Table of Contents

“Donald Trump is a very disruptive man, but did he not get peace in the Middle East?” I don’t quite know how to answer this, but it doesn’t matter; Colin McInnes is steaming on regardless. The 33-year-old founder and director of Homeless Project Scotland is making a case, and a comparison — to himself. McInnes is not short of accusations of being disruptive. But he’s not out to “cause trouble” for the sake of it, he protests. He just wants to “save lives”. Not everyone agrees.

The lives in question are those of some of Glasgow’s most vulnerable: the figures that can be seen huddled in doorways and on park benches every night. These are the dozens of rough sleepers and thousands of homeless people who populate the city. Two years ago, accusing the council of failing in their duty to address the plight of the unhoused, McInnes launched Homeless Project Scotland’s first night shelter in the city centre. It was the opening salvo in a conflict that has run and run.

Since then, as McInnes tells it, he’s been in a struggle with the state to keep the place open. The council are trying to evict him, (apparently) evidenced by the most recent showdown with the planning committee where they refused HPS’s application to run the night shelter on a technicality. (Councillors encouraged McInnes to submit a new one by the end of January.) McInnes says this was an attempt to kick him out — the council say they are just following procedure. This wrangle has taken centre stage in the public eye.

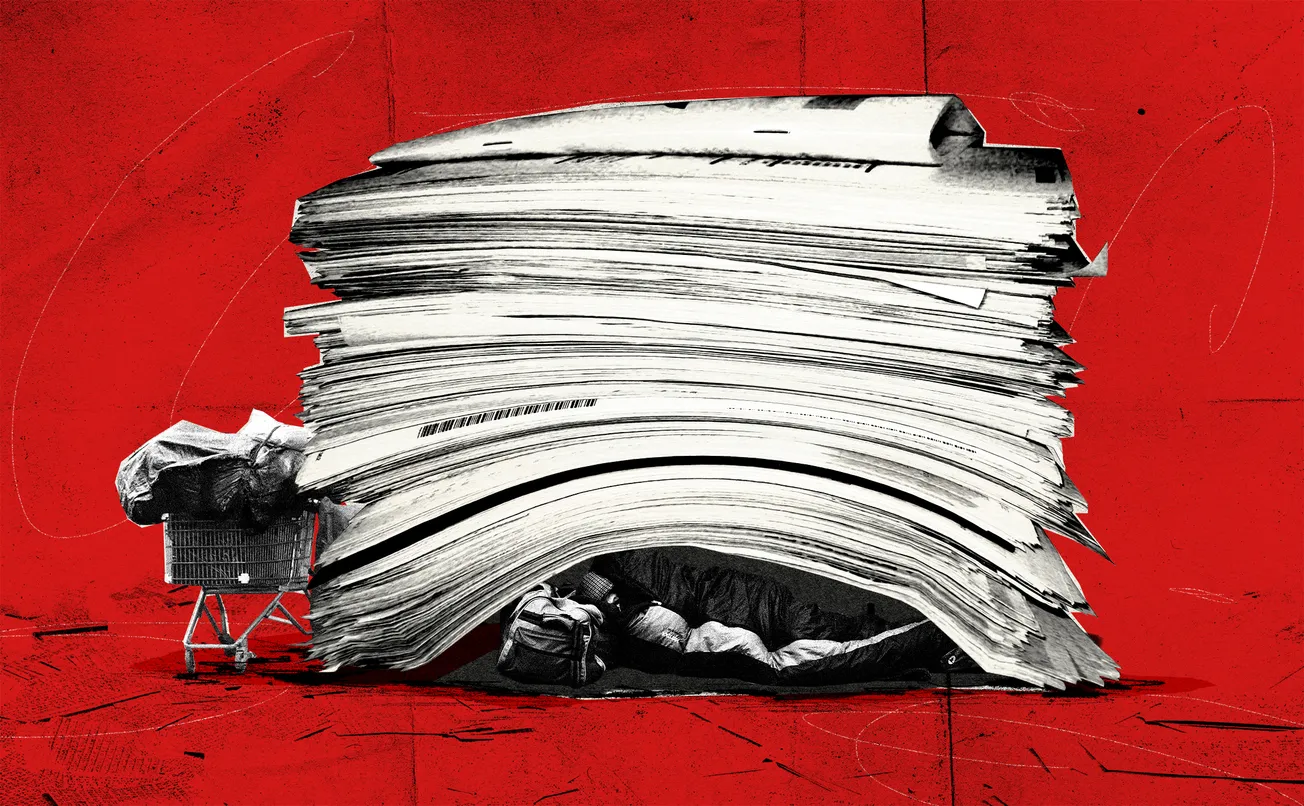

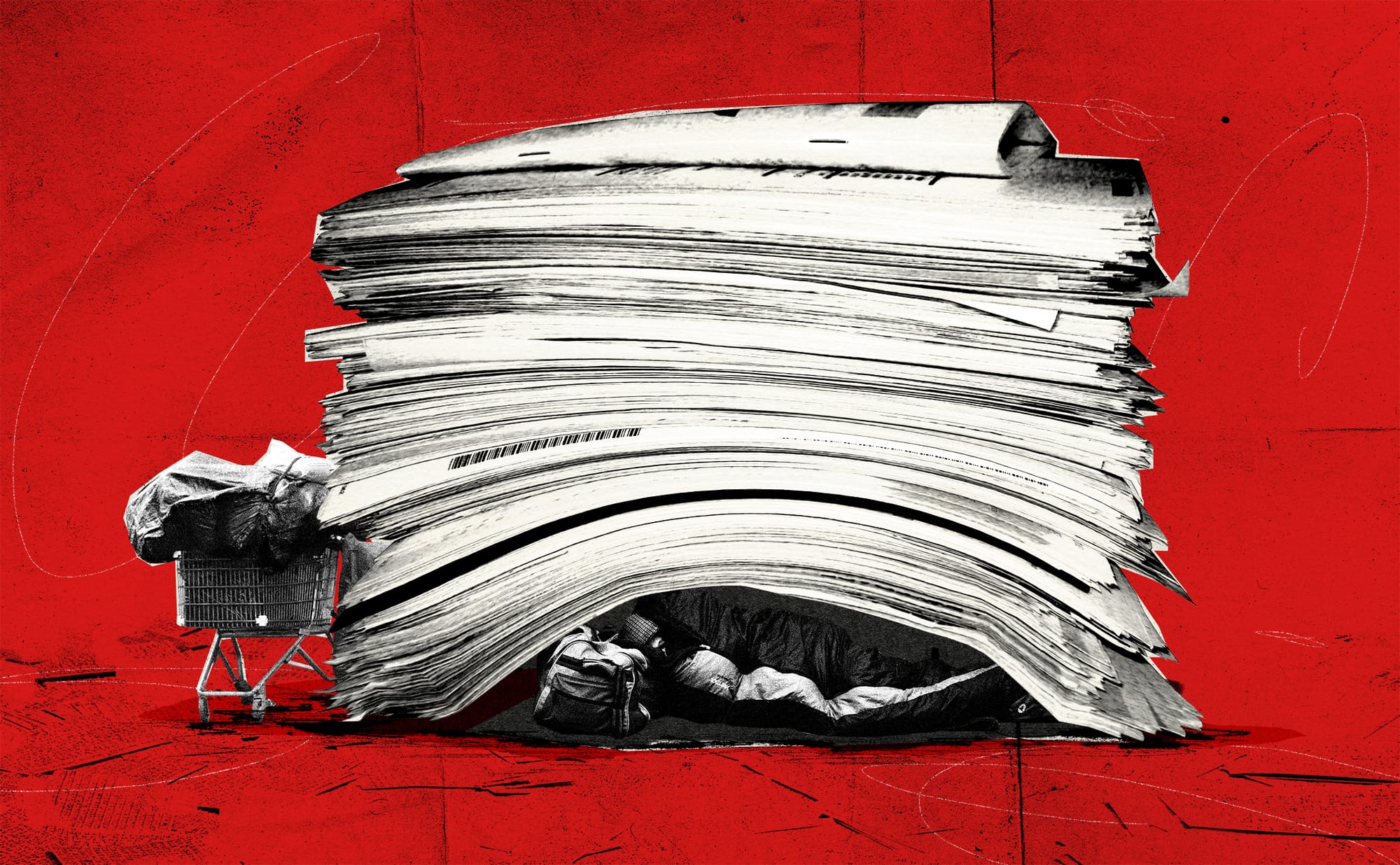

But, behind closed doors, a different siege is being waged in the courts by Homeless Project Scotland, one which poses an existential question about how homelessness is handled in Glasgow — and just how big the scale of the issue is. Homeless Project Scotland claim they have found a way to uphold the legal rights to accommodation of almost every homeless person in the city. The council and other frontline charity workers contest this. Via their new legal strategy, McInnes’ organisation, they say, is draining resources and actually preventing people being housed.

So who’s telling the truth?

A new legal strategy

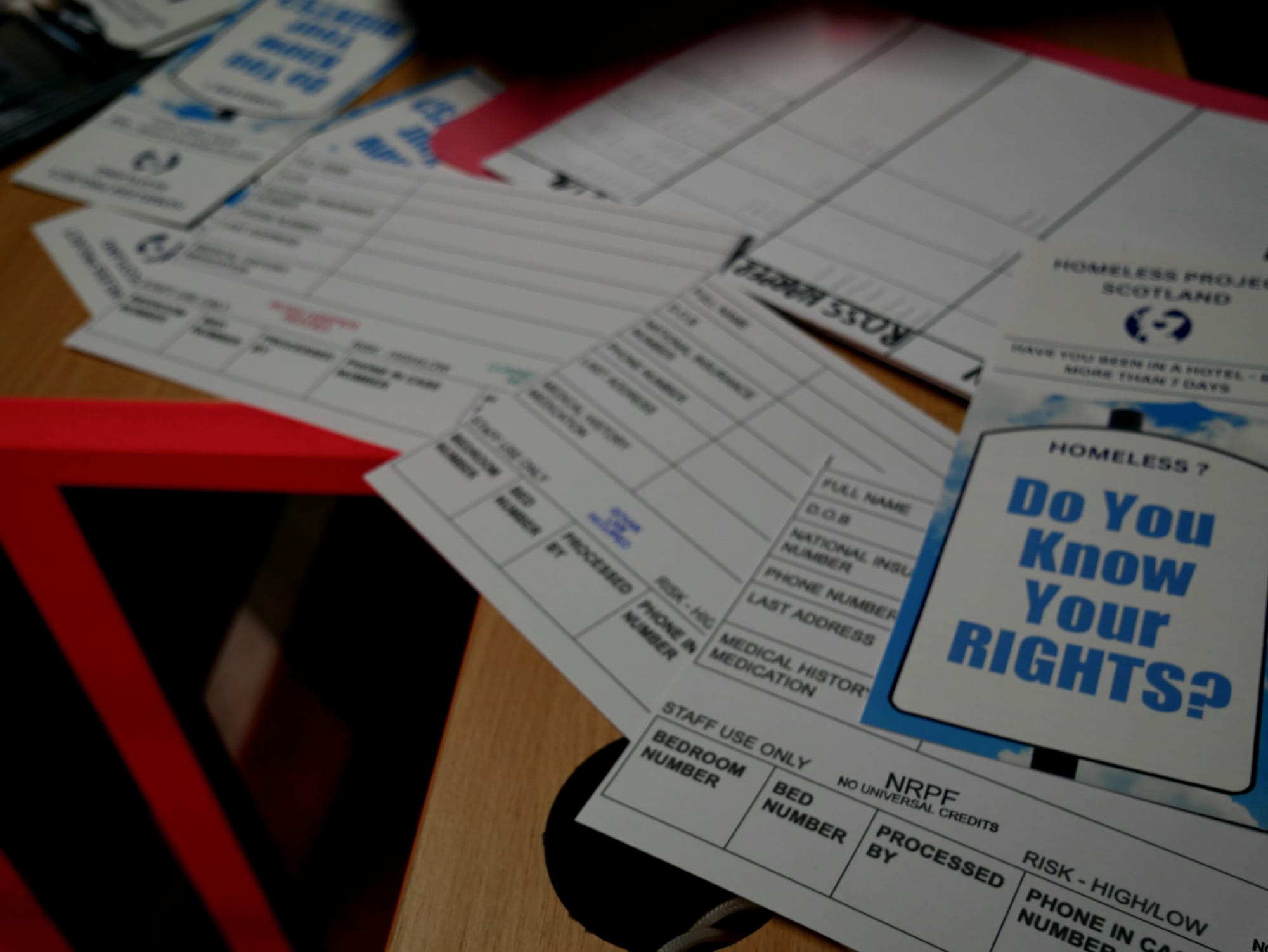

The huddle outside 67 Glassford Street would give a hint as to its function, even if I wasn’t already acquainted with the building. By 10.30pm on a freezing November night, the crowd waiting for the Homeless Project Scotland night shelter is already 30 deep, and shivering. One by one they’re ushered inside to be registered for the evening. I take a seat next to Sebastian, a volunteer manning the front desk. Despite confiding in me that he was recently resident in this night shelter himself — his current situation is still “tricky” — the twenty-something is flashing every chilly client who comes his way a relaxed smile, entering their details in a colour-coded spreadsheet. When Sebastian’s finished, he hands the person on the other side of the desk a stamped paper slip. It either bears the name of an assigned legal firm or the acronym, ‘NRPF’, meaning no recourse to public funds — aka, asylum seekers or people without permission to be in the country and not eligible for council support. Proceeding to the basement with their strip, the client heads over to a table where volunteers help them fill in forms and understand what they need to secure housing.

It’s an impressive set up and I tell McInnes so. He’s next to me, imposing 6ft 2 frame looming over the computer, to give a real-time demonstration of Homeless Project Scotland’s new legal machine. McInnes, with his trademark persuasive certainty, claims it’s saved “thousands” of lives.

I see it in action a moment later when Andrea, a longtime service user, arrives. She shows McInnes a sore on her tongue while Sebastian clicks around on his spreadsheet. A second later, he flags that Andrea already has a case open with the council. She’s got an established legal right to emergency accommodation. It’s time to call the council.

Hi folks, we're briefly interrupting your Saturday read so we can ask, where else would you get this sort of rigorous approach to a complex but vitally important story? And we don't just tell you, we take you in the room, in the night shelter, in this case. We believe Glasgow's stories deserve to be told properly. This is what we do at The Bell.

To make sure you never miss another article from The Bell, why not sign up for free, no card details required?

See, if you’re homeless and have a strong enough connection to Glasgow, the council has a duty to find you housing once you’ve registered as homeless. If it doesn’t fulfil that duty, it exposes itself to legal action. A housing lawyer can force their client’s case by threatening the council with a judicial review — costly and drawn out cases in the Court of Session. Usually the council will end up accommodating the client, in hostels or temporary hotel rooms if nothing more permanent is available, which it usually isn’t.

Andrea’s open case means the council knows she’s got an entitlement to be housed. So Sebastian rings the council. There’s a painful five minutes on hold but eventually someone from the out of hours emergency accommodation team picks up. Sebastian speaks to him, McInnes speaks to him. There’s confusion. The officer says he can only speak with Andrea herself. McInnes insists the council has received a mandate from Andrea allowing HPS to act on her behalf. Exasperation palpable, the officer replies: “that’s the law”.

“Barriers”, McInnes intones darkly. Andrea comes back upstairs and speaks to the man on the other end. He offers her somewhere in Govan for the night. Result. Only, Andrea looks anxious, “I cannae go Govan, it’s not good for me”. The officer says that’s all he has available. And so Andrea is to spend another night at the HPS shelter.

This was the McInnes machine working as intended. Andrea arrives, they get the latest update on her situation, call the council, and she gets offered a place. It’s Andrea’s decision not to take up the offer, but Homeless Project Scotland will still support her tonight and in future efforts to find accommodation.

This legal operation is courtesy of Homeless Project Scotland’s new associates: Ross Harper Solicitors, a law firm based in Kelvingrove Street and with a drop in at the Glassford Street shelter. It’s helmed by Nigel Scullion, a lawyer specialising in criminal defence. He has resurrected the name of one of Scotland’s best-known law firms, Ross Harper and Co, shut down in 2012 and had directors struck off over inappropriate use of legal aid fees. In March of this year, Scullion — who has been involved with Homeless Project Scotland for “years”, volunteering in the soup kitchen at first — came to McInnes with a proposal: he saw the mountain of homeless cases piling up and thought he could strong arm these people into accommodation. “I just want to get people off the street”, Scullion says when I meet him the following morning in a Finnieston cafe. He’s slick in a slim-fitting white shirt and tie, voice booming. This is not someone who shies away from attention.

Through “collaboration,” says Scullion, he and McInnes developed the administrative conveyor belt I witnessed Andrea being processed along the night before. What I didn’t see is Scullion’s role if a client fails to be accommodated by the council, which begins the following day. He, or one of his team, will open up their emails and get to work, sending a legal challenge to the local authority, warning that if they don’t accommodate the affected person, Ross Harper Solicitors will apply for a judicial review. They’re prolific: between May and September 2025, Scullion’s firm has threatened the council with applications for judicial reviews on 2058 occasions. In fact, Ross Harper was responsible for 87% of judicial review threats concerning Glasgow city council’s housing duty submitted in that period.

Wasting time or saving lives?

Yet the council say that Homeless Project Scotland’s new tactic has an unintended effect: it’s actually stopping people being housed by clogging up bureaucratic machinery with all the legal complaints. Alex*, a frontline worker for a Glasgow-based homeless organisation, agrees that finite time and human resources at the local authority are being hogged by HPS.

Alex doesn’t want their charity or themselves to be named — they say McInnes already “despises” their charity, and doesn’t want to make things worse. But their clients are losing out, they claim, as HPS’ aggressive tactics mean housing officers are preoccupied with their service users.

Glasgow city council also objects to the onslaught, saying the extent of the legal claims are "unnecessary". They share figures with The Bell, which they claim show Ross Harper Solicitors is sending hundreds of what they call “duplicate” letters — i.e. legal threats over a case which has already been raised. In July alone, the council tells us, the firm lodged 504 duplicate claims. A council spokesperson said they “could not object” to reminders being sent about a case, but “these are not reminders... “Time is wasted checking the case and working out that the matter is already in hand”.

As for the manpower, Glasgow city council estimates that it takes four legal personnel — three solicitors and a trainee — to deal with HPS’s legal threats during a five-day week, working out roughly “to a solicitor a day”. The cost of this is that “plenty” of other work the staff could be doing has to wait until after the legal threats are dealt with.

The council has an interest in proving that many of Ross Harper’s case communications are duplicates — after all, if every one of the 2058 communiques sent between May and September represent a unique individual, it means that Homeless Project Scotland and Ross Harper are responsible for getting roughly half of all 4127 people registered as currently being temporary accommodation in Glasgow seen to by the council. This would make them the single most effective organisation in the city when it comes to enforcing their clients’ right to housing. It’s not a title the council might want bestowed on their longtime bête noire.

Scullion disputes the claims of ‘duplicates’. The council’s claims, he says dismissively, have “no merit whatsoever”. The caseloads reflect the scale of the housing emergency, nothing else to it. “There’s no tricks”. And even if the same case is sent over twice, it’s necessary — it just reflects a change in the client’s circumstances.

“Why would there be duplicates?” he asks rhetorically. “We don’t get paid for them”.

Ah, pay. Is that a motivation?

Scullion chuckles. “I like your endeavour”, he says. It’s not an answer.

So I ask again. How does he pay the Ross Harper paralegal based at the HPS night shelter?

Scullion is resolute. “I’ll not be discussing that” he replies firmly. “There’s no financial incentive for anyone to do this”.

Isn’t there, I press?

Scullion admits he “doesn’t know yet” if the enormous case load Ross Harper has taken on in the last eight months makes “financial sense”. He’s pre-empting cynicism about his motivations, continuing: “We have to fight and justify every penny” of legal aid funding, he explains. Ross Harper, he adds, is subject to audit by the Scottish Legal Aid Board (SLAB) and the Law Society. The latter is underway, and such scrutiny, Scullion describes, is “intense”.

Given public money is on the line, I try to drill into the cash side more. The previous night, McInnes had told me that there is a maximum of £135 in legal aid fees a solicitor can claim for a homelessness case. Scullion confirms this when I ask, but says “fees average between £50 and £100” and rely completely on how long a case takes, which has to be painstakingly detailed to SLAB. Nonetheless, 2000-odd cases would equal a payout of roughly between £100,000 and £200,000.

As for claims that Homeless Project Scotland’s endeavours are seeing others lose out, Scullion is scornful. “My duty starts and ends with my clients”, he says, defiant.

If you've made it this far down the article, surely you'll enjoy more of our writing? To make sure you never miss another article from The Bell, why not sign up for free?

Means to an end

Meanwhile, digging into HPS so far doesn’t seem to suggest wrongdoing, so much as an organisation that shares a deep, mutual mistrust with official channels. There’s no doubt council resources are being stretched by the barrage of paperwork and legal threats, but HPS are enacting the legal rights of their unhoused clients. The difficulty perhaps lies in enmity that has grown between the local authority and the grassroots organisation, thanks to their very different ways of tackling the same problem (both HPS and the council are keen to stress that their icy relations are thawing somewhat, although I didn’t see much to support this).

“I know they’re understaffed”, Scullion says of the council, “but there’s got to be a better way of working”. As for the criticism from others? He’s not bothered, “f***” everyone else”.

He and McInnes are not budging on their method either. Though both are aware it’s putting extra pressure on the local authority, to them, the ends more than justify the means. McInnes sees it like this: “I’m not here to do what’s best for the council. I’m here to do what’s best for the homeless person.”

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.