In rail terms, Glasgow is a giant. Its population of more than 600,000 — and wider city region population of nearly 2 million — are kept moving by the UK's best suburban rail network outside of London. This includes several lines and countless stations, bolstered by the diminutive but noble little Subway that loops around the west of the city centre. The network is almost fully electrified, with electric trains expected to be running to East Kilbride by the end of next year and the Maryhill line to follow (eventually).

But before we start patting ourselves on the back, we need a reality check: Glasgow’s rail network faces serious problems. Before we look at what they are, and how to fix them, let’s first get a grip on how things look today.

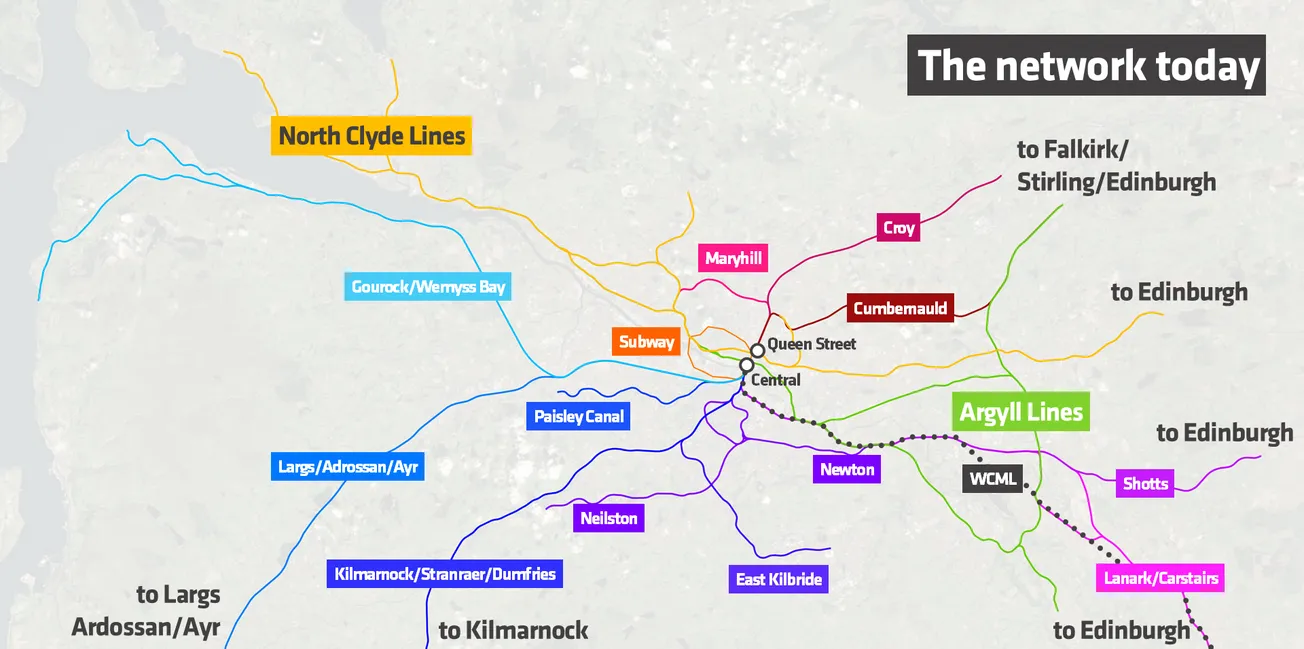

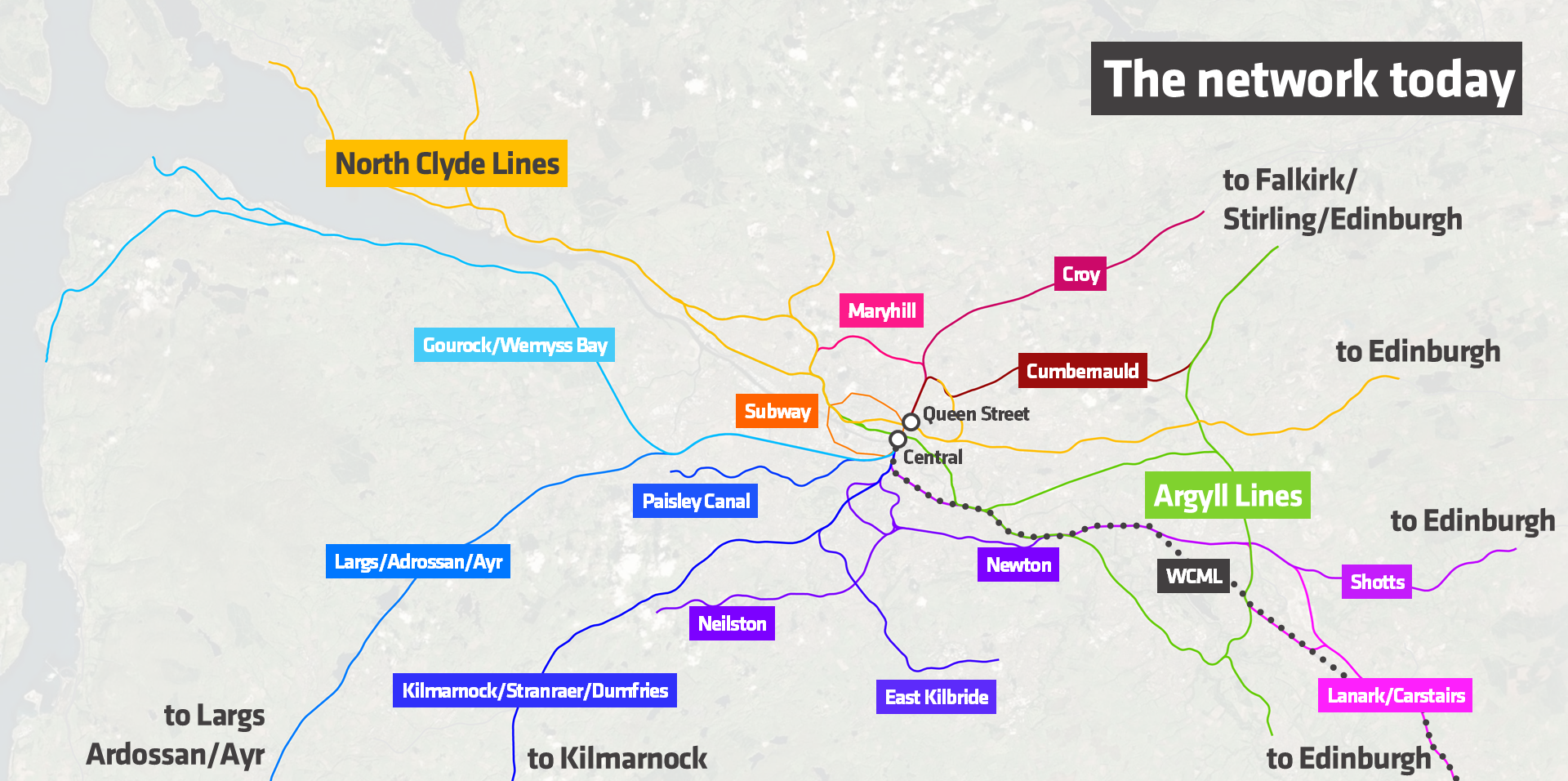

Most of the lines emanate from Glasgow Central station and face southwards (lines in blue/purple). A smaller number of lines face northwards out of Glasgow Queen Street station (red/pink). There is, notably, no direct rail connection between Central and Queen Street. The east-west network is formed of the North Clyde (yellow) and Argyll (green) lines, and resembles the kind of system you might find in continental Europe or London — with lines fanning out either side of an underground core through the city centre. Overlaid onto this are regional services in all directions and long-distance services towards England along the West Coast Main Line (WCML).

But constraints are already beginning to bite, forcing people with means to choose to drive – and people without not to travel at all. We’ll start with the biggest: Glasgow Central.

Problem 1: The Central squeeze

The station is formed of a grand, south-facing terminus of 15 platforms above ground at High Level, and two underground platforms facing east-west at Low Level. As well as regional and long-distance services (we’ll get to these), the above-ground station accommodates nine separate groups of suburban rail services spreading out south of the Clyde, and even outside of the peak period these include 26 trains per hour (tph) pulling in and out of the station on top of long-distance trains making their way southwards onto the West Coast Main Line.

The capacity of this station and the lines approaching it have been reached. Trains are already overcrowded, and this is only going to get worse. It’s beginning to impact the timetable, making services less reliable.

And that’s before you take into account the need for more services to other cities. It may seem like a bad joke to talk about improving long-distance services, given that Westminster has largely cancelled High Speed 2 and Holyrood never seemed too interested in plugging the gap south to the border with England. But at the moment, reducing the number of domestic flights and taking traffic off the M6/M74 is impossible, as intercity services in and out of Central are already at capacity. We must plan for longer and more frequent high-speed trains.

That will require a significant reconstruction of Glasgow Central’s platforms and track layout. The biggest change would be the extension of 400m platforms across the Clyde – a plan long in development but still not yet actually on the table despite its strategic necessity. This would provide an opportunity to build a new station entrance south of the river, making Central more accessible and allowing for more facilities.

But that won’t solve our suburban rail problem — in fact, it will make it worse. Fitting these longer platforms in will reduce the total number of platforms at the station, and higher frequency intercity trains will take platforms away from south-facing suburban services — just when they need to be expanded. There’s no getting around the fact that, with limited room to expand Glasgow Central, and with no trains able to go through it, we face a direct trade-off between our suburban and intercity rail services.

Problem 2: Not enough east-west elbow room

Though they are less critical, the capacity pressures on the east-west oriented North Clyde and Argyll lines are also a major problem.

The underground stations at Queen Street and – particularly – Central are reaching the limit of their ability to deal with peak time passenger flows. Platforms and connecting corridors were designed for much lower levels, and this puts a ceiling on our ability to run more trains safely, even if tracks could accommodate them.

Elsewhere, the tracks themselves are the issue. The section between Partick and Hyndland, shared between both the North Clyde and Argyll lines, carries 16 trains per hour on a single pair of tracks and cannot handle more without major upgrades. There are parallel, though less severe, pressures on the Falkirk High line out of Queen Street, too. This is the premier fast link between Glasgow and Edinburgh, and short of replacing it with a new high-speed railway (not a bad idea), it takes capacity away within the city.

In addition, stations all along the extremely busy and speed-critical West Coast Main Line (WCML) are curtailed by the need to keep the lines free for long-distance trains. The eventual arrival of HS2 services will only compound this, as longer and more frequent trains will reduce the space for suburban trains through Cambuslang, Newton and Motherwell further.

Problem 3: Gappy coverage

We’ve talked about where existing rail lines are struggling to meet the needs of the city. But what about those parts of the city where there are no trains at all?

Either through omission or closures, much of Glasgow is train-free. This includes deprived areas like those around Tollcross Road in the east or northeast of the city centre along Maryhill Road, and large tracts of the west of the city along the Clyde such as Scotstoun, Shieldhall and Renfrew. There are also prime areas for development that lack rail links, not least around the airport.

A central challenge here is the Clyde. Glasgow has opened seven new crossings of the Clyde since the millennium for vehicles and pedestrians, but the last rail crossing to be built over the river was finished in 1905.

Today, east of Central station there are three rail crossings of the Clyde, all outside the dense urban core. West of Central station, only the Subway crosses the Clyde — there are no other rail links between the north and south banks between the centre of Glasgow and the Firth of Clyde. This severely limits people’s ability to move across the city and puts pressure on the city centre by squeezing more people through Glasgow Central station.

There are countless other issues, spread within and beyond Glasgow’s confines. For example, because of the interconnected nature of the railways of the Scottish central belt, limited capacity at and through central Edinburgh has a strong bearing on what happens in Glasgow; it’s a complicated picture. But here’s a map showing the ones we’ve discussed so far:

How to fix it

Without much fanfare, and mostly behind closed doors bar the occasional consultation event, plans for the overhaul of Glasgow’s urban and suburban transport network are being developed by Strathclyde Passenger Transport. Dubbed the “Clyde Metro”, they comprise the latest in a long series of reports, commissions, studies and reviews looking at how to deal with the immense popularity – and consequent lack of capacity – of Glasgow’s public transport.

These plans will need to be bold. To see how bold, I’ve decided to lay out a design for a new suburban rail map that can resolve many of the challenges I’ve highlighted.

These proposals have been sketched out by an experienced railway engineer and someone who has worked on urban transport systems across the globe – me – but they’re not fully developed. They should, however, give a useful insight for readers on what is technically feasible, as well as providing a comparator against which to measure the ambition of the Clyde Metro proposals.

So what do we do? Three big problems require three big solutions, and the first is the biggest of all:

1) A new north-south tunnel

Everything depends on solving the Glasgow Central problem.

As successive studies dating back decades have all concluded, Glasgow needs a new city centre station to link the dense suburban network south of the Clyde with new and existing lines north of the river. Nothing short of this will deliver the capacity and connectedness required to keep rail-borne Glaswegians moving into the middle of this century.

To do that, we’d need a tunnel. This would allow south-facing services that currently pile up inside Central station to run through the new station to Queen Street and onwards onto lines facing northwards. While terminus stations like Central are limited by the time needed to turn trains around, a through-running station can provide capacity for as many as 24tph on just two platforms.

I’ll call the new station “City” for now. It would be set between Central and Queen Street stations below the level of the Subway and linked into all four of the stations within its footprint (including St Enoch and Buchanan Street stations on the Subway) via escalators, lifts and walkways. Building it and its connecting rail tunnels would enable a unified network of north-south lines similar to London’s Thameslink system. With eight-car trains running on the system, it could achieve a throughput of 13,200 passengers per hour in each direction, accommodate all suburban services from the south and enable new suburban services in the north.

As I’ve shown in the map, the tunnel could link to a new station at Tradeston before emerging and linking to the lines towards Paisley, Barrhead, Neilston, East Kilbride and Newton. North of the new City station, it would link initially via tunnels under Sighthill (through a new station) and out amidst the former St Rollox works, linking east onto the Cumbernauld line and north onto the Springburn line towards Croy.

However, in the longer term, the opportunity should be taken to create new lines in the north, and in our proposals I have taken the chance to create two new (largely tunnelled) sections of line. One makes use of parts of the former Glasgow Central Railway to link Kelvinside onto the Yoker branch at Jordanhill, allowing this line to be split from the North Clyde Line and partially alleviating the Partick-Hyndland bottleneck. The other creates a completely new link through Hamiltonhill and beyond to Cadder on the Forth and Clyde Canal – this could follow any feasible route that best links these deprived and unserved areas in the north of Glasgow.

This new family of lines – Clydelink, if you like – would run largely on their own segregated tracks. Drawing the north and the south of the city together would bring immense benefits and solve our Glasgow Central capacity problem.

However, lines to Largs, Adrossan, Ayr and Kilmarnock (and beyond in the latter two cases) involve longer distances than functions well for a fully suburban-type service. These will, by their nature, have to mix with the busy stopping services we’ve proposed on these sections. There’s no avoiding this conundrum.

We have three things in our favour, though. Firstly, that these services are all electrified — or soon will be — and electric trains can accelerate faster than diesel ones. That means shorter delays as trains leave stations and more trains per hour. Secondly, that the required signalling upgrades, ideally to ETCS (standardised European in-cab train control) would allow for improvements in overall train frequencies on the sections where services share the track. Thirdly, building our new north-south tunnel under the Clyde would take most or all Glasgow inner suburban services out of Glasgow Central’s high-level platforms. This would leave the above-ground terminal with capacity for these longer distance trains. In combination, these will reduce the risks of a conflict for space between trains. A further fix would be building more “turnback” facilities at the city region’s edge, to allow shorter distance trains to reverse without getting in the way of those continuing out of Glasgow.

2) A new western link

As things currently stand, the Argyll line joins the North Clyde line west of Exhibition Centre. But that exacerbates the notorious bottleneck between Partick and Hyndland and is a missed opportunity to bring unserved areas onto the rail network whilst providing a new link across the Clyde.

A better proposal would be to take the Argyll Line into a new shared station at Kelvinhaugh (allowing exchange onto the North Clyde Line) before hugging the river through new stations at Castlebank (for the Riverside Museum), Whiteinch and Scotstoun, before rejoining the Yoker branch (blue, below). This is prime development land, and it is ripe for better public transport links.

Then, a new tunnel north of Shieldhall would take a branch of the Argyll Line south of the Clyde to Braehead before splitting again to provide links to Renfrew, the Advanced Manufacturing Innovation District and Airport in one direction, and to Erskine and Bishopton in the other. This would not only provide fast, direct links from the city centre to the airport via the so-called South Clyde Growth Corridor, but would also relieve the heavily congested lines between Port Glasgow, Paisley and Central.

This major bit of infrastructure would create a far more resilient Argyll Line, with our proposals giving us a line running from Larkhall, Motherwell and Springburn in the east to Balloch, Bishopton and the airport in the west. The map below shows a zoomed-out view of this line, including where it would interchange with the Clydebank and North Clyde lines.

3) An eastern link from Bellgrove to Newton

Moving to the east of the city, there is a glaring gap in today’s rail network that can be filled to the benefit of the whole system: the area around Tollcross Road, with Parkhead in the north and Carmyle in the south. It is an area that suffers from deprivation, but it also has significant opportunities for sustainable, inclusive development (not least at the now sadly former Victoria Biscuit Works). There are also several major amenities that would benefit from rail links, including Tollcross Park, the International Swimming Centre and Celtic Park.

For much of its length, this new bit of railway would use the path of the former Carmyle and Bridgeton Cross Line alongside Tollcross Road, then make use of an old link from Carmyle to Newton. High-density North Clyde Line trains would run on to Shotts and new turnback facilities, alongside the outer suburban services running to Edinburgh.

As well as running through a deprived part of the city that has long been missing a rail connection, the Bellgrove to Newton link would provide a cleaner, simpler service pattern into the city centre. It would also free up capacity on the WCML from Rutherglen into Glasgow Central because services from Shotts would instead travel up towards the city centre via Belgrove, rather than going into Glasgow Central.

These proposals (including a new Clyde tunnel at Longhaugh to the west of Glasgow) create a North Clyde Line running from Caldercruix, Whifflet and Shotts in the east to Helensburgh, Gourock and Wemyss Bay in the west. They will remove several bottlenecks, giving it the capacity to grow all the way into the second half of the century. The map below is a zoomed-out view of the new North Clyde line.

Final tweaks

These three big changes will have the most impact in making Glasgow’s railway the obvious transport choice for all of its citizens. Here’s a map that brings them together and shows what the new network would look like:

Of course, they’re not the full story. I’ve left out existing and future orbital services, particularly in the east of the city. Much like London’s Overground system, these serve a valuable function in linking up the outer parts of the city without people having to travel through the centre. Then there are freight trains that make extensive use of the network through and around Glasgow, and these will expand just as quickly as passenger services if not quicker. Future plans need to enable this growth.

But before finishing, I thought I’d address the classic question: what about the wee Subway? Why haven’t I planned for a big extension?

The reasons are pragmatic. To make the subway useful as part of a wider network, all of its stations would have to be rebuilt for longer trains. All of its tunnels would have to be rebored to accommodate wider tracks. By the time you’ve done this, you’re better spending the money on the infrastructure I’ve described already, leaving the Subway to do what it has done nobly for a century and a quarter now: serving the western city centre. And long may it continue to do so.

Over the next 20 to 30 years, Westminster is going to be unavoidably spending tens of billions of pounds on public transport infrastructure. For every billion spent, a percentage will find its way to Scotland through Barnett consequentials to be spent on transport (as a devolved matter for the Scottish Government). Scotland and its cities can and should be planning for a bold, visionary future accordingly. In Glasgow, three big changes could be transformative. It’s time to be ambitious.

Gareth Dennis is an award-winning railway engineer and writer, as well as hosting the weekly railway #Railnatter podcast. He lectures on railway systems, safety and sustainability for the Permanent Way Institution and is a co-founder of the Campaign for Level Boarding. Follow him on socials at @GarethDennis.