When a mains pipe tore open under Pollokshaws Road earlier this year, the tap water in a succession of Southside neighbourhoods cut out. A little reservoir sulking in the pipes at my flat trickled away. Then the tap heads twisted with a parched hiss. Does this sound like the beginning of something serious, I half-wondered. Water isn’t society until it’s taken away, and then it becomes unmasked as the baseline for everything you need to be civil. Coffee, showers, toilets. But also washing up, laundry, radiators. My neighbours offered some bottled mineral water, and I gratefully poured the dog his first (and last) bowl of Evian.

At last, by late evening, Scottish Water vans turned up and dumped crates of plastic bottles in the close — simply (and slightly ominously) labelled: “Drinking Water”. Meanwhile, gushing out from the broken pipe nearby was one of the most deluxe municipal water supplies anywhere in the UK — a feed from a great blue beauty of a loch so wantonly romantic that Sir Walter Scott felt moved to write an epic six-canto poem about it.

The next day, when the taps came back on, the water sputtered, but it was still glorious — the famously fresh “cooncil juice” brought to Glasgow from Loch Katrine up in the Trossachs. Water in Scotland is more than civility; it’s also a common wealth, an asset interchangeable with the famous landscape. Scottish Water is a public company owned by the Scottish government, and the cost of its work is bundled into the admittedly hefty Glasgow City Council tax (hence the “cooncil juice” nickname). In England and Wales water is a household bill paid directly into private coffers, with very mixed and unaccountable results.

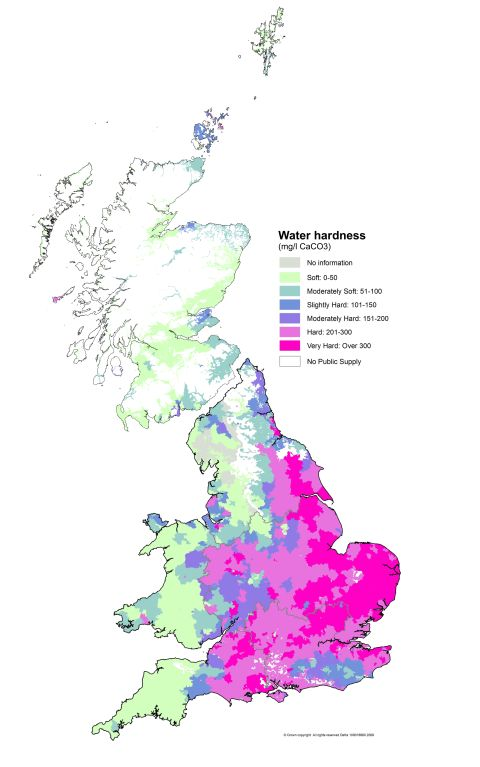

Most of the Scottish tap supply also comes from surface waters — rivers, lochs, burns — rather than ground waters, which explains its softness. It hasn’t had time to pick up the calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sodium in the rocks and earth that make for filmy cups of tea and chalky, stubborn lathers of shampoo.

Glasgow’s tap water is so soft and good it is even promoted to students at the University of Glasgow. The water is also used as a boast by Tennent’s lager, which talks about the Loch Katrine provenance of its biggest ingredient as if its brewers were trekking for miles to the source, rather than simply turning on a tap.

But all water companies — and all tap drinkers — now face an equal threat: the warming of the planet. Up at Loch Katrine, work has already begun “to secure the next century of water quality” says ecologist Dr Mark Williams, head of sustainability at Scottish Water. Climate change is going to change the cost and quality of what comes out the tap, he says, unless we adapt the landscape itself to prevent erosion from heavier rainfall and longer dry spells.

He shows me a picture of a huge exposed gash, or “hag”, in the peat above the northern edge of the loch, taken this year. “There’s a huge amount of peatland in the upland areas that needs improvement,” he says. “The organic material is being washed out into Katrine. When it rains, you want the water to hold in the peat.” The poorer quality of the peatland has developed over time by draining water for the benefit of sheep grazing, along with the natural vandalism of deer trampling down vegetation. When combined with the wilder rainfalls that come with climate change, this erosion leads to run-off from the peat, rather than retention of water in the bog. Decay of plant matter in the peat hags also gives off carbon.

The more all of this happens, the more the water needs expensive treatment to make it fit for consumption, a cost that will ultimately fall on the consumer. Scottish Water’s plan is to create a carbon sink and better drainage in the land around the loch. “It’s a long term project, and it will see a new native woodland with a mix of upland deciduous broadleaf and Scots pine, birch, and rowan; we’re also managing grazing and restoring peatland,” Williams says. He adds that Scottish Water regards the Katrine estate as a “real signature area of land, it is an example of us trying to do the right thing.” The 10-year plan was approved last year, and the first phase began in January.

Lovely though Glasgow’s water is, it has still been sanitised on the 34-mile journey from source to city. So I decide to drive up to the loch for a drink of winter water in its purest form. A soft, gloomy squall has arrived before me. Close to the shoreline, the water chops from black to brown, the colour of wet tree roots. Further up the loch, against mysterious skerries and wooded islets, sheets of water are pulling in grey gusts in the crosswinds.

Two small boats, the Rob Roy III and the Lady of the Lake, are tied up alongside the grand Walter Scott steamship, and all three idle their engines at the southern pier, waiting for passengers. The “earlier world” of the 450-million-year-old Arrochar Alps that Scott described surrounding Loch Katrine in 'The Lady of the Lake' looms high over the scene, poised to reassert total mountain power after the pleasure boat timetable stops at 3pm.

There are two main types of water here: the wild and the tamed. Just along the tarmac road that snakes for a few miles around the north-east lochside, there are padlocked gates to Scottish Water monitoring stations, and a long stone terrace brings a loud, organised chute of gushing water down from Glen Finglas waterfall, with the banks of the loch itself held neatly by a stone wall.

The managed side of the water has been in action since the mid 19th century, when fast-growing Glasgow was festering with slums, cholera and typhoid. It really needed a clean drink of water. Victorian engineers stood in this same spot and, in spite of the need to cross several wide and deep valleys, and with no comparable waterworks project anywhere in Great Britain, decided that they could still pull off the construction of an aqueduct all the way from loch to city. They were right.

For their 'Katrine aqueduct', which still carries Glasgow’s water supply, they had to bore tunnels and lay three-foot wide cast-iron pipes through whinstone, gneiss and mica slate riddled with quartz veins. Its raised sections were hoisted over rushing rivers and ravines, requiring 3,000 workers to finish it over three years. The work was paid for by the city at a cost of around £1.5m (equivalent to about £176m in today’s money), with the start-up costs loaned to the waterworks company using Glasgow’s own property assets for security.

Appropriately, it was raining royally on October 14, 1859, the day that Queen Victoria sailed up Loch Katrine to cut the ribbon on this grand new showstopper of municipal engineering. The heavens opened. “Incessant torrents”, in the words of the Scotsman’s reporter at the time. “Down it came in perfect sheets of wet.”

Enjoying Natalie's Loch Katrine love letter? You can get two totally free editions of The Bell every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below. No cost. Just old school local journalism.

As the squall settled into a downpour, I could picture the monarch’s short, stout profile heading for the shore in all her dreich pomp. But I found it surprisingly hard to get close to the water itself: the raised stone wall following the road is in the way. In the end I took a sip from a little waterfall trickle coming from the bracken-and tree-covered sides of Primrose Hill, to the right of the road. It was clean and sweet, but I couldn’t taste it without thinking of the threats Williams mentioned from the past — sheep parasites, for one — nor for those he talked about for the future: algae and other hotter-world poisons.

More than water

If you want to be assured that Glasgow’s present council juice greatness isn’t just myth or marketing, ask a speciality coffee barista. Matt Cowie, the co-founder of Amulet Coffee, which opened in Partick in the West End a few months ago, is obsessed with the city’s tap water, which he describes as sitting at the “high end of the spectrum” but intriguingly also “a perfect baseline to build an even better water off of”.

Bottled mineral water is not necessarily as nice as Glasgow tap, he insists. But for his coffee to taste as good as possible, it still needs some tweaks — albeit to a lesser, and less costly degree than the London speciality shop brigade, who have to resort to reverse osmosis to manage the capital’s hard-as-nails water.

“The future of coffee is all in the water,” he says. “It’s the biggest upgrade you can give yourself after a good grinder. Glasgow is so soft compared to London, it’s infinitely better. It’s already basically distilled.” Even so, he says, “every morning we batch up 10 litres of our own water, we add magnesium, calcium and potassium”, hardening the tap water a little to a secret sauce level. “Minerals affect the way we perceive the aroma, if the water is too soft you’re leaving flavour on the table.”

This aspect of specialty coffee is new to me, but water seems to be taken very seriously by most self-respecting practitioners. “All the cutting edge places have excellent water science,” Cowie says. “Greytone in Bristol has amazing water, Zennor filter coffee [in Glasgow] is so good.”

Another nearby Partick newcomer, Kahawa Mzuri, is run by Kieran Darlington, who grew up in Nairobi, Kenya, where many homes don’t have tap water, he says, but instead use water filters and gallon-water butts. He came to study in Glasgow – and decided to stay. He is now using his cafe as a showcase for Kenyan speciality coffee, and working with producers who promote ethical farming and trading. Like Cowie, he has a nuanced appreciation for refining the local tap water. “Having some mineral content also helps you perceive different flavours.”

He notes that “Almost all speciality shops will have a water filter attached to their espresso machine. The tap water won’t be the same as what’s in the shop. But what we have in Glasgow is a really good starting point, we can play around with the mineral content without too much difficulty. We’re in a good position here.”

The future of thirst

Throughout the course of my research, I keep coming back to something Mark Williams suggested to me early on: that your view of “good” water depends heavily on where you grew up. Williams, for example, said he’ll forever hold the tap water from Llandegfyd reservoir in south Wales in his heart. I also grew up in south Wales, but took the clarity of its water totally for granted until I spent more than a decade living in London, feeling unrefreshed by the municipal mouthwash effect of every glass from the tap. After years in Glasgow I’ve come to really appreciate the big lungfuls of tap that you can drink without feeling like a chlorinated fish. And in winter, I love the chilliness of it too, thanks to the temperature of the pipes, of course, but also as a reminder that your thirst is being met by an arm of the sea.

The mountain auras of Loch Katrine have run down Glaswegian throats ever since Queen Victoria’s dousing on a dour day in 1859, apparently wearing a Stuart tartan dress, white bonnet and a black veil. Onlookers sniffed that she was dressed “plainly”, but it was an appropriate choice to mark an everyday luxury afforded to anyone who calls the city home.

But the open banks of peat in the Trossachs spell a warning of a possible future — a universal “Drinking Water” treated so vigorously it tastes of nothing but the treatment plant. When work resumes at Loch Katrine on the creation of a new forest, it will be a quieter affair than the bombastic Victorian rock-blasting: instead, it will rely on planting, repairing, and clearing. But it’s no less significant for maintaining Glasgow’s water. As another of Scott’s lines has it: “Within Loch Katrine's gorge we'll fight”.

Welcome to 2026, year of The Bell. We’re Glasgow's new newspaper, delivered entirely by email. We hope you enjoyed Natalie's lovely piece about the source of our tap water. So you don't miss future stories like this, sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Bell every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece like this one.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.