I’m sitting in a hidden glen in the Campsie Hills when I see them. Five young people, three boys and two girls, standing together in a loose circle. Two are shirtless. Another has a hoodie draped around their shoulders. I look closer. One of the boys is holding a knife. The blade is about six inches long and looks like it has been crafted for hunting. The kind that might be used to skin a rabbit.

I watch him pass it from hand to hand, feeling its weight. He hunkers down and looks over at his mate.

“‘Pass that wood, Kyle?”’

And the atmosphere shifts. The boy holding the knife is Mark, a quiet and compact seventeen year-old, who I know from the G20 youth project in Maryhill. Beside him is Kyle, a tall, kinetic ball of energy, who talks and moves like quicksilver. The pair have been mates since they were kids.

Mark lifts a piece of wood out of the bag and places it upright on the grass. Carefully lining up the sharp edge, he takes a rock and knocks the blade until a shard splinters off, repeating the action until a small pile of kindling gathers on the ground. He scoops it into a tin bowl, using a flint to spark the bundle into flame and looks up at me with a grin.

I’m a criminologist, and have spent the last twenty years of my life studying why young people get involved in violence and streetlife. I cut my teeth in my home city of Glasgow, working with a group of lads whose loyalty to one another – and their area – led them into gang fights, before travelling to Chicago, Hong Kong, Shanghai and London. I started off as an academic researcher, replete with fancy theories and complex statistics, but the further I travelled, the less I felt I knew.

Lately, I’ve taken to podcasting as a way of cutting out background noise and spotlighting the stories that allow direct access to the issues at stake. Armed with little more than a microphone and a strong desire to listen, I embarked on a journey across the UK. It led me from community shops in London where young people flip experiences of exclusion into infectious positivity, to music studios in Manchester where kids diverted from the justice system lay down bars and spoken word poems. It’s called Young Warriors, and I met plenty of them. It’s why I’m in the Campsies today, hanging out with Kyle and Mark.

I first met the pair earlier this year, at Bearsden ski club, in Glasgow’s leafy west end. They were careering down the slope, cheering each other on with ski poles dangling from their wrists.

The meeting had been arranged by G20 Youth Project, a Maryhill based organisation which provides young people who’ve experienced disadvantage with everything from access to the arts, to mentoring and work opportunities. Kyle bounded over, fresh from the run, and began telling me about the first time he met Emily Cutts, now director of G20. He was just eleven years old. A group of them were hanging about in a patch of local land called The Children’s Wood. Cutts had heard about some concerns, and came over to introduce herself. She surprised the group. Instead of telling them off, Cutts asked them what they wanted. Outdoor adventures, it turned out. Kyle loved being out in nature, taking risks. Cutts made it happen.

“We’d have a wee fire, put the hammocks up, marshmallows. And then we just started doing bigger stuff,” says Kyle, eyes wide with excitement. “About four years ago, we went fishing, caught a massive fish.” When I meet them, Kyle and Mark have just completed the Three Peaks Challenge — climbing the three highest mountains — in three days. “We've done loads of stuff”, he continued. “And we’ve loads more to do.”

Welcome to The Bell. We're Glasgow's new quality newspaper, delivered via email. Join our free mailing list to get two full editions a week: a Monday briefing, full of things to do and bitesize news, straight from Brum's streets, and a weekend feature, taking you deep inside your city and the West Midlands.

To get total access to all four of our weekly editions, you can join up as a paying member. We'd love that. But we understand you might want to try before you buy, so click below to sign up for totally free and start getting our special brand of local journalism straight to your inbox today.

I ask him what the outdoors does for him. He answers without pause. “I don’t like being indoors. I get on a lot better when I’m outdoors doing stuff.” The alternative, he tells me, is too easy to imagine. “We would probably be doing other stuff”, he says with a knowing look. “Stuff that you don’t want to be doing.”

I know the stuff he means. I’d seen it too many times before, in Glasgow and cities around the world. The lure of the streets, the mayhem, an income, a reputation — the seduction of a weapon. And it seldom ends well.

Out here on the mountain, with the dappled morning sun breaking through the trees and spilling onto a quiet pool, the violence of the streets feels far away. The boys are calm and focused. Kyle fills a fire kettle and places it on top of flames. Despite the heat, he’s making hot chocolate. The knife lies nearby, neatly placed back in its holster.

A reputation entrenches

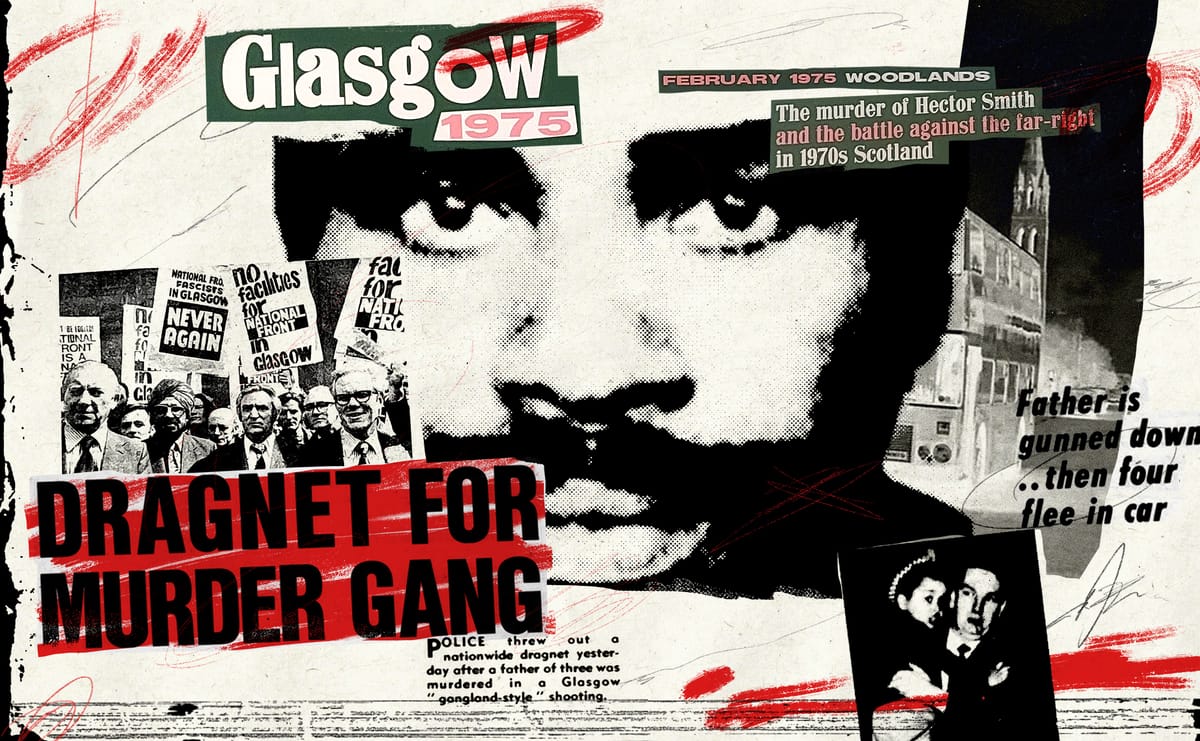

In 1973, a teacher from an ‘approved’ school for young offenders published a book called A Glasgow Gang Observed, under the name James Patrick. The Maryhill boys that Patrick meets – not unlike Kyle and Mark – are bored and restless. They spend their days on the streets, killing time until the mayhem of the weekend, when gang fights, armed with knives and razor blades, break the drudgery. The book follows Patrick as he swaps his teaching attire for a well-cut suit, trying to keep up with the gang as they run riot through smoke-filled pubs, strobed dance-halls, and rain-soaked streets.

Patrick’s method, called ‘covert ethnography’, was highly controversial — verging on unethical. He followed the group round without asking, reporting on their lives without permission. The name James Patrick is a pseudonym, protecting the author from reprisals.

Research methods may have changed in the fifty years since Patrick’s study but the issues that prompted fights among the young team haven’t gone away. He argued that gang violence shows “in the starkest possible way” that “poverty, inferior education…and a steadily deteriorating economic situation all combine to produce feelings of frustration, rage and powerlessness” (p.170).

After leaving the slopes with Kyle and Mark, I join Emily Cutts at the G20 base to learn about how they try to combat these feelings through wraparound support and trauma-based therapy.

The hub is an immediately welcoming space. A reception desk leads into the tables of a community café — Café Hope — with rooms opening into a beauty salon and a therapy room. Green plants and motivational messages — ‘Not impossible: I’m Possible’ — cover every surface. The smell of woodfired pizza fills the air.

We settle down in a room next to the café. Cutts is smiling yet unflappable as members of the G20 community pop in and out. Eventually the hubbub quiets and she reflects back on how the project has grown from its beginnings as an outdoor community space called The Children’s Wood in 2012, to the base where we now sit — combining social enterprise, a youth club, and a growing line in outdoor education.

“We hadn’t realised how bad it was until we met the young people”, she recalls. “There was no safe space for them. A lack of opportunity and investment. They were just hanging about the street, a lot of normalised violence, normalised drug use.” Initially they were working with small groups, meeting them where they were on the land, but realised quickly that more was needed.

Back in 2012, when Emily was meeting this group for the first time, Glasgow was starting to swap its ‘No Mean City’ reputation as ‘murder capital of Europe’ to one of violence reduction. Instead of media headlines depicting a city of ‘booze and blades’, stories of successful interventions started to emerge. At the same time, police statistics showed marked reductions, including a stark decline in violence involving young people. Gang fights were happening less, and knife carrying was less common. How did this happen?

Sea change

For the last four years, I’ve been leading a study trying to answer that question. Nearly 200 people were interviewed, from youth workers to senior police, community activists, and a former First Minister. These accompanied huge swathes of other data. While the reasons for the reduction were complex, the leadership of Scotland’s Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) featured in every conversation. We quickly lost count of the number of people who could quote key phrases used by the VRU — ‘proceed until apprehended’, ‘violence is preventable’ — and point to ways that they had turned these ideas into practice.

Emily Cutts is one of those people. She quotes John Carnochan, a founding director of the VRU. “Start where you are. Do what you can. Use what you have.”

Cutts recognised a contrast in young people’s behaviour when out in nature compared to the local streets. She recounts a story of a young person who was causing trouble in the community, throwing bricks at windows, but among the wild green space of The Children’s Wood “they were playing hide and seek, just climbing trees, having fun. You could almost see the stress levels reduce.”

Kyle is another prime example, Cutts tells me. “He really struggled at school, but outdoors, he's a completely different person. When you take him up a hill, he's perfectly behaved, loves it, gets a real sense of joy from the outdoors, you can see it.”

I can sense the impact that the work has on Cutts and ask what lessons the kids have taught her. She starts to speak, but is immediately choked by tears. “I don’t want to get upset. But some of the stuff the young people had to go through is really hard, really difficult.” When she continues, her voice is now full of resolve. “And they share stuff with you that you’d never repeat to anybody. Yet they still have a lot of resilience, and they’re very kind. If they feel strongly about you, they would do anything for you.”

Getting behind the stereotypes and trying to meet people where they are is one of G20’s main missions. “I think we judge people so quickly and we don't get to know them or look beyond how people look with a hoodie up,” Cutts says. “People instantly feel fearful. But what they might not realise is that person in that hoodie might be more scared than you are and that's why they've got their hoodie up.”

I notice then that Cutts herself is wearing a hoodie, the G20 logo front and centre. It’s tough work, she tells me, but if we don’t do it, who will?

New stories

Outside the old headquarters of Strathclyde Police, now a trendy hotel, I meet Karyn McCluskey, former Director of the VRU (and now Director of Community Justice Scotland). It’s October and although the sun is out, it’s freezing. We sit on angular stone blocks, part of the landscaped redesign, and laugh about the changes to the area. McCluskey realised early that a different story was required if Glasgow was to find a way to reinvent its reputation for violence.

One of her first realisations, she tells me, was that the problem of violence was not unique to the city. She spent time in Boston, Chicago and New York with young men involved in gangs.

“I realised that they were exactly the same as us,” she says. “I know they look different. Big guys, you know, the white tees and the cargo pants. But they were exactly the same. It was all the drivers that we know about, poverty and lack of aspiration and lack of hope, and all the trauma and drugs and everything else growing up. And they wanted the same thing. They wanted to feel safe.”

And just as the problems were global, so too were the solutions. The VRU took policies from the United States and brought them to Scotland. The Community Initiative to Reduce Violence, a city-wide ‘call-in’ that brought young people into Glasgow High Court for an impactful call to stop the violence. Or Street and Arrow, a social enterprise based on LA’s Homeboy Industries, offering young people routes out of the streets to paid employment.

Running alongside this work was a raft of local, grassroots community work doing the hard, long-term graft with young people – from the FARE project in Easterhouse to PEEK in Dalmarnock – and independent innovations happening across schools, hospitals, and youth justice settings.

But more recently rates of violence in Scotland have started increasing again. Just this week, the First Minister John Swinney hosted a summit for leaders and youth groups in the wake of a series of fatal stabbings involving young people.

In our study, we found that some of the drivers of violence were unchanged since James Patrick’s time — exclusion, frustration, powerlessness — but we also heard of new fears around the role of social media and the impact of lockdown on mental health. One social worker told us that “instead of worrying about them fighting on a Friday night, Saturday night, I worry about them self harming all the time, every night.”

I ask Karyn what lessons from the past we need to bring to bear on the present.

“You know what I’ve learned after all this time? There is no substitute for a skilled, empathetic practitioner. Somebody who genuinely listens to people, who talks to them to understand and asks: ‘what are you good at?’”

For Karyn, it’s in places like G20 where change is happening. It’s places like that, she says, where “lives are transformed, families and kids have a different outcome, and you can’t get better than that.”

Talking for themselves

A week after the release of the podcast, I find myself in a BBC Scotland studio with Emily Cutts and Mark. Less than a week earlier, at the launch event, Mark was sunk into a chair at the back. The limelight was not for him.

Today, he is buoyant. We sit in a semi-circle in the studio, speaking into over-sized purple microphones. He can’t quite get his head around the fact that this is going out live. “‘So people can actually hear us right now?”’ he asks incredulously.

The presenter asks Mark about knife crime, and he answers without missing a beat. As he talks, I can see him growing in confidence.

“Knife crime is out there, it’s an everyday thing man. You’ll see it but you can push past it. It’s just life, man. That’s why when Emily asks I always go. She does so much for the whole community. We’re a wee family, we push each other and don’t give up.”

As we leave, the producer calls us over. Listeners have been in touch and he wanted Mark to see their messages:

“Listening to Mark speak has been really interesting. Sounds like a really inspiring young lad who is really trying his best to better himself, make something of himself and also help change the lives of other young adults. Keep going wee man, your smashing it!” reads a text messager from Cupar. “Great to hear from someone like Mark – we need more spaces like G20 for our young people” says Paul in Biggar. “On yersel Mark” says another.

As we walk out, Mark is standing proud, chest stuck out. He is absolutely buzzing, talking earnestly about applying for a job in the Highlands, or becoming a countryside ranger in the Campsies. Cutts is beaming. So am I.

Leaving the cool rationality of research for the hot chaos of podcasting has changed me more than I could ever have imagined. Taking research out into the world, and opening myself up to spontaneity and surprise, has been – as one youth worker from London put it — a rollercoaster of pure joy. And like a rollercoaster, I’ve ended up back where I started, exhilarated and ready for whatever comes next.

A week later, I hear from Cutts again. Kyle has been offered a job in the Highlands of Scotland, working in the outdoors. I wonder, quietly, if he’ll be given a knife.

Listen to Young Warriors wherever you get your podcasts.

Thoughts on today's piece? Let us know in the comments.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.