistle Charitable Trust (PTCT) is an independent charity that uses the Championship side’s name to raise cash for football-based programmes in the north of the city. The trust took over Springburn’s pitch in September 2020, as part of a pilot scheme run by the council’s culture and leisure arm, Glasgow Life. Run by local footballing legend Paul Kelly, who played for Alloa Athletic and latterly managed Royston Road side St Roch’s, PTCT used the pitch to host community events as well as training sessions for local teams. When Kelly died in November 2021 his loss was keenly felt.

So when PTCT applied to run the pitch under the PMGC scheme, many within the charity assumed they would get to continue the good work begun under Kelly. No one expected to lose out to another charity, and yet that is exactly what happened. Brunswick Community Development Trust, whose activities up to that point had been focused on neighbouring Balornock and Barmulloch, was awarded the PMGC contract instead. It has not gone down well in Springburn.

Audrey Dempsey is a local councillor for the Springburn and Robroyston ward. The sister of Paul Kelly, she also knows the Springburn pitch well. Known for her (sometimes controversial) outspokeness, she is typically blunt when she tells me that much of the animosity is aimed at Greg Lennon, Brunswick CEO and colourful North Lanarkshire councillor, who quit the SNP two years ago, to co-launch break-away party, Progressive Change North Lanarkshire. Dempsey says constituents complain to her that Lennon is difficult to deal with and appears to give priority to teams from outside the immediate area. Local teams feel locked out of what was a publicly owned asset as a result.

One footballer, whose team has played at the Springburn pitch for years, says booking slots — something that was standardised across city facilities when Glasgow Life was at the helm — has become “a farce”. “No local clubs can get lets,” he says, asking not to be named. “We don’t waste our time any more.” Officials at both Athena Glasgow Women and Girls Football Academy and Ashfield Juniors Football Club and Youth Academy have repeatedly made the same complaint, saying they have been sidelined in favour of Brunswick’s own academy teams. Instead, they say they are being offered slots that are either too early for coaches to make from their day jobs, or are too late for younger children to attend.

Welcome to The Bell. We’re Glasgow's new newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Bell every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

Brunswick has declined to put Lennon up for an interview, saying he is an employee rather than the “face” of the organisation and can neither speak to, nor be held accountable for, collective board-level decisions. Still, questioning his integrity, Brunswick chair Zoe Buchanan says, questions the integrity of the entire organisation, something that is “serious and potentially damaging”.

Brunswick has, she claims, “reopened and revitalised” a facility that was at risk of closure, introduced free community sessions and partnered with local schools to help increase access. Buchanan would be disappointed, she warns, if “a mischaracterisation of individual staff resulted in unnecessary reputational harm”. In any case, Companies House filings show Brunswick is funded by organisations including Glasgow City Council, the National Lottery Community Fund, and Cash for Kinds, meaning it should go through numerous separate integrity tests on an annual basis.

But the antipathy towards the organisation is perhaps understandable when put in the context of the relative ease with which it has been able to take over the Springburn facility. The trust was initially given permission to use the 3.2 acre site, which includes an 11-a-side synthetic pitch, changing facilities, toilets and an office space, for a 12-month probationary period before a 25-year peppercorn lease was granted in June last year. Buchanan says the PMGC application process “requires organisations to have clear operational planning, compliance procedures and financial oversight” but that it is nevertheless “self-explanatory and well structured”.

Brunswick is also under fire after withdrawing financial support for its own academy’s 2017 team. The trust says its hand was forced because some of the team’s parent coaches were not registered with Disclosure Scotland’s Protecting Vulnerable Groups (PVG) scheme, something the Scottish Football Association requires of all grassroots teams. It also stresses it has been carrying the 2017 group financially for some time, something it is no longer prepared to do. It has not gone down well with the parents involved, though, who claim they have applied for PVG clearance and dispute Brunswick’s analysis of the finances. In an email to Lennon, one parent notes that the 2017 team's coaches have shown "outstanding commitment to the development of the children", something she says he would have noticed if he'd "spent any real time involved".

Waiting games

Paul Maxwell is both chairman of West of Scotland League side Ashfield FC and managing director of the club’s academy, which offers training opportunities to 200 children across 10 different age groups. Over a long telephone call, and several lengthy email and text conversations, his passion for both the sport and the local area shine through. Maxwell has used the Springburn pitches for some Ashfield training sessions, he tells me but is currently locked in dispute with Brunswick over damage Lennon claims his players have done to the facility’s toilets.

Maxwell has engaged with Brunswick’s investigation into the claim but, with feelings running high, fears it is being used as a means of blocking Ashfield from further using the site. Two of the academy’s teams have, he says, so far been left unable to book training slots for the season ahead.

Feeling the club has been blocked from Springburn is frustrating enough, Maxwell says, given it has played there unhindered for several years. What makes matters worse is that Ashfield made a joint application to run the nearby Chirnsyde playing fields in Milton in 2021 under the PMGC scheme. That application is still sitting with the council, four years later. Ashfield is not alone. I sense an underlying resentment that Brunswick’s Springburn lease was waved through so quickly.

“I’m in the fourth year of the official process for Milton,” Maxwell notes, adding that Ashfield will need to raise up to £3m to install a stand, lighting, changing facilities and security if their application for the site is successful. Having grown up in Milton, he says the local area, one of the country’s most impoverished according to the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation, “has nothing”.

Being able to bring a state-of-the-art football facility that engages local children to the area is, “first and foremost about giving something to the community”. While that chimes with what PMGC was set up to achieve, Maxwell says the delay has been “70% on Glasgow City Council’s side and 30% on ours”, but he has struggled to line up funding, in part because of the slow process of the PMGC application.

Since launching its call to action at the beginning of 2021, the council has received over 800 expressions of interest in PMCG, a significant portion of which relate to Glasgow Life sporting facilities (the scheme also covers libraries, parks and heritage assets). The vast majority of those enquiries did not make it past the initial assessment stage but, for 150 that did, progress on taking them forward has been painfully slow. Just 12 assets have been handed over while a further 12 are currently “in development”, while the team responsible for handling PMGC applications has dropped from eight people when it was set up to four now.

Additionally, of the 12 that have been handed over, the decisions on at least two have caused outcry in their localities — in Cathkin Park, the war over the football pitch is so bad, it made it to Scotland’s highest civil court.

A council spokesman says timescales are affected by a range of different factors and notes that, because many of the organisations looking to take over council facilities are run on a voluntary basis, they have “different levels of capacity” for engaging with the process. Agreeing leases on properties that are in varying states of repair can also be tricky; with no dedicated advisers allocated to the PMGC team it can, the spokesman adds, take months for those leases to be drawn up, the whole process “impacted by the workload of the council legal services team”.

For councillor Ruairi Kelly, who has oversight of PMGC through his role as convener for housing, development, built heritage and land use, the scheme has been a victim of its own success. Dreamt up in response to Covid and made possible thanks to the 2015 Community Empowerment (Scotland), it is, he says, “something there is no precedent for in other local authorities across the country”. As a result the council had no idea about how many applications it was likely to get; the initial deluge came as a surprise.

But PMGC is also a victim of the fact that, pre-pandemic, the council had allowed many of its assets to become dilapidated. The scheme is taking time to facilitate because the council has to make sure it is not just transferring liabilities to community organisations, Kelly says. “We don’t want to drop that in the lap of an organisation that doesn’t have the finances to deal with it.”

Ultimately, it has been a steeper learning curve than the council had anticipated, with every application “throwing up something new”. “Overall it’s been very popular and well received,” Kelly says. The main area of contention is not that the programme itself is bad, he adds, but that “applications can’t be dealt with in the timeframes people would like”.

When the council launched PMCG, McDonald, who did not stand for re-election in 2022, said it would “give people a stake” in local services and create “an opportunity for us all to be involved in making our communities stronger and better for everyone”. Four years on, the scheme has undoubtedly given certain people a stake. As for the rest of the aims, well. The jury's out.