It was December 1964. John Lynch left his wife and kids on the bus as he stepped off into the gathering dusk on Gorbals Street. He was due a pint. The kids had been to see Santa, and were all bouncing off the walls. Cleland Street seemed a good choice, with four pubs in its short stretch of two tenement blocks. He disappeared into the dark under the railway bridge and was gone.

Hours later, three teenagers found him lying in the backcourt of a now long-demolished tenement. He was dying.

The 43-year-old had been stabbed in the chest and later died in hospital. No one has ever been convicted of his murder.

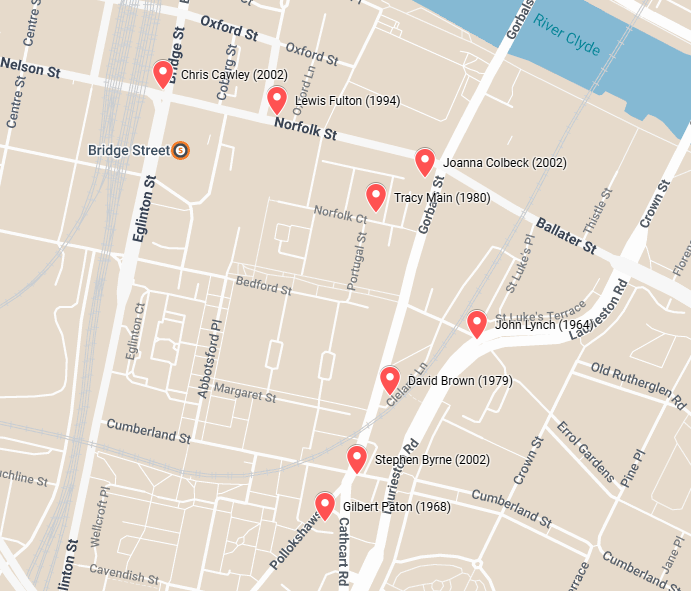

His killing would be the first of eight cases in close geographical proximity spread over 40 years that would go unresolved.

Prior to his death in 1991, the Glaswegian journalist and raconteur Jack House published more than 50 books. The most famous was The Square Mile of Murder in 1961, within which he told the story of four high-profile murders that took place in the relatively genteel environs of Woodlands, Garnethill and Sandyford around the turn of the 20th century. Common among these cases was the privilege of both the victims and perpetrators.

However, at the same time as House’s book was becoming a bestseller, a real square mile of murder was emerging on the other side of the city. It was in the working-class districts of Laurieston and the Gorbals, against the backdrop of tenement housing that was rapidly deteriorating into slums. The killings were all the more notable due to the lack of convictions.

When you place Scotland’s unresolved murders on a map there are a few clusters: Castlemilk is one, the bucolic Perthshire village of Blairgowrie strangely another, but nowhere is there such a tightly packed concentration as the narrow area in the Gorbals and Laurieston surrounding Norfolk Street and Gorbals Street.

James Boyle, 21, was charged with the murder of John Lynch, as well as the attempted murder and robbery of another man that same night. Boyle’s trial was short and farcical. The murder charge relating to the killing of Lynch was dropped on the first day of the trial, after a female witness failed to identify Boyle as one of two men she saw standing over Lynch’s body. A further witness was charged with contempt of court before Boyle was acquitted of all remaining charges. No one has since faced charges relating to the murder.

But the question remains — is there a reason that this part of Glasgow has so many unresolved murders in such a localised area, some geographic X factor that makes murders both more frequent and also less likely to be resolved? Or is it simply a case of the type of misfortune which seems to disproportionately affect less well-off areas? To understand this, it is necessary to look at the various cases.

Sorry to interrupt your Saturday read, folks. But where else would you read an historic exploration of Glasgow's unsolved murders? We firmly think local stories deserve depth, journalistic rigour and thoughtful writing. It's a form of justice, which the victims in this story never got. This is what we do at The Bell.

To make sure you never miss another article from The Bell, why not sign up for free?

Not proven and charges dropped

You can start your walking tour with a pint in the Laurieston Bar. There, in September 2000, bar manager Chris Cawley was stabbed to death in the doorway in front of upwards of 30 witnesses. He had chosen not to serve two highly intoxicated customers, and was attacked as he ushered them from the premises.

Unusually for a violent incident in a pub in Glasgow, none of the witnesses professed to have seen anything, and all 30-plus stories were largely consistent.

Both of his alleged assailants stood trial the following year, however a botched prosecution led to charges being dismissed against one of the perpetrators, while the charges against the second man were found not proven by a jury when his defence placed the blame on his already-acquitted cohort.

Cawley’s family appealed for a public inquiry in vain. They have been part of a group of families who have campaigned vociferously for the abolition of the not proven verdict.

If you were to set out from the Laurieston along Norfolk Street, before turning right down Gorbals Street away from the river, you would pass by the scenes of six further unsolved murders in just 10 minutes. On arriving at the top of Pollokshaws Road, you would see the gable end of the Go Radio studios.

It was in the car park here, when the building still housed the Polmadie Railway Club, that Gilbert Paton was stabbed to death while leaving a dance in the summer of 1968. Paton, then 19, had been there with his fiancee and another couple, however trouble had flared between Paton’s male friend and a group of youths on the dancefloor. Paton was stabbed and died on his way to hospital. A youth was swiftly arrested, but the charges against him were just as swiftly dropped.

In August 2022, in response to a Freedom of Information request, Police Scotland released a list of every unresolved murder they had open at that point. There were more than 1,000 cases listed, spanning the years from 1960 to 2022. Glasgow was disproportionately represented, with more than a third of the cases occurring within the city’s boundaries.

This was a brave bit of accounting by Police Scotland. They listed everything, including cases that would likely never be solved to the point of a conviction occurring.

Among the cases that fall into this category is one of their own.

On 17 June 1994, police were called to a home just off Eglinton Street. A teenage resident had been diagnosed with schizophrenia the previous year, and was showing signs of an acute mental health crisis. He had left the property carrying a large knife.

PC Lewis Fulton was one of a group of officers dispatched to apprehend the youth. By the time Fulton arrived, he had reached Norfolk Street, where he was continuing to behave erratically. Fulton and several other officers confronted him and during the ensuing struggle, Fulton was fatally stabbed.

Fulton’s death led to improvements in standard police equipment, however his killer never spent a day in prison — he was sent to Carstairs State Hospital and then released five years later.

High rises to the high court

The scene of Fulton’s death on Norfolk Street is barely recognisable today. The surrounding area has been the scene of continual change. In the second half of the 19th century, the tenement housing that would dominate the area sprang up as its population was swollen by incomers from elsewhere in Scotland, Ireland and Eastern Europe. The area’s population swelled, to a peak of 90,000 in the years immediately following the second World War.

By the time John Lynch’s killer stalked the area, the Gorbals’ golden era was long past. The tenements were overcrowded and unsanitary, and gaps appeared as buildings were torn down and the population decamped, many to the large housing schemes that were being built on the city’s periphery. As quickly as the population swelled, it dropped: by the end of the sixties as low as 6,000. The area became a byword for crime, poverty and slum conditions.

The new high rises of Norfolk Court loomed over what remained of Gorbals Cross, stripped of its shops and the decorative fountain that sat at the intersection. They had been built in the early 1970s but, by the 1980s, residents of these flats and others complained of social problems and a breakdown in cohesion, as well as issues such as damp and draughts. Nonetheless, in its early years Norfolk Court was seen as a desirable place to stay. Subsequent events would cause many to revise this view.

Tom and Dorothy Main were among the early residents. They lived in a second-floor flat with their 13-year-old daughter Tracy. Both parents worked long hours, and trusted Tracy to get herself out to school each morning. What they didn’t know was that on some days, Tracy chose not to go to school.

5 February 1980 was one such day. Dorothy Main usually returned home first each day, so she was alarmed when she found the front door ajar that afternoon. After summoning a neighbour, they entered the property to find Tracy’s partially clothed body slumped on the living room floor. She had been stabbed repeatedly.

Police soon arrested 43-year-old Thomas Docherty, who had moved on to the same landing as the Mains only six weeks previously. Docherty, who was developmentally disabled, had already gained a reputation in the building for furtive behaviour, earning him the nickname “the Creeper”, and he had been seen watching Tracy while she had helped her mother clean the communal landing.

At trial it emerged that when interviewed, Docherty apparently disclosed information that was not public knowledge and effectively incriminated himself. The only problem was that the detective interviewing Docherty failed to explain his rights at the outset of the interview, which subsequently led to the trial collapsing. His solicitor, the famed Joe Beltrami, was bullish, stating that if the trial had proceeded, he had no doubt he would have won an acquittal, pointing out the lack of physical evidence tying Docherty to the crime scene.

Docherty was, however, guilty in the eyes of the citizens of the Gorbals, and an angry mob awaited him outside the High Court. He was spirited into hiding while authorities weighed what to do with him. He eventually spent time in Carstairs, before being released under a new identity. In subsequent years, rumours would arise frequently that Docherty had returned to Glasgow, but neither determined journalist, nor crazed vigilante has ever tracked him down.

In 2020, Police Scotland launched a renewed appeal for information around the murder of Tracy Main, however the case remains unresolved.

And justice for none

While the slum tenements had been cleared in the preceding years, a residue of squalor remained. Both of Tracy Main’s parents worked in homeless hostels, while the Talbot Centre, a charity dedicated to helping the unhoused, had a hostel on Gorbals Street. In the freezing winter of 1978–79 one of its residents was 43-year-old David Brown. On a frigid January day, he and a group of fellow residents decamped to the railway arches on Gorbals Street. A fire was built and money pooled. One of the group was dispatched to acquire whatever intoxicants they could. The group ended up sharing a mixture of hair lacquer and water.

At some point, a fight broke out. During the fight, David Brown was struck in the head with an iron bar and left on the ground. He was still there two days later, when his body was discovered frozen to the ground. Police would later arrest one of his fellow drinkers, but in court a coherent narrative of the events leading up to Brown’s death was elusive, the memories of the various witnesses being fogged and disorderly, and the judge had no option but to advise the jury to find the accused not guilty.

The woman in the window

By the 1990s, change was afoot once again. The physical issues with the modern flats, coupled with the social problems which were by now pervasive, led to the decision to again redevelop.

Two of the high rises at Norfolk Court remained standing, and one of them would be the site of another unresolved tragedy. On 25 May 2002, two worshippers leaving Glasgow Central Mosque glanced up and saw a figure dangling from a window on the 20th floor of 5 Norfolk Court. The figure, later identified as 28-year-old Joanna Colbeck, released or lost her grip and fell from the window. She died instantly.

The flat from which she had fallen belonged to 38-year-old Rose Broadley, who it was alleged at trial had been Colbeck’s drug supplier and pimp. Broadley was arrested and charged with her murder. At her trial in 2004, the prosecution contended she had pushed or forced Colbeck from the window of her flat. The jury agreed with this.

However, Broadley’s lawyers appealed her conviction and were successful. They highlighted the fact that there was no evidence that had placed Broadley at the window when Colbeck had fallen, and no witnesses had reported seeing anyone else at the window. Joanna Colbeck’s death remains classed as unresolved by Police Scotland. Broadley died in 2017.

Brazen violence

Shortly before the terminus of our earlier walking tour, we passed by one of Glasgow’s most famous Celtic pubs, the Brazen Head, located under a railway bridge at the intersection of Pollokshaws Road, Gorbals Street and Cumberland Street.

During the early hours of 22 July 2002, a regular patron, 36-year-old Stephen Byrne became involved in an altercation in the upstairs nightclub, Durty Nellie’s. The fight spilled into the street and ultimately resulted in Byrne being beaten and stabbed to death. Three men were arrested, including a bouncer at the venue, however ultimately no one faced justice for Byrne’s murder.

Byrne’s murder was the culmination of an escalating pattern of violent incidents apparently linked to the pub. The Brazen Head’s late licence was suspended, and a special meeting of the council’s Licensing Board was convened to discuss revoking its licence entirely. This was ultimately dismissed by the Board, who received a petition with more than 2,000 signatures from the licensee’s lawyers opposing the revocation, as well as letters in support of the pub from two Labour MPs and an MSP.

The licensee, Franco Fraioli, placed the blame elsewhere. “I believe (the violent incidents) are more to do with social problems which have been associated with the Gorbals for years,'' he told The Herald. “What do they expect me to do — walk customers home?”

If you've made it this far down the article, surely you'll enjoy more of our writing? To make sure you never miss another article from The Bell, why not sign up for free?

Even since 2002, the Gorbals and Laurieston have changed radically. The revamped Citizens Theatre opened earlier this year, and it sits across the road from the smart Laurieston Living residential development which occupies the corner of Gorbals Street and Norfolk Street, replacing the finally demolished Norfolk Court.

Some scars remain. Cleland Street still exists in name, but in reality it is little more than a railway underpass and some scrubby ground, in spite of some neat public art by Liz Peden celebrating some of the Gorbals’ famous sons and daughters: the boxer Benny Lynch, the artist Hannah Frank and the detective Allan Pinkerton. Likewise, the railway arches where David Brown died remain an eyesore, in spite of plans to redevelop them put forward in 2019.

Over a 40-year window, eight murders went unresolved in this small patch of Glasgow. While the cases themselves share few commonalities, the geography is significant. The Gorbals and Laurieston are areas with a reputation that precedes them for poverty and social problems. In the field of critical geography, multiple studies have clearly aligned patterns of criminal justice outcomes with socioeconomic disparities — essentially the more prosperous an area is, the more likely its citizens are to see justice. The privations that this particular corner of the Gorbals and Laurieston have undergone over the 20th century and the early years of this century suggest an area primed for misfortune of this type. It can only be hoped that the latest changes and improvements that these areas of Glasgow have seen in the last 20 years will finally end the ills that have plagued them — and also bring to an end this cycle of unresolved killings.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.