Robin Bans was barely 15 when they began to build the M8 motorway right in front of his family home. When he’d moved into the North Street flat with his parents in 1957, aged seven, there were identical rows of neatly lined tenements across the road, and more running all the way down to Anderston. Then, all of a sudden, they were wiped away by the wrecking ball, as if they’d never been there in the first place. Initially, Bans was taken in by the awesome power of the machines at work.

“It was quite exciting, seeing the hustle and bustle of it all — JCBs and trucks and lorries and huge, huge machinery,” he remembers. But six decades on from the destructive arrival of the M8, it’s no longer the cranes and bulldozers Bans recalls most vividly. Instead, it’s the people who were displaced — and the one friend he very nearly lost forever. All as a consequence of one of the biggest infrastructure projects Scotland had ever seen happening on his front doorstep: Glasgow’s inner ring road.

A few doors down on North Street lived the Lyons family. Bans soon grew close with one of the sons, Brian Lyons, who was the same age. “His older sister was a year and a half older, and was absolutely drop dead gorgeous. That was the reason I used to go up, but it never happened,” Bans says with a smile.

But the boys became fast friends. They would listen to records on the Dansette record player in the Lyons’ living room, bopping around to the likes of ‘Let’s Dance’ by Chris Montes. Either that, or they’d knock around the neighbourhood and play kickabout. They’d even escape the city occasionally, heading out of town with a few fishing rods and not returning home until dusk.

When motorway construction began, nighttime security was lacklustre. “We used to sneak in and explore the place, clandestine stuff, looking at the JCBs, actually getting onto the JCBs and trucks and the lorries, as kids will do,” Bans recounts. They also broke into the graveyard across from St Patrick’s church to play football together. “You used to find the odd bone,” he says with a chuckle.

Their friendship was important to Bans. For the first five years of his childhood, he’d been raised by his grandparents in Motherwell, years he remembers fondly. But when he moved back to Glasgow to live with his parents, things were different. He met his dad for the first time aged four and a half, but the bond never formed between them.

“It wasn’t a very happy upbringing. Culturally it was a shock,” Bans explains. There was more to grapple with than an emotionally distant dad. For a start, he didn’t know his name was Rabindra, not Robin, nor that his surname was taken from his father’s less foreign-sounding middle name, Bans. “I didn’t know my name was Singh, I didn’t know I was Indian, I didn’t know I was Sikh,” Bans says. He had to come to terms with the fact he wasn’t the boy he thought he was. “I cried for a whole year. It was really confusing, I couldn’t understand.” When Bans would visit the Lyons household, there was always something off with his dad. “I wasn’t aware of racism back then, but I knew he didn’t like me. I suspect it was racist,” he says.

Sorry to interrupt your Saturday read, folks. But where else would you read a twisting yarn about two long lost pals separated by the construction of the M8 over half a century ago? We firmly think local stories deserve depth, journalistic rigour and thoughtful writing. This is what we do at The Bell, if we don't say so ourselves.

To make sure you never miss another article from The Bell, why not sign up for free?

Concrete anaconda

When work on the motorway began, the side of North Street that the Bans and Lyons families lived on largely survived, but the other side was “totally and utterly demolished”. It wasn’t just the tenements that vanished overnight. “When [the area] got demolished, so did relationships, because the people that were there were dispersed to different areas within Glasgow.” Bans remembers the whole process of dispersal unfolding rapidly. “I don’t think folk had much notice to leave,” he remembers. “Looking back on it, it was almost like overnight. I lost a lot of pals, never saw them again,” he says wistfully. As for the planned inner ring road, it wasn’t to be. After public opposition to the construction of the northern and western flanks, the southern and eastern flanks were eventually abandoned, even if their ghosts haunt the city to this day.

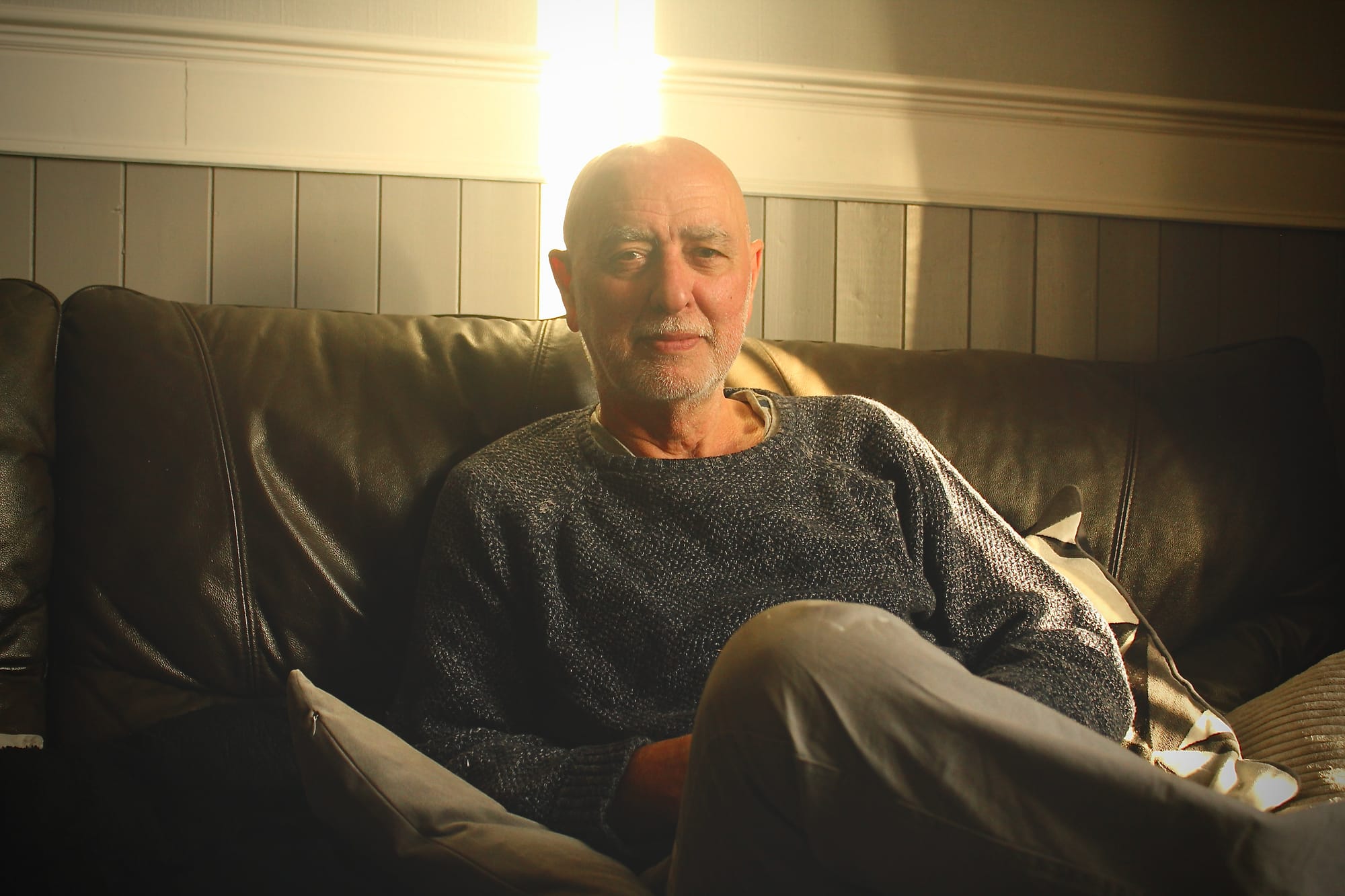

Bans is recounting this story inside his car on a rainy afternoon, on a break from his job as a driving instructor. His car is parked only a hundred metres from his old flat, and the deadening hum of Charing Cross is audible; an incessant stream of 150,000 vehicles zooming through the heart of the city every day. Wandering along to North Street, he points out his old close, next to the Bon Accord, and gestures upwards to his old living room.

Although the tenement block survived (until a fire led to its demolition years later), construction of the motorway displaced the Lyons family. They ended up rehoused in Hillhead, on Cecil Street. With the Lyons family gone, the childhood friends didn’t see each other for years. “When I look back on it now, it’s a bit sad, and back then I was upset. You never saw your best pal again because of the motorway,” Bans says. In 1968, the pair reentered each other’s orbits for a final night out at the Locarno Ballroom on Sauchiehall Street. But with the physical distance and time between them, tension had grown. They got very drunk. When Bans started getting off with a young woman his pal had been chatting up, Lyons lamped him. Bans still remembers the force of the punch. “I was pissed, but what a whack he gave me.” Later, they bumped into each other on the way home. “We ended up rolling around on the street like bin bags in the wind,” Bans says amusedly. The police arrived, handcuffed them, and locked them up. After Bans’ dad came and got them out of jail, they never spoke again. If the motorway was the first hit to their friendship, the punch was the knockout blow.

The wee flit

Bans got on with his life. He met his sweetheart, Rosaleen, and they were married in 1976. After the ceremony at St Pat’s, they wandered up the road to the Bon Accord for their reception, the rushing traffic of the M8 to their right. Years later, when Bans decided to become a driving instructor, his life was further fused with Glasgow’s urban motorway.

He and Rosaleen eventually moved a five minutes’ walk from where Bans grew up, first to Pembroke Street, then St Vincent Street in Finnieston, producing four kids. They all grew in the Finnieston flat, decorated with paintings by Bans’ own hand: street scenes reflected via puddles and his “version of abstract art” — a colourful countryside patchwork of fields.

Then, in January 2007, Rosaleen was diagnosed with myelofibrosis, a type of blood cancer. By March, she’d deteriorated, and was sent to Gartnavel for treatment. A few months later, Rosaleen’s sister, Cathleen, who’d been in remission with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, found out her cancer had returned. The two sisters even ended up on the same ward. They died, five weeks apart, in the spring of 2007, a “horrendous time,” Bans says. Rosaleen and Cathleen had been the family matriarchs. “It was more than just two people dying — everything died, because they were the heart of the family.”

Bans walks through to his kitchen, gesturing to a pristine Dublin stout mirror framed on the wall, a nod to Rosaleen’s Irish parents. They bought it together for their first flat right after they got married. “That was 1976, how long ago was that? 49 years. It’s amazing how the years go by.” He points to a sepia-tinged picture of Rosaleen in the hall, the first picture he put up on the wall. Years later, both walls are now completely covered with his hand-drawn illustrations and photos of the extended family, stretching outwards in all directions from his wife.

The first few years after Rosaleen died remain lost to Bans. He can’t remember much, other than desperately trying to stay afloat for the kids, the youngest of whom was only 15 when their mum died. During this period, Cathleen’s now orphaned son, Stephen, was sleeping on the floor at his older sister’s house, sharing a cramped flat with her husband and kid. Bans pulled himself together, cleaned up the spare room, and invited his 14-year-old nephew to stay. Last year, Stephen finally left St Vincent Street, aged 30. Bans trails off after recounting the story. There’s a pause, then a “Ha, it’s amazing, innit?”. The simple turn of phrase belies his glistening eyes and the emotion in his voice. Then, further underlining his selflessness, he’s immediately onto thinking not of himself, but others. “It was hard for Maureen because she lost her two sisters within weeks of each other, horrendous.”

‘Is your dad Robin Bans?’

Five years ago, a man found Bans’ daughter Rosie on her public Facebook page. He wanted to know if she was related to someone he knew over 50 years ago. The man, of course, was Brian Lyons. Rosie made the introductions, and the pair were reconnected after over half a century. Lyons left Glasgow in 1972, and had travelled the world since. He and Bans chatted for a while about the old times, then the conversation petered out.

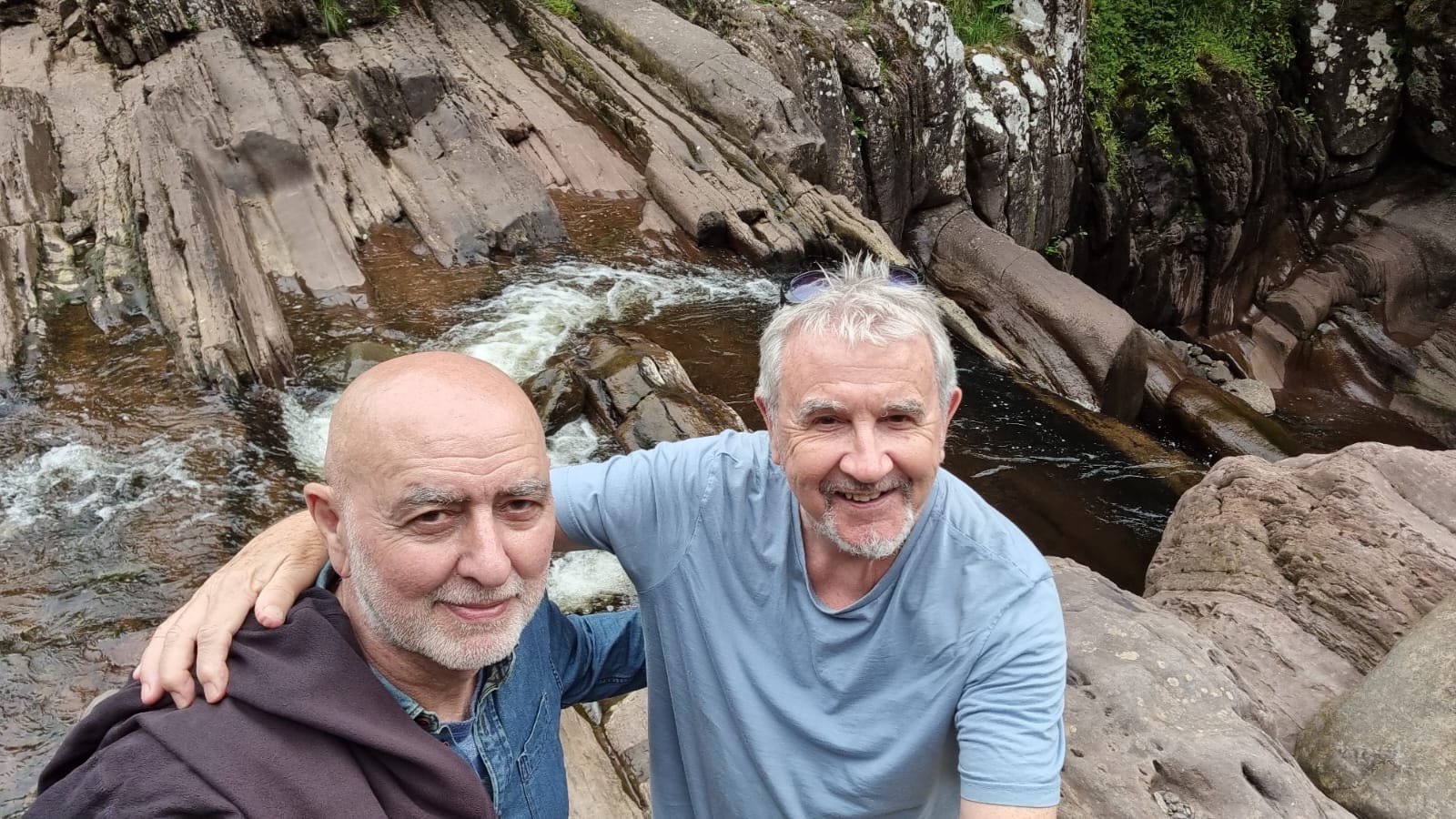

A year or so later, Lyons texted to say he was coming up from London to visit his brother — with whom he’d also become estranged — and asked if Bans wanted to go for a pint. “The minute I saw him and he saw me, I said ‘What’s happened to us, Brian?’ It was fantastic. I couldn’t believe it — I hadn’t seen him in 50 years,” Bans remembers of their first meeting.

For Lyons, the feeling was mutual. “We just chatted about the old times and memories and what had gone on,” he says excitedly. “And I said to him, ‘If you want to take a swipe at me in revenge for what I did, you’re welcome to’ — but he declined the offer,” Lyons explains with a laugh. “We just got on like a house on fire again.” He told Bans all about his colourful life.

“It’s unbelievable, what he’s done. He went to Mexico. He’d been to Cuba. He speaks fluent Spanish. He was involved in politics, he was associated with Tony Benn, the Labour politician,” Bans recounts incredulously. “He’s literally been all around the world, and I’ve stayed here. We’ve lived totally different lives.” Bans caught Lyons up on his kids, and the death of his wife. Lyons had no idea. They reminisced. Later, when Lyons’ sister died, he invited Bans to the funeral.

As Lyons had grown older, he’d finally decided to “let bygones be bygones” and reach out to Bans from the void, “as there’s only one life”. Although Bans had also got on with his life, he still thought of Lyons over the years, waiting in a queue at the chippy, driving along North Street, or back at the bar at the Bon. Lyons puts their separation down to “what they were doing by driving that hideous motorway through the centre of Glasgow” — but not entirely. When his family was rehoused in Cecil Street, he “began to hang out with a crew, which my dad called ‘ruffians’”. The next time he saw Bans, it ended in the violent outburst at the Locarno. Yet their friendship was still so lodged in his memory that fifty years later, he felt the need to reach out, see how his old friend was doing, and repair the relationship.

Earlier this year, Lyons was planning another trip to Glasgow. This time, Bans invited him to come and stay with him for four days. “He’s a bit of a recluse,” Lyons explains of his old friend. “He doesn’t go out much or do many things. He’d never been to the Trossachs, so we went to Callander. He’d never really been out walking,” Lyons says with disbelief. “These were first things for him, and he loved it. It was like a breath of fresh air for him, we had a great time.”

“We went to Troon,” Bans explains. It was the first time he’d swum in the sea. “I've paddled about, you know, but I’ve never swam in the sea. And I was like, ‘What the fuck am I doing? What have you done to me?’ I hadn’t been down that way for 25 years, since the kids were wee.” On their last night together in Glasgow, they went to an Italian restaurant, but the waitress was Spanish. “Brian broke out into fluent Spanish and she was astonished. They had a really deep conversation,” Bans says.

Nostalgia trip

Their rekindled connection shed new light on the old. “The thing is, I learned a bit more about Robin. I didn’t know about his childhood, how badly he was treated by his dad — separated from his real parents for about five years,” Lyons says. There is also a sense of regret at the way his best friend was treated in his own home. “In those days, dads were pretty shitty people,” he says. “I always remember going down to his house and feeling warmly welcomed, whereas Robin wasn’t that warmly welcomed in my house, mainly because they were mixed race.”

Although they lost touch, his friendship with Bans and another boy, Robin Ahmed, had a profound impact on Lyons. Aged 20, he joined the Indian Workers Association in solidarity with his old pals. “I was really affected by the way Robin [Ahmed] was treated due to the colour of his skin. It influenced me and my attitudes towards racism — the fact that they were my best mates.”

When Lyons was up in Glasgow, Bans told him about his Sikh heritage and the nearby gurdwara. It took some convincing, but Lyons eventually cajoled him into visiting. “I said, ‘I’m going to go in, even if you’re not’ — because he didn’t want to, because he’d rejected so much of his Sikh heritage that he had, because of his dad.” Eventually, Bans relented. “It was a fantastic, very warm welcome place,” Lyons says. They did a tour, had their dinner at the langar and sat down with some locals. “That was new for him,” Lyons says with a satisfied air.

For Bans, it’s been important to revive a friendship with “someone who knew me way, way back. We have some people that we know in common … It’s good to know they’re still alive, because at my age there’s a hell of a lot of people who aren’t here anymore,” Bans says. “[His] life was totally different yet he’s exactly the same, he’s no different. A wee bit older,” he says, but that’s it. “It’s funny how those feelings and memories are there but lie dormant, then I remember going up to his house listening to that record,” Bans says, remembering the Chris Montez 45’.

Their final evening in Glasgow at the Italian restaurant sticks out in Lyons’ mind. “He’d never been out on the town on a Saturday … We had a bit of a night out, we walked around. There was a lot of activity — people out in the streets having a good time,” Lyons says. “It was quite an eye opener for him, the whole experience.” Bans sent the family group chat pictures and videos of their night out together. “They were shocked,” Lyons explains. “They said they’d never seen anything like this before from their dad.”

Motorways away

Walking around Charing Cross today, there is very little evidence of the sort of neighbourhood where they both remember growing up. For Bans, the motorway “just changed the whole feel of the place. That community spirit really was ripped apart.” The area is now entirely defined by a Brutalist mass of concrete, four lanes wide in each direction — passing directly through the heart of what was once a thriving area, carving up one of Glasgow’s grandest Victorian crosses. Today, the Grand Central Hotel, and much more besides, is long gone. St Pat’s church — one of the few 19th century buildings that remains — faces imminent closure. The convenience of Glasgow’s busiest road has come at a cost to its people.

Meanwhile, the area continues to be reshaped, first in consultation rooms, then in 3D models, and finally by the wrecking ball and the crane. But few will mourn the recent losses in the way they did the buildings that came before. Portcullis House: a pile of rubble. Tay House, the Venlaw building and Elmbank Gardens: set to be demolished to make way for a hotel, flats and student accommodation — all part of the £250m Charing Cross Gateway development. Before long, a 36-storey tower called the Ard will become the tallest habitable building in Scotland, rising above the Charing Cross canyon, where rows of neatly-lined tenements once stood stolidly. The city never ceases to reinvent itself, even if its communities can seem tangential to the ceaseless march of whatever is currently deemed progress.

Once “many, many years ago”, before the old friends were reunited, Lyons had come back to Glasgow with his partner. He’d wanted to show her where he once lived: the Charing Cross mansions; the Baroque grandeur of the Mitchell Library; the old sandstone tenements. By then, his block had long since been torn down and was now “that grotesque Tescos place”. But the tenement block where his estranged friend had lived was still standing. They chanced their luck, and found the front door off the latch. “I couldn’t believe the door was open. So we went up there. I wanted to show her what it was like inside the tenement block.”

They climbed the stairs, only to find the name Bans was still on the door. His heart started to “beat like crazy”. ‘God, oh my god, oh my god. He’s still living here,’ he thought, the memories beginning to flood back. He knocked on the door and waited — but there was no response. Perhaps the flat had been vacated, but the family hadn’t removed the name, he thought disappointedly. Years later, when they reconnected, he had to ask Bans about it. Bans wasn’t sure if he was still living there at the time, but likes to think he was just out at the time.

Who knows, maybe he was out with one of his pupils, driving along on the motorway, the red ‘L’ affixed atop the Vaxhaull Astra, its wheels speeding across the Kingston Bridge. Perhaps right at the moment Lyons chapped on the door, the car had just ploughed its path off the slipway and down past their old North Street haunts. Either way, the place they once knew was no longer there, lost to a vision of the future that never arrived.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Bell and reach over 11,000 readers, you can get in touch or visit our advertising page below.