When Bob Alston first came from New Jersey to Glasgow in 1971, he was a 24-year-old soldier who had signed up, like his father, to serve in the US army.

As you might expect of a military man, he liked to keep fit — often running six or seven miles from his Woodside home along the Forth & Clyde Canal, which had closed to navigation in 1962. Most of the time, he says, he was the only person in sight. If other joggers appeared, they were invariably male. The “nolly” — as the canal was sometimes known — was not a safe place for women to be alone.

“It was a dump,” Bob says, shaking his head, as we stand on the same towpath today.

Aged 78, the quietly spoken Garden State expat now walks with a very light limp. No more running. But as well as remembering how this part of Glasgow looked 50 years ago, Bob has helped to change it.

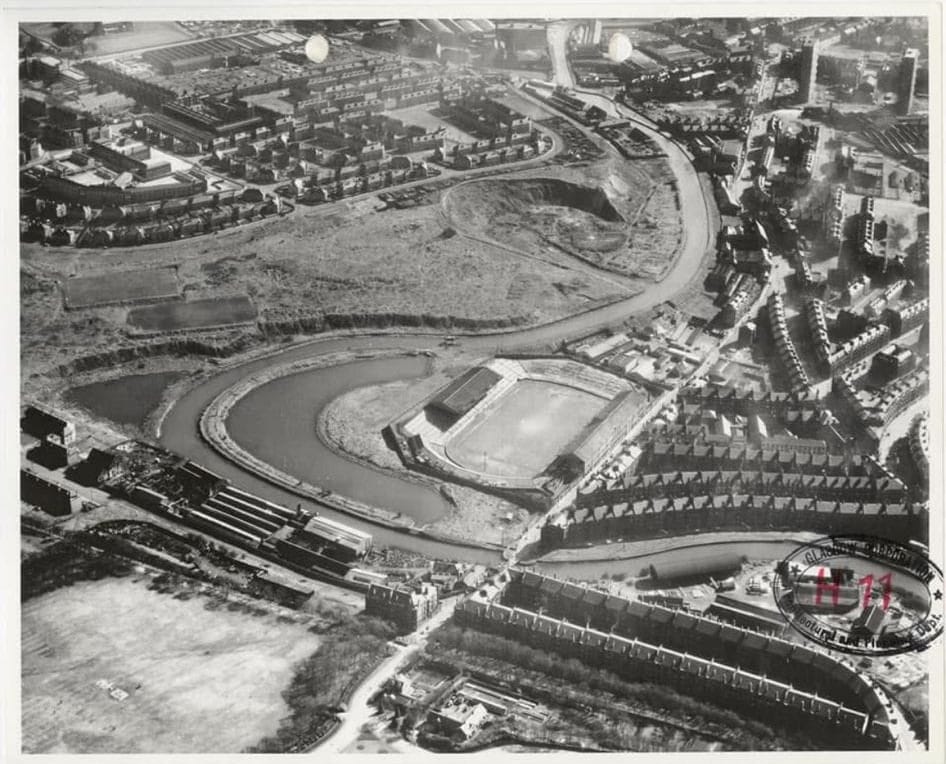

By concentrating on a troubled pocket of canalside land measuring just 6.73 hectares, a group of private, charitable and civic bodies pulled off an urban reversal whose positive effects have radiated outwards. Their focus was the crescent-shaped area between Firhill and Applecross Basins, with Firhill, Maryhill and Woodside to the south of the water and Hamiltonhill and Possilpark to the north. As the crow flies, all these neighbourhoods are close to each other — and to the city centre. But a post-industrial wasteland filled with dead washing machines was piling up between them, and without an easy way to cross the water.

Wandering now into the Claypits — known officially as the Hamiltonhill Claypits Local Nature Reserve — you’ll see Tortoiseshell butterflies, blue tits and woodpigeons flying above fluffy cocksfoot grasses, yellow coltsfoot and reed sweetgrass. Toads soak in pond water. If you stayed long enough you might catch occasional flashes of white-and-grey pigeon feathers flying from the three “doocot” pigeon lofts around the reserve, holdouts of a working-class tradition that is itself ironically under threat of extinction. (Scottish Canals want to phase the doocots off this land — more on this later.)

Seven hundred and forty-one species have been counted here to date, but humans have arguably gained as much as the more rarely spotted lake limpet, otter or water vole.

Hi, welcome to the claypits. And welcome to The Bell. Like Hamiltonhill nature reserve, we are rejuvenating a tired old thing which has fallen on hard times: local journalism.

If you sign up for free, you'll get one Monday Briefing, which is packed full of local news, recommendations, reviews, and events; and you'll get an in-depth weekend read, like this one, which will give you a new perspective on Glasgow. You'll also get a sneak peak of our midweek paid editions, which have local news stuffed into the top which you can see, still for free.

What are you waiting for? Get all this amazing Glasgow journalism in your inbox via the link below.

Century of toxins to natural haven

In the years since the reimagined Claypits opened in 2021, more than three million visits have been counted by automatic stewards in metal fingerposts at the five entrances, according to the Hamiltonhill Claypits LNR Management Group, of which Bob is a trustee and volunteer. Run-down bits of the city have been knitted together, and it is used variously for family “forest school” sessions, science and art classes and people in recovery, among other things. Volunteer litter pickers sweep through every month, finishing with tea and donuts. So, what went right?

First, what went wrong. In the 19th century, when the original claypits were stationed above Applecross Basin, the canal was lined by kilns that fed busy tile and brickmaking businesses. Add in glassworks, ironworks, timber merchants, and a boatyard, brewery, tannery and mine shaft along this canal corridor and there was enough mineral pollution to create a century’s worth of toxicity — contaminated soil and water reeked with high iron content.

After the first world war, a new municipal housing scheme was erected at Hamiltonhill, but by the 1950s the canalside industries had all but faded, and Glasgow newspaper headlines worried that the estate had become a “slum”. Latterly, the sloping canalside land was overgrown with shrubs and trees, inaccessible to walkers, and by reputation pretty drug-fuelled and dangerous, especially at night. Depopulation was also making the area feel sluggish. If you lived in Hamiltonhill, Woodside or Firhill, adjacent to the canal, your health and prospects were apparently as condemned as the soil — in the worst-afflicted 15 per cent of the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation.

In 2015, a partnership between Scottish Canals, its affiliate developer Igloo and Glasgow City Council was agreed to begin exploring regeneration. It came up with a Canal Action Plan which proposed the development of “semi-wild greenspace near the city centre… part of a wider initiative to create a vibrant neighbourhood in North Glasgow.” Around this time Bob, as part of the Woodside community council, was brought in alongside other local reps from the surrounding neighbourhoods to discuss the project. In 2016, the space was given nature reserve status by the council — the only such example within Glasgow city centre.

The council, in its 2018 masterplan for regenerating Hamiltonhill, noted that the post-industrial community suffered "complex" social and economic issues, and “unemployment, depopulation, poverty and ill health touch many in the area”. But it also pointed out that vacant and derelict land made up almost a fifth of the land area, a large chunk of that being where the Claypits nature reserve now stands.

Funding from the EU, Nature Scotland and NHS Glasgow, and some ongoing pots from NGOs, put together a £10m-plus plan. When work finally began in 2020, Bob says, “the first few months were spent clearing out old TVs and cars from the canal”. Then Covid-19 struck, and the contractors carried on alone. (Perhaps, he thinks, planting some of the trees too close together.)

In the early 2000s, Bob says, Scottish Canals had investigated housebuilding above the canal banks, with potentially prized views onto the city. But the risks from pollution and nearby electricity pylons ruled that possibility out. “This was the only thing they could do,” Bob says. “But we ended up with this lovely space.”

The greater crested Tennents-necker

On the September day when Bob and I meet, walkers, runners, buggies and students pass in healthy numbers on Garscube Bridge, a new crossing over the once no-go canal waters. This £3-million piece of engineering opened in 2021 with much bigger ambitions than to simply connect two banks of the canal. It connected whole neighbourhoods to the south and north — creating a shortcut that opened up the city centre on foot, and relegated longwinded bus journeys. “All these communities were cut off,” says Julieanne Levett, of the Hamiltonhill Local Nature Reserve Management Group. Boats can also now pass through the bridge’s modern lock system, brought back to the water by Scottish Canals, which began pumping millions into reopening the Forth & Clyde around the millennium.

On such a gorgeous autumnal day, lots of people are using the bridge and basking in the sun inside the reserve. A couple of lads are peacefully necking cans of Tennents near the entrance, and apart from a spot of graffiti, it’s a clean, welcoming space.

Come night time, Bob says, infrared cameras pick up roe deer crossing the bridge and disappearing into the woods. Last year, two new species were recorded — the Orache moth and a fungi called Haw Goblet. A large maple tree is very popular with bats.

We follow the blond-gravel walkways up to what used to be known as Old Jack’s Mountain, now rechristened by Scottish Canals as The Viewing Point, looking west on tenement crescents, church spires and onwards in clear skies towards the coast.

At the viewing spot we bump into fifty-something Jasna Memic, who walks up from Hyndland on sunny days to make the most of the warmed-up slabs of stone dredged from the canal and repurposed as benches. “I love this space — in the middle of Glasgow, it’s such a privilege. I see amazing things — ” she gets out her phone to show us, “female roe deer with two babies!”

The endangered doomen

“How ya doing, big guy?” says a dog walker to Bob as we pass on one of the northern paths, up towards the Firhill Basin. It’s the weather for good moods, but also, everyone seems to know Bob.

At one of the other entrances near Ellesmere Street, a map by Glasgow artist Mitch Miller captures the history of the Claypits and surrounding streets in an annotated diagram. Bob is at the centre of it, drawn with a trolley, fixing things. Even as we walk, he sees jobs to do: the plastic casings around the saplings need to be taken off soon. They were there to protect the sweet-tasting young bark from being eaten by the small but growing population of deer.

The charity manages the space on behalf of joint landowner Scottish Canals (the council also owns some of the area), but they don’t yet have a land agreement in place. That puts them in an awkward position. Part of the problem seems to be a turnover of staff at Scottish Canals — “it’s the fourth group of people in charge,” Bob says. “But we’re making progress.”

One of the biggest disagreements, according to HCLNR, has been over the fate of three doocots dotted around the reserve. These pigeon-keeping dwellings, a famed part of Glasgow working-class tradition, are tucked away from the main drag of the reserve. Bob takes me to see one that blew down in a recent storm, and has been thriftily patched back together. We’re standing outside it, listening to the birds cooing, when James McIver suddenly steps out from inside. This “dooman” has been keeping pigeons on this land for more than 30 years, and lives over near the Possilpark chapel off Saracen Street, near where he was born. He’s 76 now, but “I’ve had a doocot since I was 7,” he says. “We had them in the hoose, making them out of boxes and old pram hoods, string it up.”

He says flattering things about the newly regenerated Claypits. “Everybody likes it, and they’re not scared to come through it anymore. A woman came to my shed the other day and asked for tea!” James’s shed is on a hard standing a few yards from the doocot, which he built himself from the thin metal used to put up billboards “five pound a sheet.” He also built the shed, in corrugated iron, and has kitted it out with a two-seater sofa, chest of drawers, a radio, two-ring cooker and toaster. There’s a framed photo of one of the other late doomen who, like McIver still does, visited his pigeons every day.

The problem, Bob says, is that Scottish Canals wants the doocots gone. Their initial wish, he says, was to evict the doomen summarily once regeneration got underway. Bob’s management group pushed back, and eventually, he says, it was agreed that the lofts could stay put for as long as their keepers were alive. The three left will, in theory, be the last to let their lead-grey and white-feathered birds out to breed, in these Glasgow treetops at least. I ask Scottish Canals why this approach is being taken, but they respond stonily — only to say that they have “no record of any formal agreement in place”.

This could spell good or bad news for the doomen and their birds. Scottish Canals confirms a land use agreement for the Claypits is still “in negotiation” with HCLNR Management Group, so its position could change. It’s a dark bass note in the more utopian mood of the wider project. Waiting for the doomen to die doesn’t seem to fit with the idea of a place that was supposed to bring the surrounding community with it.

Hopefully, this newly rejuvenated space can keep some of the oldest living traditions going, as well as bringing back flora and fauna not seen for decades. “Whatever is here is ours. We keep the paths clear,” Bob says, “and leave nature to it.”

Thanks for reading Natalie's story. To make sure you never miss another cracking weekend read, you can sign up by clicking below. By the way, it's totally free to do so.