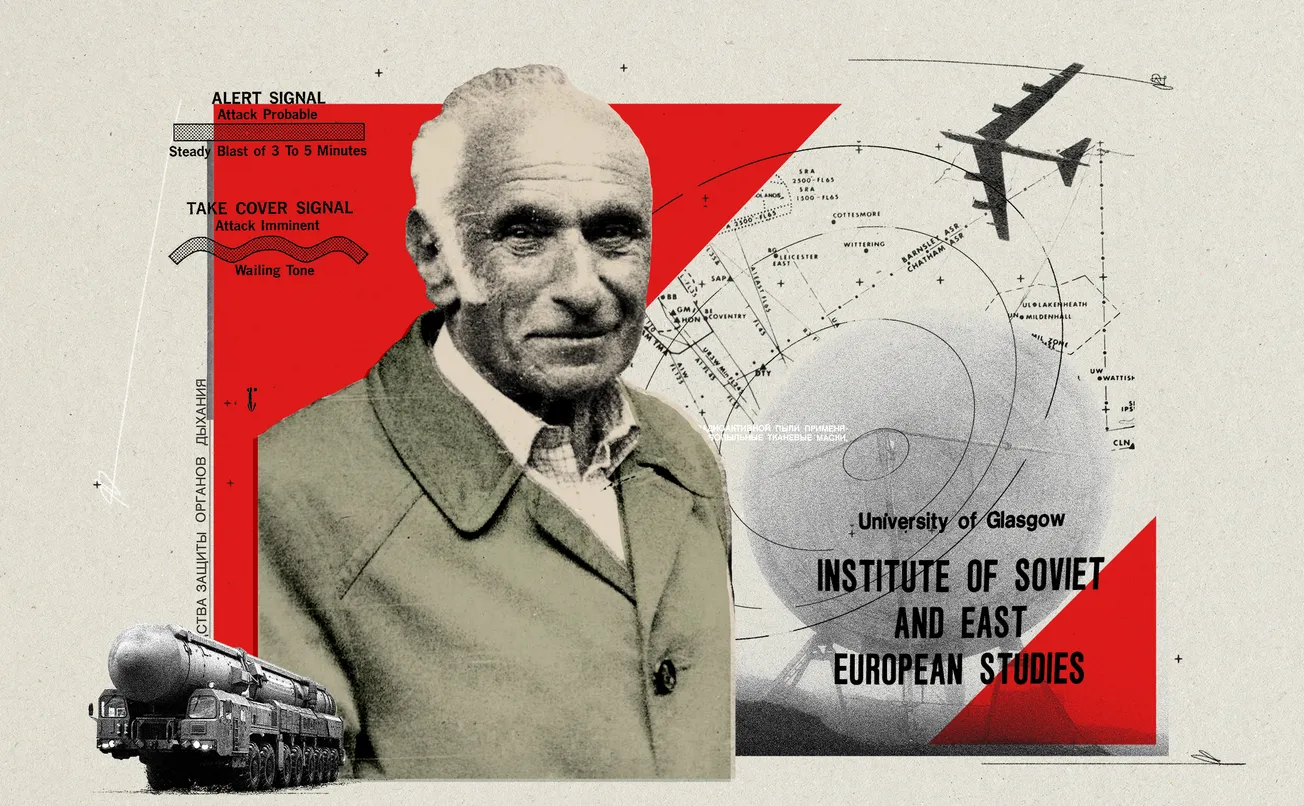

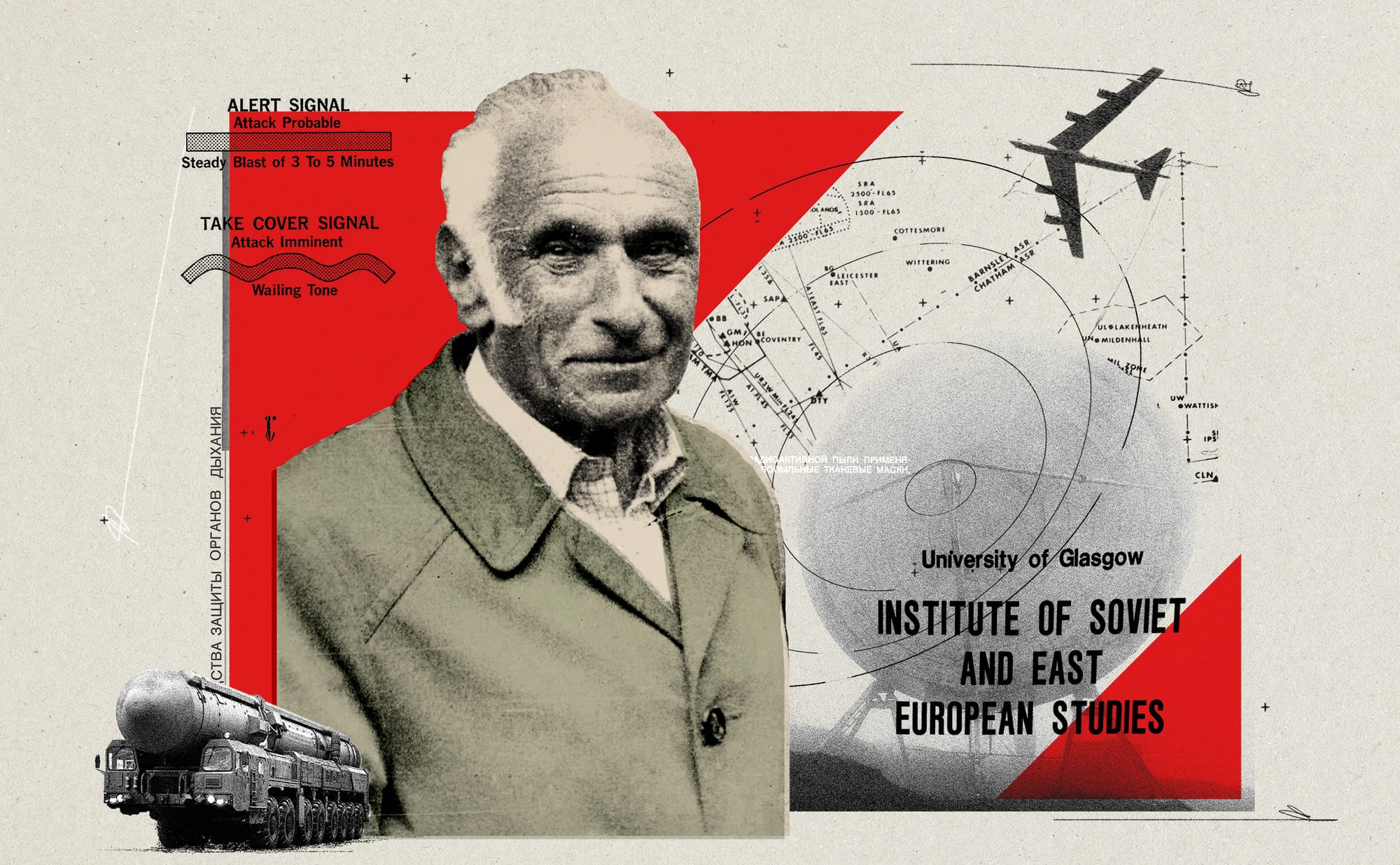

Here’s something you may not know about Scotland’s largest city: at the height of the Cold War, as Moscow and Washington diced with nuclear death, Glasgow led the world in the study of all things Soviet — Soviet politics, Soviet economics, and Soviet society. The reason for Glasgow’s exalted status during this pivotal period in human history was an academic by the name of Alec Nove. Nove’s story is extraordinary. The multilingual son of an exiled Menshevik, he settled in Glasgow in the early 1960s and spent the next three decades of his life channeling, with a peculiar kind of prophetic brilliance, into the heart of Russian communism.

Such was the extent of Nove’s reputation that he was once greeted by one extremely high-ranking member of the Soviet Communist Party with the words: “So you’re the man who knows more about the Soviet economy than I do!” The comrade in question was Mikhail Gorbachev. “He was enormously chuffed by that,” Nove’s son, Charles, tells me when we speak after Christmas. “I remember him having a beaming smile on his face. It was a special moment to have the new Russian leader acknowledge him by name.”

Nove’s journey to Glasgow was circuitous. Born Alexander Novakovsky in St Petersburg in 1915, his father, Jacob, was a liberal political activist in pre-revolutionary Russia. In 1922, after the overthrow of the Tsars, Jacob, who had Jewish-Ukrainian roots, was arrested by the new Bolshevik authorities and presented with a choice: relocate to Siberia on a permanent basis or exit the country forever. Jacob chose the latter and, shortly after, fled with his wife and young son to London. In 1936, at the age of 21, Alec changed his second name from Novakovsky to Nove. “There were some cousins who had arrived [into Britain] earlier,” Charles says. “They had shortened their name to Nove, so he decided to follow suit.”

As soon as he reached the UK, Nove received what can only be described as an accelerated scholarship in Britishness. He was educated at the liberal, private King Alfred School in North London, then completed a degree in economics at the LSE. During World War Two, he served in British military intelligence. After the war, he found a job at the British Board of Trade. It was here, in-between devouring journals on Soviet economic strategy, that Nove learned about price controls and exports targets — vital experience for his later work as an economist.

The move north

In 1951, Nove married Irene MacPherson, a Glaswegian woman whom he had met at the Board of Trade, and secured a two-year secondment from Whitehall to the Department of Soviet Studies at the University of Glasgow. Charles was born in 1960. There were two more sons, David and Perry, from a previous marriage. Nove’s ties to Glasgow crystallised in 1963 when he was made Director of the University’s Soviet Department, recently renamed as the Institute of Soviet and East European Studies (ISEES). In the years to come, Nove would transform the Institute into a global powerhouse of analysis and insight, a wellspring of information about life in the Soviet Union that rivalled, and frequently outranked, equivalent schools in more prestigious locales across England, Europe, and the US.

Welcome to The Bell, we're delighted you're reading Jamie Maxwell's tale of Glasgow's cold war hero. All of our articles are delivered entirely by email, and if you sign up to our mailing list, you get two totally free editions of The Bell every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece.

We're trying to give Glasgow the journalism it deserves, and you can sign up to it for free. Need extra convincing? Once you're done with Jamie's article, try Natalie Whittle's ode to our Chateauneuf-du-tap.

In part, the Institute’s reputation stemmed from its in-house journal, Soviet Studies, which published ground-breaking essays on everything from Soviet agriculture — a specialism of Nove’s — to the status of minority languages in the Soviet education system. Soviet Studies predated Nove’s arrival at Glasgow and Russian had been taught at the University for decades. But it was under Nove’s watch that the journal’s reach went global.

According to Professor Richard Berry, who was a student of Nove’s in the 1980s and runs the Institute today, Soviet Studies was read not just by academics in the West but by policymakers in Moscow and Beijing, too. “The journal was translated for communist elites so they could see what we in the West were thinking,” Berry says when we meet at Glasgow University on a damp December morning, mist hanging heavy over the campus. “In Russia, they had a team of people who did that.”

Nove ran the Institute, marked by a distinctive red and white sign, out of an old sandstone building on Southpark Terrace next to the University’s Catholic Chaplaincy Office. The intellectual culture he fostered was intense. Every Wednesday afternoon, in a wood-panelled seminar room, a discussion group convened at which rival factions — Trotskyites, social democrats, and conservatives — debated developments in Soviet politics.

The seminars were not always civil. “It was pretty fierce stuff,” Berry remembers. “The debates were heated, but the level was exceptionally high and everyone was up to speed on the latest theories and writings.” Nove, a social democrat, sometimes grew impatient with his interlocutors. “He would get quite red and kind of lose it,” Berry says. “He was very passionate. He gesticulated when he spoke. Nove was not a quiet man.” The Institute’s standing was bolstered further by the presence of other Russia luminaries like Roger Clarke, the editor of Soviet Studies, and Professor Hillel Ticktin, a leading European Marxist.

Politically, Nove was progressive, a critic of the Soviet Union but not committed on an ideological level to its destruction. As an economist, he could see early on that the centralised Soviet economy was suffering from systemic problems of pricing and over-production — in effect, an inbuilt imbalance of supply and demand. Between 1961 and 1993, he wrote a series of books — including The Soviet Economy (1961), Political Economy and Soviet Socialism (1979), and The Economics of Feasible Socialism (1983) — that became canon on the structural failures of the Soviet experiment.

Nove stood out for the sheer scale of his learning. He was an expert not just on Soviet economics but on Soviet culture in the broadest sense. He read Russian novels and understood Russian society. He travelled in Eastern Europe and moved in Sovietologicial circles, lecturing everywhere from Paris and Stockholm to Kansas and New York City. Crucially, Nove spoke Russian, the language of his homeland, with a fluency that most Western academics could not match. To his excellent Russian he later added French, German, and some Spanish and Italian. The Oxford University historian Archie Brown, another world-leading Soviet specialist, was a friend of Nove’s and taught alongside him at Glasgow between 1964 and 1971. “Everywhere Alec went he acquired fresh insights and was able to synthesise all the additions to his knowledge,” Brown told me. “I learned more about the Soviet economic system and relations between party and state economic institutions from Alec than from any other economist.”

Thriving in Glasgow, blacklisted in Moscow

In the early 1970s, in Russia, Nove’s fame shaded into notoriety. Together with several other British academics, and in blanket retaliation for the expulsion of a Soviet spy cell from Britain, he was placed on a KGB blacklist and banned from entering the USSR. The Communist Party newspaper Pravda later attacked his department as “the Anti-Soviet Institute of Glasgow University.” Nove was proud of the Pravda epithet but found being barred from Russia — again — painful. “It was a source of great sadness to him,” Charles told me, wistfully. “My father always retained great affection for Russia and great hopes for Russia.”

Charles, now a prominent radio presenter, remembers growing up in the West End, in a high-ceilinged flat on Hamilton Drive that played host to an endless stream of ambassadors, intellectuals, and activists, many of them dissidents from the Eastern Bloc. There were no formalities in the Nove household. “My father was very hospitable,” Charles asserts. “If you stayed at the house, you were treated as family. Famously, at dinner, he would grab bread from the bread basket and throw it down the table at the visitor.”

Nove’s Hamilton Drive Hogmanay parties were legendary — and had a habit of undoing Glasgow’s otherwise staid academic elites. According to Charles, on one occasion, an eminent professor was found the following morning, “feet sticking out from under the dining room table, where he'd nodded off.” When something significant happened in the Soviet Union, Nove would be invited to comment in the media. He often took his youngest son down to the BBC’s studio on Queen Margaret Drive — a short walk from the flat — to watch as he recorded TV interviews and radio segments. Charles caught a taste for broadcast.

By the early 1980s, the Cold War was approaching its climax. In 1979, the Brezhnev regime, decaying and indebted, invaded Afghanistan. In 1980, Ronald Reagan, a hardline anti-communist, was elected president of the United States. Nuclear tensions were intensifying and relations between Moscow and the West getting worse. Margaret Thatcher entered Downing Street in 1979 as a radical opponent of Soviet communism, a system she believed was “bent on world domination.” However, an encounter with Nove early on in her second term helped soften her hostility towards Russia and shift the trajectory of Britain’s Soviet strategy.

Nove was one of eight specialists invited to participate in a seminar on the Soviet Union staged by Thatcher at Chequers in September 1983. The group, which included Archie Brown, wrote papers that were read and annotated by the prime minister, the foreign secretary, Geoffrey Howe, and the defence secretary, Michael Heseltine, in advance. Nove, Brown and the other experts advised against a policy of isolating the USSR. Instead, they argued, to promote “change from within”, the West should engage on all levels with Soviet society, “from dissidents to General Secretaries.” “We were allowed ten minutes each before questions from the government side,” Brown told me. “Mrs Thatcher took quite a lot of notes from Alec’s paper.” The seminar lasted six hours and was later described by Sir Anthony Parsons, an adviser to Thatcher, as having “changed British foreign policy” by opening a new era of engagement with Russia and the communist states of Central and Eastern Europe.

The official invitation to Gorbachev to visit Britain for the first time also had its origins in that seminar. Gorbachev arrived in London in December 1984. The night before the meeting, Nove and Brown were among four specialists summoned to Downing Street to brief Thatcher again on Soviet affairs. Professor Brown recalls the event culminating in true Novian style: “The evening over, the group had only just begun to descend the staircase at Downing Street when Alec said, loudly and clearly, ‘I just wish she would consult us on domestic policy as well’.”

Nove was born in Russia and spoke with a posh English accent. But he was an honorary Scot. He adored Glasgow and loved taking long walks down the Clyde. He attended the Citizens Theatre and became a patron of Scottish Opera. During the summers, Nove and Irene would often decamp to the Western Isles with the kids. Nove could have left Scotland for a more illustrious posting elsewhere but his attachment to Glasgow, his adopted hometown, the base from which he studied and explored the Soviet world, ran deep. “Alec loved the fact that Glasgow had all these parks,” Berry tells me. “He was a great supporter of social housing. He felt that there was a kind of civic pride here.”

Nove stood down as director of ISEES in 1982 but kept working — writing, lecturing, and travelling — relentlessly. “He was in the building basically every day,” Berry says. Eventually, his name was removed from the KGB blacklist and his second Russian exile came to an end. Nove returned to Russia several times after Gorbachev, the great liberal reformer (and Nove admirer), was appointed Soviet General Secretary in 1985.

Six years later, Gorbachev resigned, defeated by the collapse of the Soviet Union. Nove fretted about the fate of his birth country. During a guest lecture at Columbia University in 1993, he remarked: “The demoralised and confused Russian people ask yet again the eternal question kto vinovat (who is to blame)?” It would be one of his last public appearances. In May 1994, Nove died of a heart attack while on holiday in Norway with Irene. His final words were characteristic: “I’m perfectly alright, you know.” He was 78.

Today, under Berry, Glasgow’s Institute is thriving, as is its landmark journal, although both have since been renamed. The Institute is now called the Centre for Russian, Central, and East European Studies. The journal is called Europe-Asia Studies. More than half a century after Nove’s arrival in the West End, Glasgow remains a global academic authority on Soviet, and post-Soviet, politics. A few years ago, when the Centre relocated from one side of Southpark Terrace to the other, Berry rescued the Institute’s iconic red and white sign from a skip. It now sits in his office beneath a selection of Nove’s books. In the adjoining seminar space stands a mottled bust of Nove made by Benno Schotz, the famous Estonian-born Glasgow sculptor. The bust beams out across the room. “A tour de force was Alec,” Berry says, with a smile.“If you met him, you weren't likely to forget him.”

Thanks for reading about Alec Nove. If Jamie's article piqued your interest, why not sign up to our completely free mailing list. Every week, you'll get two totally free editions: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.