Hector Smith would have turned 27 in 1975. Born in Jamaica when it was still a British colony, he had emigrated to the UK as a teenager and married a Glaswegian woman, Ann, in his early 20s. But his life was cut short on a Friday afternoon at the beginning of February that year, on one of the tenemented avenues off Woodlands Road — the very quiet streets that had long been popular with recent arrivals in the city. Ann answered the door of their first-floor flat to men intent on a violent confrontation. They said they were raising money for the paramilitary Ulster Defence Association. One of the men, Brian Hosie, was a member of the National Front.

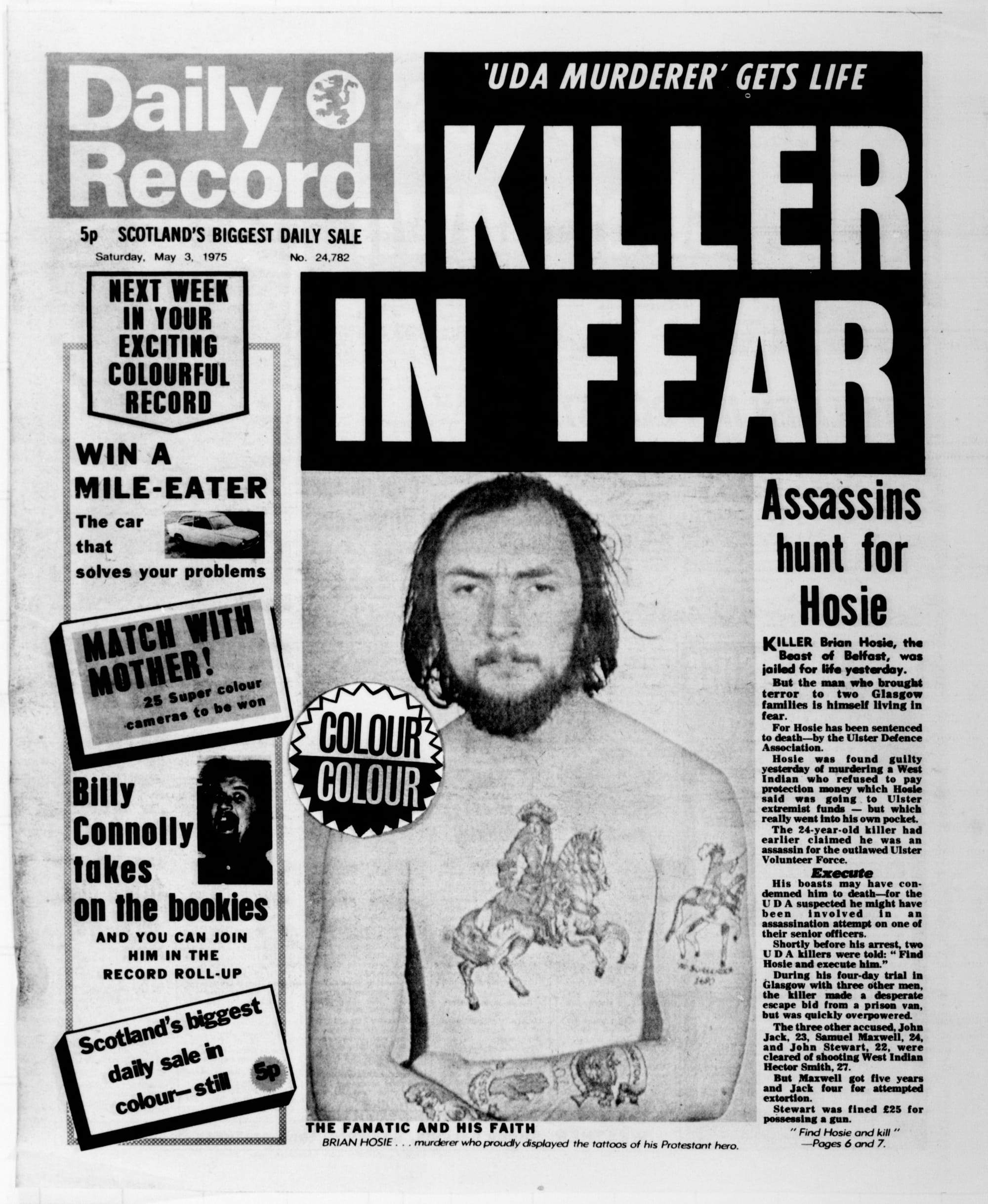

Sentenced to prison for an armed robbery he committed as a teenager, Hosie had spent the first half of the 1970s watching from his cell as the conflict in Northern Ireland grew from the protests and civil disorder of the late 1960s into a sustained, bloody war in which hundreds were dying each year. He wanted some of the action for himself, and within days of getting out of jail in mid-1974 he was on the ferry across the Irish Sea, seeking to make his name with Northern Ireland’s nascent loyalist armed groups. He already had the tattoos to show for it, with garish imprints of King William of Orange and the Red Hand of Ulster emblazoned across his chest and arms.

But making it in the cut-throat world of loyalist paramilitaries required more than just the right tattoos and a capacity for violence. It meant an ability to follow orders and a level of tact and guile that the 24 year old Hosie, who had spent his youth stumbling from approved school to borstal and eventually prison, did not come close to possessing. After months of attempting to ingratiate himself with the UDA, they had told him his services would not be required. With nowhere else to go, he returned to his family home in Glasgow in the last days of January 1975.

Hosie was dejected, but it was not in his nature to lie low. In the mornings, he would make his way through the city to a reputed hangout for loyalist paramilitaries and their supporters: the Bristol Bar on Duke Street. To this day, it is a pub that has an outsized reputation in Glasgow — and beyond — as a staunchly defiant Rangers bar, unmistakably clad in red, white and blue.

It was here, on a Friday morning in February 1975, that Hosie was holding court, freely boasting to anyone who would listen of his involvement in shootings and other nefarious activities in Northern Ireland. There was little reason for anyone to doubt him. It would later be said of Hosie: “That’s all his head’s full of — bangs and bombs. He thought of nothing else. It was his scene.”

Hosie needed money, and he had a plan. He would get a gang together and they would extort money from prostitutes working in flats across the city. He knew of some, and it wouldn’t take much to extract the names and locations of other women ‘on the game’ once they’d got started. The funds would all be going to the UDA, of course. This was both suitably threatening, raising the spectre of an army of dangerous paramilitaries lying behind Hosie’s grimace, and also impossible for anyone to verify. Alongside his claimed UDA affiliation, Hosie was also carrying around a membership letter of acceptance from the National Front, the far-right political party which was in a period of ascendancy after a series of positive election results in England. Also inside his pocket, wrapped in a handkerchief, was a loaded revolver.

The pub closed at 2.30pm, by which point Hosie had managed to rope three other men into his plan. They headed to the west of the city, trying various addresses around the Woodside area. The first two were unoccupied, but they struck lucky at the third: it was answered by a woman, Jean Kennedy*, who one of the men was friendly with. Hosie told her that they wanted to speak with her husband, Raymond*, and needed £10 a week for the UDA from him. If they paid up, they would “get security”. If they did not, they would be shot.

The couple did not have £10 in the house. It was a decent amount, being about a full day’s pay for a manual worker. Raymond soon arrived back at the house, but they could not stump up the cash. Instead, the men told the couple to take them to other addresses where they could continue to build up their protection racket. The four men and the two terrified hostages all crammed into the Kennedys’ car.

A murder in Woodlands

Hector Smith was a father of three and lived with his family in a flat on Arlington Street. Despite largescale migration from the Caribbean to Britain during the 1950s and 1960, few among what became known as the Windrush Generation had settled in Scotland. Woodlands was, however, among the most ethnically diverse areas in the city, being where many South Asians had settled in preceding decades. It was also an area suffering from decades of neglect, with crumbling tenements and, recently, the imposition of the vast Charing Cross motorway interchange to its eastern flank.

It was to Arlington Street that the car headed. Four men made their way up the stairs of the tenement close and launched themselves into the Smith’s flat. Hosie did not waste any time in setting out his terms to Hector, taking out the gun and yelling at him: “We are the UDA. We want £10 a week from you.”

But Hector stood his ground. He told Hosie that he wouldn’t be threatened by him and that he wasn’t going to pay up. At that, Hosie lost patience, and amid a torrent of racist abuse, he grabbed Hector’s throat with one hand and threatened to hit him with the other, which was still clutching the revolver. The gun was fired at point-blank range and Hector staggered backwards.

Ann had taken the three children into a bedroom and closed the door firmly behind her. She waited until she heard footsteps heading away, before quietly emerging with her oldest daughter. Hector — her partner of nine years, her husband of five, and the father of the three petrified children in the flat — was lying in a corner of the living room. The police and ambulance arrived quickly, but they could not save him.

The gang piled back into the car and fled through the darkness of a February evening. The Kennedys were in a state of total terror, but the others were in high spirits. Hosie smirked as he got into the vehicle. “That’s him shot. I shot him through the head. That’s one less black man to feed in this country.”

Some of the group returned to the Bristol Bar, while others disappeared to a house in Baillieston. The gang — now bound together by a brutal murder — talked incessantly of the UDA, clearly hoping that paramilitary backing (whether real or imagined) would lend the whole grubby, tragic affair a legitimacy and sense of threat that would keep the witnesses’ mouths firmly shut. At one stage, Hosie told Jean that they were going to “vote her in as a member” of the organisation, and said that they would escape to Ulster in a fishing boat, where he knew people who would hide them.

Sorry to interrupt. We hope you're enjoying this article. As one of over 22,000 free readers we just wanted to give you a heads up about our summer offer. Right now, you can get a fully-fledged Bell membership for just £1 a week for the first three months.

That's a 50% discount on our richly-reported narrative journalism. This old school, boots-on-the-ground work takes time and money. We've already got over 600 people backing us with their cash. Now you can too, for less than the price of two coffees. Grab it before the end of May.

They ended up at one of the men’s houses in Garthamlock, a post-war housing scheme in the northeast of Glasgow. Jean suggested they could keep the night going if they headed back to the west of the city. She knew there was a dance organised a couple of streets away from her house that night, and it had a late licence. Heading back to familiar surroundings seemed a safer bet than flitting between UDA safe houses, drinking dens or whatever else Hosie had planned.

The party was being held at the Woodside Halls, the austere brick-built municipal hall that has sat in the middle of the Woodside area for the last century. Yet, unusually for the time, it was a gay disco. Eight years after decriminalisation in England, homosexual acts between men were still illegal in Scotland, and would remain so for another six. Despite this, Glasgow Corporation had recently begun allowing hall hires and alcohol licences for dances organised by the Scottish Minorities Group, the country’s first gay rights organisation that had emerged just a few years earlier. The earliest of these were held at Woodside and Partick Burgh Halls.

Hosie and another of the men took up the offer, apparently keen on avenues for further drinking, which even on a Friday were hard to come by after 10pm. It was a bold move, not least given the hall’s proximity to the scene of that afternoon’s murder, which sat just a few streets away. The area would be crawling with cops. Furthermore, Raymond Kennedy was known to Ann and it was highly likely that the police were searching for him, and on the lookout for the car they were travelling in.

Arriving at the hall, the couple spied an opportunity to escape. While Hosie briefly disappeared to the bar, the other man indicated to them that this was their chance to slip out. It was around 10.45pm when the frantic couple got to Maryhill police station. The officers there had spent all night trying to trace Raymond and were surprised when he, quite literally, fell into their arms.

The police immediately raided the Woodside Halls. With the lights on, music off and exits barred, they had a room full of besuited, bearded men to contend with, and a murderer in their midst. There was only one thing for it: all of the attendees were told to line up, remove their jackets, roll up their sleeves and have their arms inspected for signs of a prominent tattoo of King William III. But Hosie had already left, and the upper arm audit of Glasgow’s homosexual underground failed to turn up any sign of King Billy.

The next stop for the CID detectives was the Bristol Bar, which was scoured for any sign of the murder weapon. The search was negative but by this point they had a clear idea of who they were looking for.

A forgotten victim

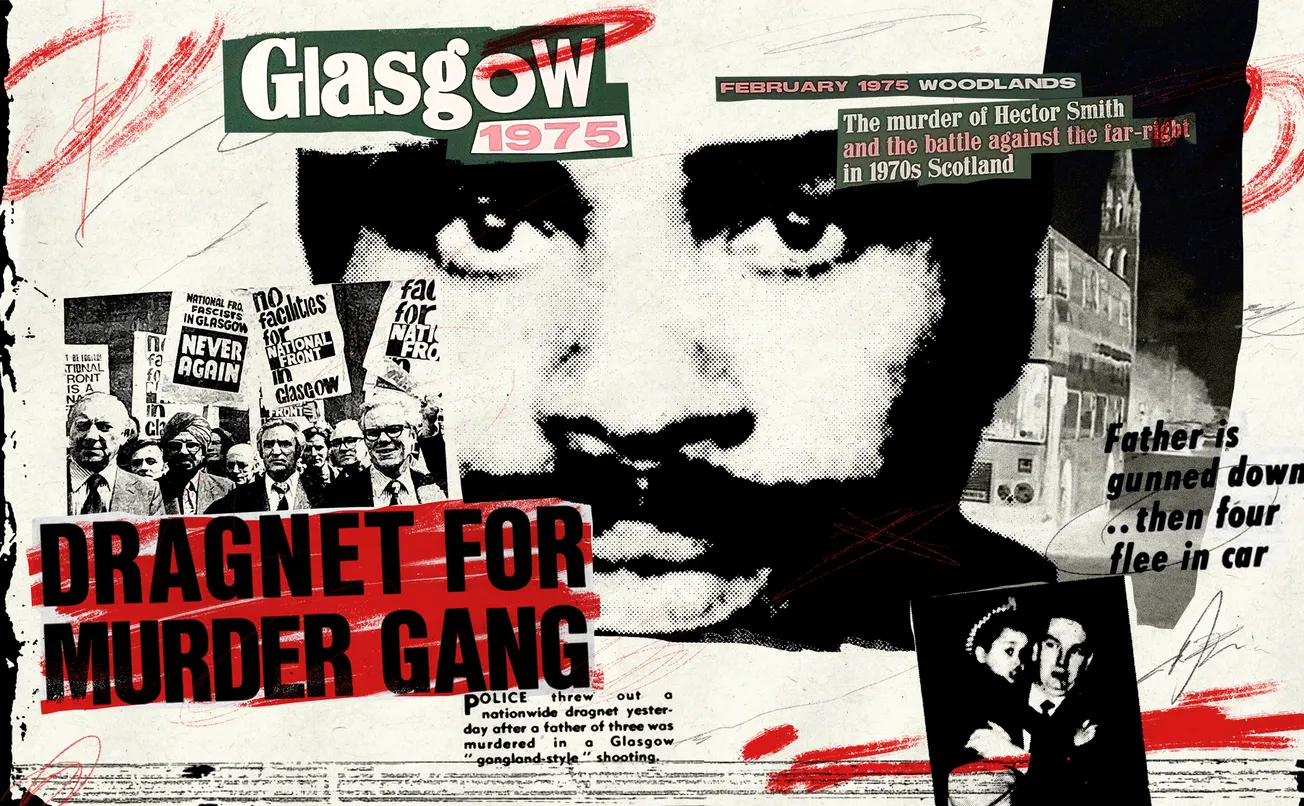

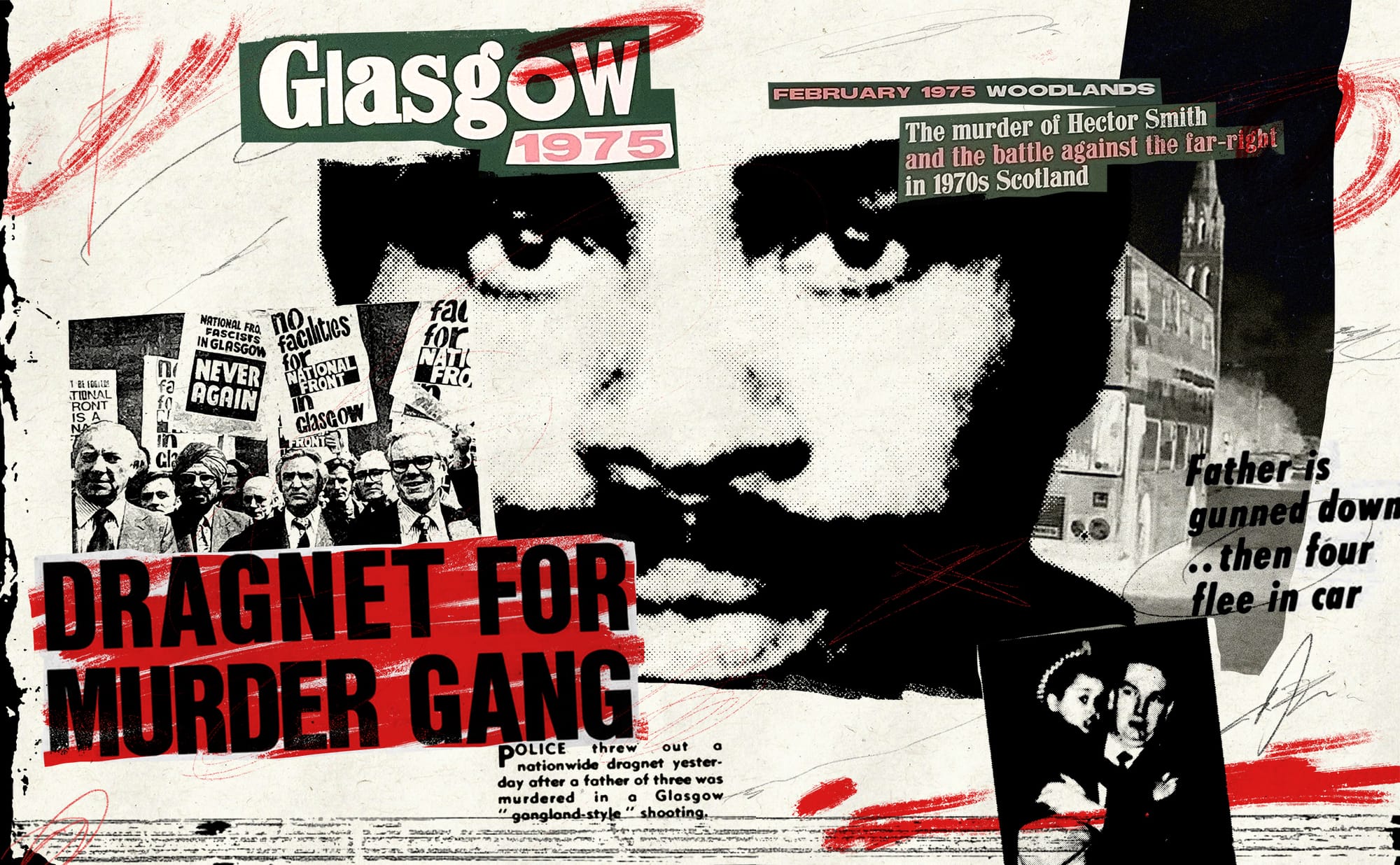

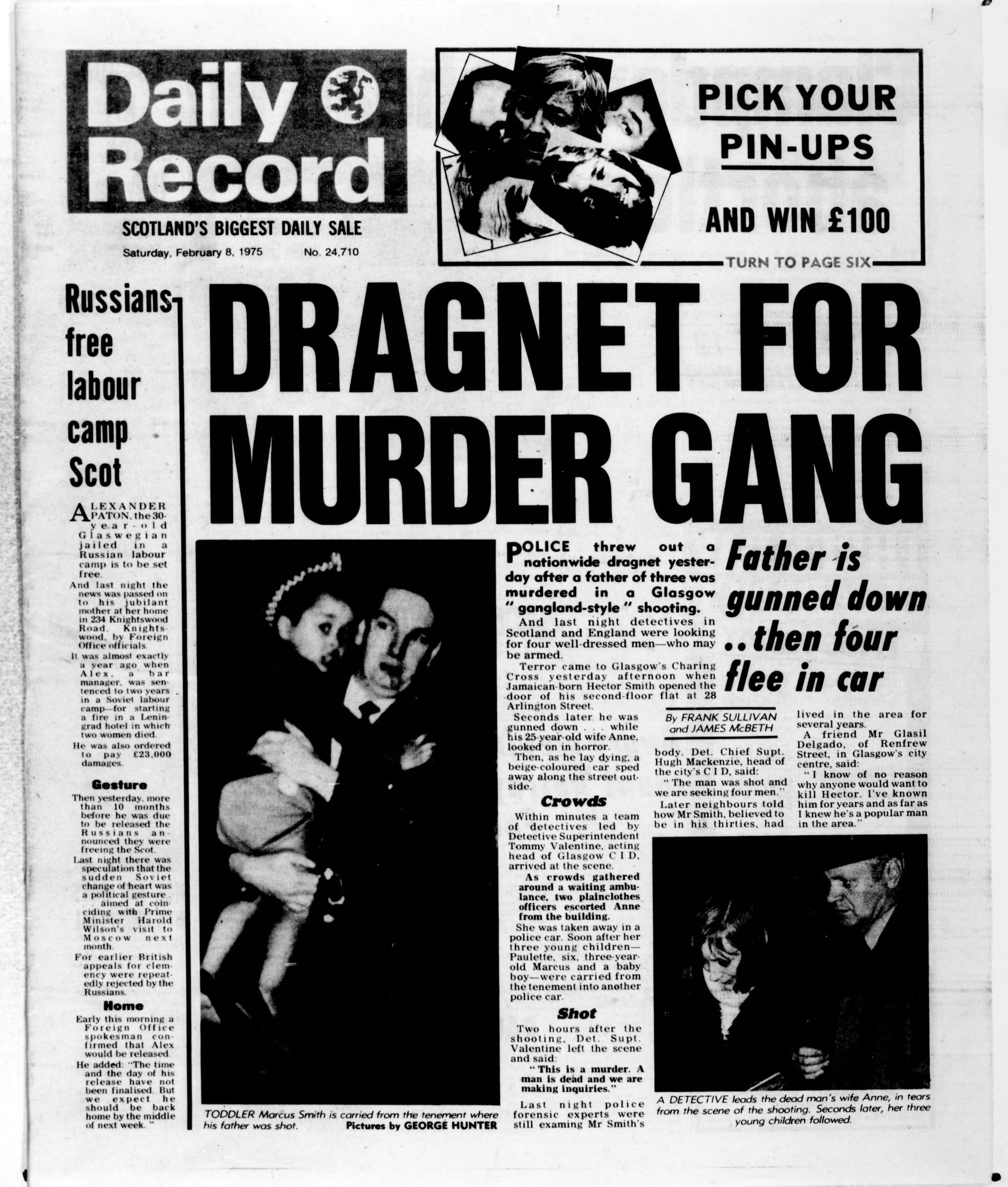

Hosie had returned to the house in Garthamlock clutching an early edition of Saturday’s Daily Record. Leading on the murder, the headline declared “DRAGNET FOR MURDER GANG”. It told of a nationwide search for four “well-dressed men” who had been seen fleeing the scene of the “gangland-style shooting” in a car. Photographs taken just a few hours earlier showed Ann and one of her children being led away from the flat by officers.

Nothing could have been funnier to the four men. They cracked up at the “well dressed” part and began rolling around the floor, imitating Hector’s death. But they would soon be brought sharply back to reality, as police stormed into the house shortly before 5am and placed them under arrest.

The High Court trial of the four suspects was expected to be drawn out, potentially taking weeks to get to the root of what was assumed to be a complex UDA fundraising operation in Scotland, amid tight security around the court and fears of paramilitary intimidation. Yet the strength of evidence from those who had seen what happened meant the prosecution case was wrapped up by the end of the first week, and the jury reached its verdict a few hours later. The four defendants were convicted of various charges, with three jailed. Only Hosie was convicted of murder. He had stayed silent throughout the trial, and his counsel had little to offer by way of defence.

The figure of Hector Smith, the victim of the brutal murder, did not loom large over the trial and it is striking how little was said of him. Only one newspaper ran his photo, and the single probing question about him was on the extent to which he spoke English. His wife confirmed it was his native language. In comparison, Hosie — the wayward “bearded six-footer”, the “Beast of Belfast”, the madman with paramilitary connections — was the subject of macabre fascination, in the court and in the press. The day after the trial concluded, huge photos of Hosie ran on most front pages, with the tabloids splashing with a shirtless photo of him where his tattoos were prominently visible.

Although the papers gratuitously splashed the N-word in banner headlines, repeating Hosie’s reported epithets, the racial dynamic in the case was underexplored, in what was branded each day by the press as the “UDA Murder Trial”. This theme only truly emerged in the summing up by one of the co-accused’s advocates, who for obvious reasons had an interest in painting Hosie as the lone, deranged extremist. Donald MacAulay QC told the court: “At first the National Front seemed to be a marginal issue, but it became clear that here was a rational and logical explanation for the death of Mr Smith... Is it a possible explanation for this dastardly murder that Hosie was so obsessed by his hatred of the coloured man, so crazed out of his mind by the sight of this man bravely resisting his attempt to extort money, that he shot him callously and brutally through the head?”

These comments do not appear to have provoked any wider discussion on racism in Scottish society. The papers remained more interested in Hosie being “bearded” than Hector being black, with an almost stubborn lack of interest in how he came to be in Glasgow, what his life was like, and what his family and friends had to say about him. It is important to note that he was not portrayed negatively — it’s just that not much was said at all.

Given the circumstances of the time, this is not hugely surprising. A small and dispersed population meant there was little in the way of Caribbean or African political or civic self-organisation in Scotland in this period — in contrast to the South Asian community. ‘The Troubles’ were also a sensitive subject in Scotland — over the sea and largely out of mind — and any political activity that invoked the conflict in Northern Ireland risked flaring up tensions, and usually did.

The UDA firmly rejected any association with the killing, and threatened Hosie with reprisals from their members in prison. The murderer spent most of the rest of his life in and out of the prison system. He became firmly embedded in white nationalist politics, writing unrepentant racist screeds to obscure fascist publications over several decades. He died in 2022.

The stories we tell are what make the city

Which criminal cases, victims and murderers are remembered — and why — is a complex question. Clearly this incident will not have been forgotten by those it impacted and traumatised. But for all the renewed interest in the histories of racism in Scotland and Britain, the podcast fixation on murders then and now, the abundant shelves of Tartan Noir in every Scottish library, and Glasgow’s ongoing and constant fascination with its past, Hector Smith’s name has not reverberated through the decades. Nor, for that matter, has Hosie’s. The case has not been written about to any extent for 50 years, and barely turns up an online search result.

A number of factors can help explain this apparent erasure from the story of 20th century Scotland. Five decades have passed, and even matters which caused a huge furore at the time are far from well known. Anti-racism as we now know it was in its infancy in 1975, with the mass organisations commonly associated with campaigning against the National Front, like Rock Against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League, yet to be established. In later decades, the murders of Axmed Abuukar Sheekh in Edinburgh in 1989, of Surjit Singh Chhokar in Lanarkshire in 1998, and Firsat Dag in Glasgow in 2001 all provoked a wide degree of debate and soul searching in Scottish society. In each case, there were campaigns for the murders to be seen as motivated by racism. But there was no precedent for this in the 1970s, and the case struggled to gain much societal or political reaction beyond the narrow constraints of court reporting and, briefly, as a tabloid human interest story.

Further still, it did not have the enduring lure of an unsolved murder or a miscarriage of justice. It was open and shut, solved within 12 hours by the police, and the trial had concluded less than three months later. There was not a dismissal of the idea that racism existed in Scotland, beyond the mind of one crazed individual, because that would imply the issue was even broached.

Just weeks after the trial concluded, the leadership of the National Front rolled into Glasgow in an attempt to hold a public meeting. A huge confrontation outside the city’s Kingston Halls saw 76 anti-fascists arrested and charged, including many of Scotland’s leading trade union figures. As we mark the 50th anniversary of that event this year, it is perhaps worth reflecting on the dangers of allowing far-right rhetoric to go unchecked. The stories we tell are what make the city, and it is for this reason that we should remember the events of 1975 in Glasgow.

Glasgow 1975: The Murder of Hector Smith and the Battle Against the Far-Right in 1970s Scotland is available from independent bookshops or online.

*Some names have been changed

A reminder: you can currently get your first three months of a Bell subscription for just £1 a week with our special summer offer. Sign up now to support local journalism at a 50% discount.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.