The final day was as farcical as the lead-up. There was no announcement. Instead, a smattering of visitors turned up to find the gates locked and a handwritten sign. Soon they were outnumbered by press, milling like scavengers circling a dying animal. Eventually a member of staff came to the gates. The zoo would not be opening today, they explained. Indeed, it would not be opening again. It was a strange, anti-climactic end to a saga that had inflamed public opinion and dominated local news for months.

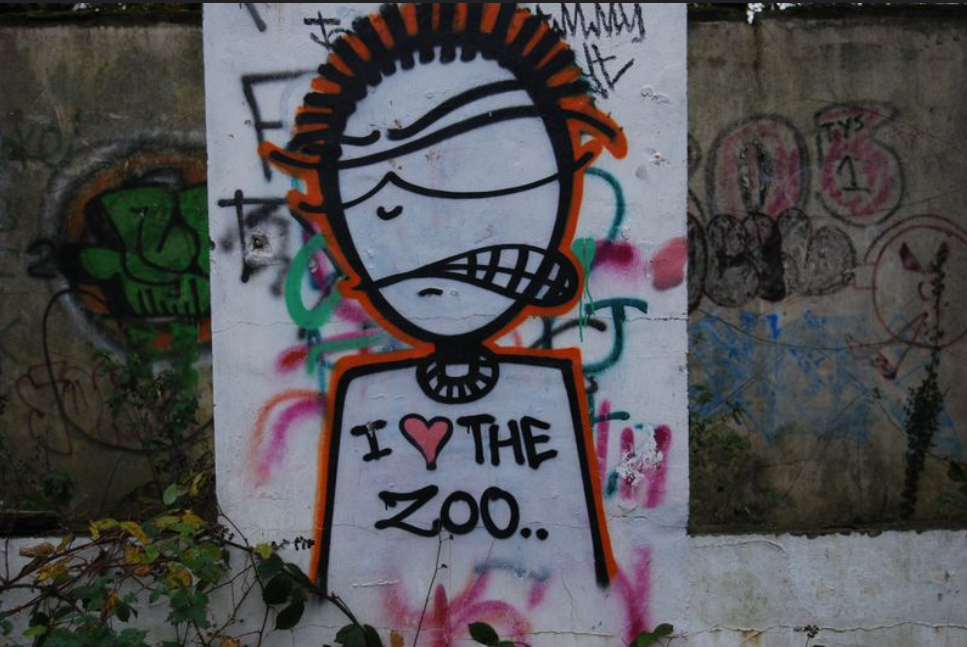

More than 20 years on, few traces of Glasgow Zoo remain. However, in its half century of existence, the zoo held a specific space in the imagination of Glaswegians. Some conflate it with the happiest of childhood memories, while others were haunted by what they saw there. Even today, the zoo remains a source of contention.

Early years

Glasgow Zoo — sometimes called Calderpark Zoo — opened in 1947. After a hunt for a suitable site, eventually the Zoological Society of Glasgow and West of Scotland selected the Calderpark estate to the east of the city. The first 25 years were fraught. Funding was a constant challenge, and the Society relied heavily on donations and corporation subsidies.

1972 saw the arrival of a new director, Richard O’Grady, who would come to be synonymous with the zoo. Born in Cambridge and at the time just 26-years-old, O’Grady was a graduate of Dundee University, with a degree in biology. He had previously worked at Culzean Castle, which he had helped develop into Scotland’s first educational country park. O’Grady was clearly a man of not inconsiderable energy, his personality described as ebullient in more than one profile.

This enthusiasm would soon be tested. Upon arrival at the zoo, he was confronted with a site that was both underfunded and severely dilapidated. O’Grady himself was scathing around the conditions, describing to The Herald “old, diseased animals crammed into cages barely fit for a travelling circus.” He found himself thrust into multiple roles: estate manager, maintenance worker, zoologist, and fund-raiser, and quickly established himself as a passionate defender of the zoo.

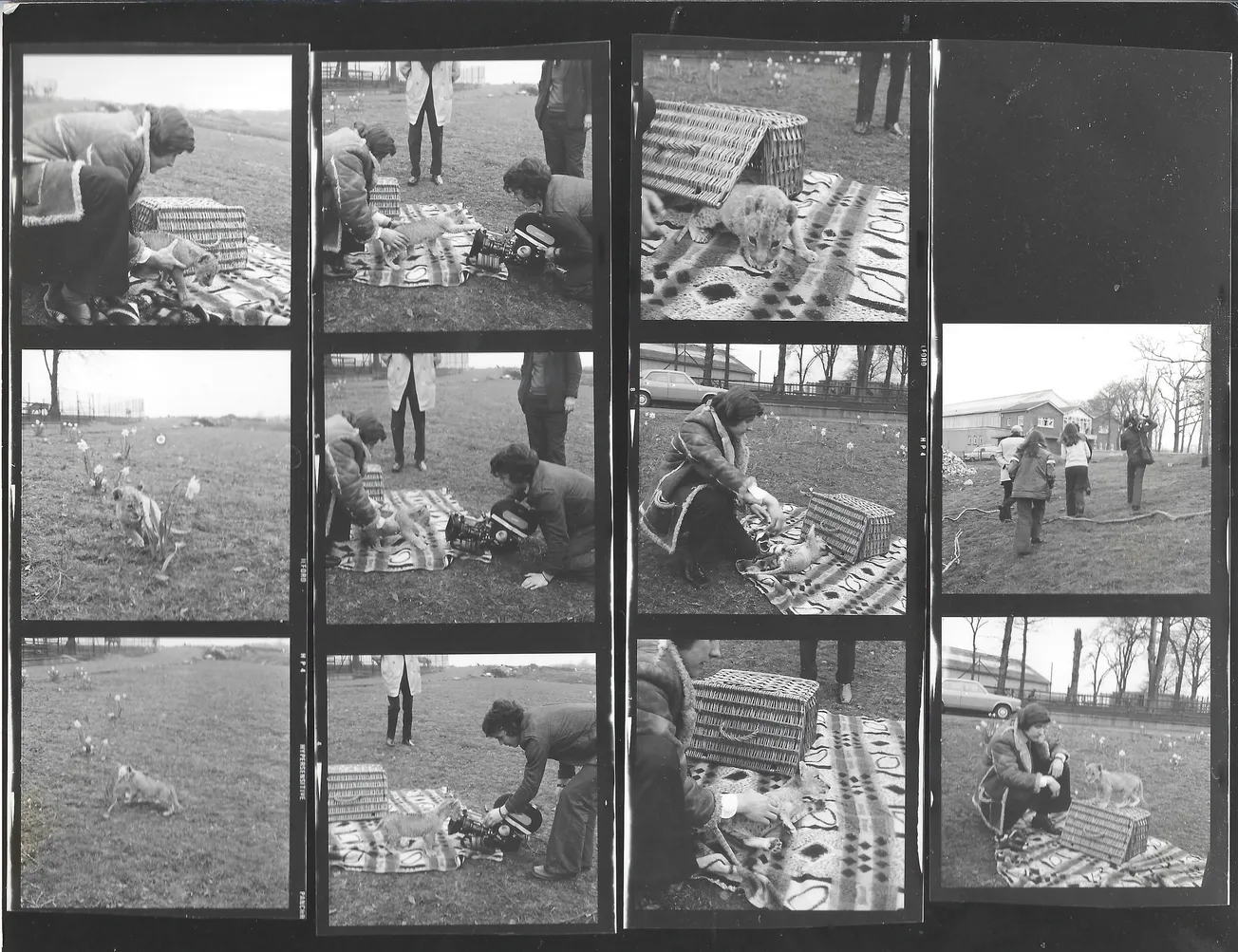

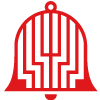

While the institution struggled for funds continuously, from a zoological perspective, there were notable successes. The big cat breeding programmes were world renowned, and the Black Bear enclosure was considered innovative and exceptionally well-executed, winning praise form both zoologists and animal welfare groups.

O’Grady became something of a public figure, which he embraced. He appeared as a regular guest on children’s television and wrote a weekly column in the Daily Record. He seemed to operate under the maxim that there was no such thing as bad press.

Paul Paterson was a senior keeper at the zoo in the latter years of O’Grady’s tenure. Now a freelance photographer, Paterson is impassioned when he talks about the zoo and displays remarkable recall of events upwards of 25 years ago. He describes O’Grady as “a maverick, with a mind that jumped from subject to subject and off on unrelated tangents. He was hyperactive both in his thoughts and mannerisms.”

Despite this, the toll of his work would start to manifest itself, both in him personally and in his beloved zoo.

The decline begins

By the 1990s, trouble was afoot. A 1994 investigation by The Scotsman uncovered some concerning information. The Glasgow Zoological Society had only 300 members (by contrast their equivalent group in Edinburgh had over 13,000 – each one a financial contributor to the zoo). When the newspaper probed, they found that despite its dire financial circumstances Glasgow Zoological Society was actively rejecting prospective members — apparently at the behest of O’Grady, who talked darkly of “outside forces” gaining control of the zoo.

The following year marked a watershed, both for the zoo and O’Grady. The zoo’s financial problems became a matter of public interest when it emerged it was some £2.3m in debt, and a rescue package was needed to prevent its collapse. This included public funds, which increased scrutiny of the zoo’s management. On a personal level O’Grady’s marriage was breaking down, and he left the family home to live in a caravan on the zoo grounds. In the wake of his separation, O’Grady immersed himself in the zoo 24 hours a day.

Some of his previous acumen seemed to elude O’Grady. The zoo paid the Chipperfield family a five-figure sum for a white tiger, which was both useless from a breeding and conservation perspective and raised the ire of animal rights groups. At around the same time the zoo declined the opportunity to rehome two Sumatran Tigers who could have participated in a breeding scheme. O’Grady’s assertion that the white tiger was “pure showbiz” did little to ameliorate the feelings of his critics.

Even more damaging was the decision to make redundant three carnivore keepers, including the hugely respected Graham Law. Paterson is glowing when he talks about Law, who died in 2020, noting that Law was regarded by his peers as being a “world leader” in the field of animal enrichment.

Paterson says Law’s vision for the zoo was at odds with that of O’Grady; this led to tension between the two, with O’Grady stubbornly refusing to accept Law’s approach as it ran contrary to his own views on animal management. At the subsequent tribunal brought and won by the dismissed keepers it emerged that O’Grady had paid the improbably named CIA private detective agency to conduct surveillance on Law during a period of sick leave.

A plan to redevelop the zoo into a mixed-use leisure complex, dubbed the Glasgow Ark, foundered due to the site’s location on greenbelt land, and concerns among the Council around the viability of the scheme. The plans remained stuck in planning limbo for years, a problem which would again affect the zoo when they attempted to sell off portions of the site in 1999.

The funds this would have generated were desperately needed: as the new millennium dawned, the zoo faced a succession of setbacks. Chief among these was the decision of Glasgow Council to withdraw a £130,000 grant they provided annually. Financial problems were exacerbated in early 2001 when an outbreak of foot and mouth disease forced the zoo to close for six weeks. This followed hard on the heels of an unexpected tragedy on 28 February of that year: the death of the zoo’s mercurial heart, O’Grady.

Paterson was one of the last people O’Grady spoke to. His boss had been complaining of a severe headache, he tells me, but had still powered through some pre-scheduled media rounds.

“He and I had just finished an STV interview slot,” remembers Paterson. “Afterwards O’Grady retired to his office where he collapsed.” By the time the ambulance arrived to spirit O’Grady to Monklands District General Hospital, he was unconscious. He never woke up again, dying at about 7am on 1 March. He was 54 years old. His passing left a hole at the heart of the zoo. Where O’Grady’s dynamic personality had once been able to paper over cracks, now they were on full display.

O’Grady’s successor, Roger Edwards, a long time employee, who had previously served as the zoo’s education officer and deputy director, would have to face the zoo’s most serious crises yet. By this point, any remaining funds were being used for essential animal wellbeing: food, heat, and medical care. Visitor numbers flatlined and never recovered. The zoo was trapped in a downward spiral. And yet, things somehow got worse.

Bad rep

At the time zoos in the United Kingdom were licensed by local authorities, under the 1981 Zoo Licensing Act. This involved regular inspections, at least once every six years. Glasgow Zoo had undergone an inspection in June 2000, and following the implementation of some recommended measures, a new license was issued in April 2001.

However, a year later an additional inspection took place, following several complaints about the zoo. These complaints were likely the product of an ongoing campaign by a range of animal welfare groups, and subsequent press reporting. Supporters of the zoo suggested that these organisations were making a concerted and coordinated attack on what they saw as a weak target, due to the zoo’s ongoing woes.

Welcome to The Bell. We're Glasgow's new quality newspaper, delivered via email. Join our free mailing list to get two full editions a week: a Monday briefing, full of things to do and bitesize news, straight from the city's streets, and a weekend feature, taking you deep inside your local area.

To get total access to all four of our weekly editions, you can join up as a paying member. We'd love that. But we understand you might want to try before you buy, so click below to sign up for totally free and start getting our special brand of local journalism straight to your inbox today.

Jordi Casamitjana was one of these animal welfare campaigners. A writer and former animal welfare investigator, originally from Catalonia, he worked with groups such as Advocates for Animals and the Born Free Foundation, and visited Glasgow Zoo twice in the early 2000s. He recalls his second visit in 2002: “normally (when visiting a zoo) two or three things catch your attention. At Glasgow there were so many […] it was obvious to me this zoo could not exist much longer.” Casamitjana says the enclosures were so decayed that they posed a risk both to animals and visitors. Infrastructure was notably disintegrating and animals showed signs of stress and depression.

The results of the council’s inspection were seized on by the animal rights groups. Along with their own observations and reports it painted a picture of a zoo in a state of physical collapse.

Of greatest concern was site security. Over the preceding years numerous break-ins had occurred due to the zoo’s decrepit fencing system. These had initially resulted in acts of petty vandalism, however on two occasions zoo animals were stolen: in February 2002 thieves gained access to the tropical house, which was in a dire state, and stole two snakes. Weeks later, a similar incursion resulted in the theft of a male Timneh African Grey Parrot. Its distraught mate would die shortly afterwards, as well as a roost of four chicks that had been forcibly abandoned.

What was harder to pin down was concrete evidence of animal welfare issues. Animal welfare groups observed lots of behaviour of possible concern. A frequently cited example in the reports written by Casamitjana was animals, including several of the big cats, pacing the boundaries of their enclosure, in what was described as “frustrated territorial prowling”, often a sign of stress in animals.

Over-grooming was another possible indication of stress, which was seen in some of the birds and primates. Paterson strongly rejected these claims, saying “the level of knowledge and care ensured the animals were always well looked after …to be accused of not doing the job that you love and are qualified to do is very hurtful.” This is apparently borne out by the results of a separate report, by the SSPCA, published weeks before the zoo’s closure which noted no animal welfare concerns and praised the institution’s staff for their work in such straitened circumstances.

The legislative landscape was also not favourable. There had been a noticeable shift in the previously sympathetic attitude of the council. Meetings became combative, apparently not helped by new manager Edwards’ approach, which was characterised as inflexible. With such a relationship there was little chance of funding being reinstated and the zoo was subject to much greater and more critical scrutiny from the council. Casamitjana noted that successful zoos are typically adept at hiding issues, however this usually requires both effective management and investment, both of which were lacking at Glasgow by this point.

Edwards’ approach was also unpopular with the staff. Keepers were not kept apprised of the unfolding situation, were shut out of meetings with the zoological society and were concerned that the zoo was spending large sums of money retaining a PR consultancy, while the declining condition of the zoo facilities and staff shortages remained unaddressed.

Casamitjana recalls that by the time of his 2002 visit the zoo was noticeably deserted, with very few people about, either staff or customers. As he explains, “when a zoo is struggling a critical point is reached when the momentum becomes unstoppable. Everything goes wrong, more and more stories appear in the media until the zoo itself becomes the story.” This, in turn, deters further visitors.

Behind the scenes, a last desperate attempt had been made to save the zoo. Having been blocked from joining and supporting the Zoological Society, former keeper and nemesis of Richard O’Grady, Graham Law, along with Professor Roger Downie, a senior academic at Glasgow University, had reached out to Paterson to discuss the possibility of wresting control of the zoo away from the committee of the Zoological Society, who they characterised as the “tea and biscuit club”, a closed shop who talked a lot but did precious little to arrest the zoo’s decline.

Ultimately both time and money were against this audacious bid, with the discovery of the true scale of the zoo’s debts, which had continued to increase. It became clear it would be impossible to keep the doors open. On 25 August 2003, Glasgow Zoo closed forever.

A scramble then ensued to safely rehome the remaining animals. Despite rumours to the contrary, only one animal needed to be euthanised: Bongo, a 32-year-old Asiatic bear suffering from cancer, who had ironically been placed at the zoo a few years previously by the Born Free Foundation.

By December 2003 homes had been found for the remaining animals. A strange postscript to this story is a series of rumours that circulated of animals remaining at the zoo site years after its closure. An internet story which took on a life of its own suggested that a tiger had lived at the site for two years after the zoo’s closure. This is demonstrably false, however years after the zoo’s closure, prior to the site’s redevelopment, rumours persisted of large unidentified animals in the woods around the derelict zoo.

Ultimately the closure of the zoo came down to two factors: money and management. There was a sharp division between the zoo management, and the people they employed to tend their animals. Paterson characterises the committee and its management team as amateurs who “knew nothing about running a zoo or exotic animal husbandry.” Despite their differing perspectives on the zoo, Casamitjana broadly agrees on this point, noting the zoo’s problems were far from unique but were exacerbated by a lack of management acumen. “There’s only so much the keepers can do when the facilities are that bad,” he concludes.

And so Glasgow Zoo slipped from reality into urban legend. For some, their abiding memory of the latter years was its sad decline. For others there is a tinge of wonder when they recall their first encounter with creatures they’d only previously seen in storybooks, in the most unlikely of places: hidden behind a residential area, just off Baillieston Road.