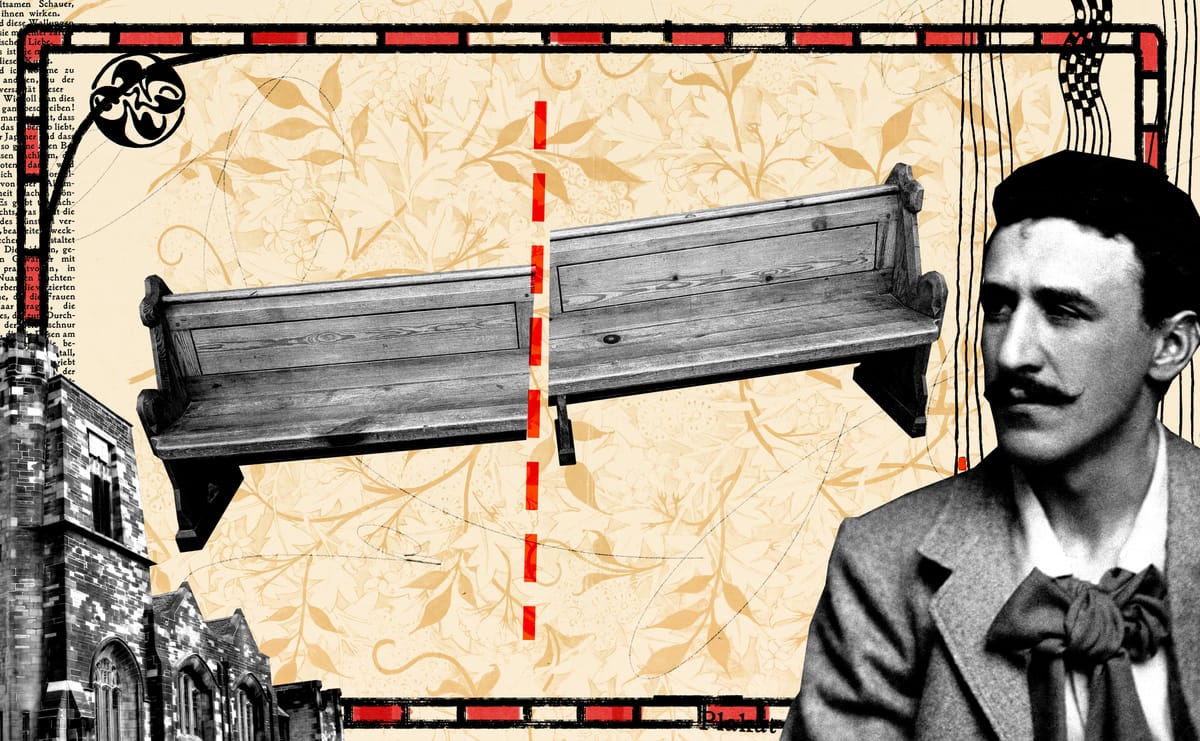

I wish I could say that it was love at first sight for me and Counterflows, Glasgow’s longest running experimental music festival. But it had been a week since I’d left the glass and chrome of Toronto’s condo skyline behind when I first walked into Maryhill’s Community Central Hall in March 2022, to check out what a friend insisted was the most important and exciting experimental event in the UK.

How acclaimed could it be, I wondered? I’d never heard of it. Walking into the community hall venue with its extra fold-out chairs and diminutive stage, further seemed to confirm my scepticism. It seemed a more likely backdrop for nativity plays than a mecca for the vanguard of experimental electronics.

The crowd was markedly eclectic too. Here art school hipsters were seated next to tweed-donning pensioners. Toddlers, including my own two-year-old, bobbed in and out of seats while parents drank free beers provided by local brewery Drygate, or tucked into meal deals smuggled in from the Tesco across the road. Triple mango vape smoke snaked its way around the room, enshrouding parties conversing about everything from gentrification to mortgage rates.

I was both charmed and challenged. In a festival landscape saturated by branded partnerships and homogenous crowds, within two minutes of arrival, it was clear that Counterflows was something different.

Thirteen years later Counterflows still squares the circle, making music on the outer fringes of contemporary — from Scotland, across the UK and the world — feel like an adventure. Set across the first weekend in April, it’s the UK’s premier experimental music festival, but it doesn't take itself too seriously.

Since its inception in 2012, the festival's founder Alasdair Campbell has emphasised that so-called “difficult music” doesn’t always need to feel difficult. As he explains to me, he was “getting tired of how serious and dreary” experimental music could sometimes be. “I felt it was time to explore just what was going on with this very term ‘experimental’,” he says. “I wanted to bring back a joy and fun to music making and watching — to examine the social nature of experimenting and to try to bring a new audience to it.”

Alasdair started the festival after a tenure as the artistic director for the Tollbooth in Stirling, where he programmed experimental predecessor, Le Weekend. Counterflows began life as a partnership festival running across venues in Glasgow, London, and Berlin. But as it evolved, Alasdair sensed that Glasgow was its real spiritual and physical home. It turns out the community hall venues are not a case of poor planning, but a deliberate endeavour to move away from city centre venues and locate music back in the local areas Glasgow’s DIY culture is known for. Alasdair explains: “Bowling clubs, railway arches, community halls and the like became the essence of the journey around Counterflows.”

Journey is the operative term here, and not just in the metaphysical sense. With the venues spread out across the city, going to the festival is like taking a mystery tour of Glasgow. Each location is soundtracked by a different set of artists who share an aesthetic, political or philosophical sensibility. Carefully curated timings mean there are no competing stages. In one day you might watch a cellist play in Anderston’s brutalist Pyramid, listen to a discussion in Maryhill’s (Mackintosh) Queen’s Cross church, dance to the frenetic sounds of singeli in the arches underneath Glasgow Central station, and then finish the night off with a barrage of DJs mixing everything from shoegaze to gabber in The Ferry, on the banks of the Clyde.

If the above sounds dizzying, it's because it is. As a novice during my first year, it was hard to imagine how we could shift gears from watching the improvisation of experimental jazz group [Ahmed] at the Glue Factory before heading into an adrenaline coasting DJ set from aya at Room 2. But as [Ahmed] finished up and the punters headed outside, we were greeted by complimentary buses to drive us into the city centre. Exiting the buses together, we descended into an empty club where pop remixes were being rinsed at upwards of 150 BPM from the moment we entered the doors. This was not an experience I've had before or since and it was exhilarating. Three years on that enthusiasm hasn’t dimmed. After a year hiatus in 2024 the festival returned at the beginning of April 2025, bolstered by multi-year funding from Creative Scotland — a total of more than £700,000 that secures its future for the next three years.

Maybe that’s why it felt like a homecoming for the festival. It featured the unsung queen of experimental and spiritual jazz Amina Claudine Meyers, the feedback-gnarled rhythms of Klein, and the full ensemble of disabled and non-disabled musicians that make up Sonic Bothy, to name just a few. The venues were equally diverse, from the usual Counterflows homebase of Civic House to The Art School, Woodside Halls, and of course, Community Central Hall.

This sense of “the bizarre and the beautiful” is down to how Alasdair and his co-conspirator, the veteran DIY music promoter Fielding Hope, programme the festival. They are not afraid to take risks and relish moments of dissonance. “The festival is about trying things out, sharing, exploring possible connections, frictions or contradictions,” Fielding tells me. "We painstakingly map it all out and philosophise it — so there’s a plethora of cultural, aesthetic and political ideas we hope arise in some way.”

The logic that emerges across an edition of Counterflows is singular and ephemeral. Each year, certain themes and ideas percolate across the programming, but this isn't heavy-handed or didactic. Moving through the different spaces of the festival with the same people feels radical in and of itself. It harkens back to what Fielding, who worked and studied in Glasgow from 2006 until he left to work for London experimental venue Cafe Oto in 2014, first loved about the city. He is planning to return soon.

He explains: “One thing I noticed in Glasgow is several of the same people would all go to a gallery opening, then to DIY noise or punk show or whatever, then to a club night, then an afterparty, most likely somewhere on the old blocks on West Princes St in the West End. Moving around the city and sharing space with people in all these different cultural spaces was something that felt natural and really stimulating.” On paper, these events may ostensibly inhabit different social and cultural spheres. But there is a sensibility that holds them all together and a commitment to underground culture.

Counterflows is able to recreate and reimagine a broader continuum of experimental music that pushes boundaries.

“From the beginning we agreed that though we both think politically about what we are doing we wanted the artists and programme to reflect this more than us writing manifestos,” Alasdair explains. “A key issue for us has been examining the Western hegemonic ideas that have dominated and stifled what we call ‘experimental’ music.”

Take this year's commission from Ankna Arockiam, Nakul Krishnamurthy, and Tom Mudd. The three work with classical South Indian music structures but deconstruct them into beautiful and slightly haunted melodies. You don't need to be versed in the history and theory of Carnatic music to feel the strength of this performance. It is right there in every note the three let hang in the air.

Yet events like Counterflows are increasingly difficult to stage. While the festival may be more securely funded than it was previously, Creative Scotland granted less than they applied for and some others lost out. Venues are constantly under threat of closure. This, along with rising production and wage costs, plus increasing reporting demands and red tape from funders, means that they have to scale back some of their larger ambitions or look for money elsewhere.

This is the perennial problem of the underground: how do you maintain the DIY and contrarian spirit of something like Counterflows while also needing to operate in a world with increasingly scant public money for the arts?

The demand from the audience is there. Counterflows sold out of festival passes within two days last November before they even announced any artists. “We were humbled to see such a response,” Alasdair told me. “A festival is many things, but the most important thing is bringing people together."

An audience as committed as the one for Counterflows is a marketing company's dream. As Fielding points out, they could easily do the obvious next thing: “Book some big names and upscale to 1000 capacity venues. Join the ranks of one of the major European experimental music festivals.” But, he jokes, “I think that would frankly suck.”

Scalability and modularity may be the common currency of private-equity backed festivals, but this wouldn't work for Counterflows. There is an intimacy to the festival that can't be matched anywhere. I can't think of another place where the avant-garde is so accessible without compromising itself.

Next year, I will take my currently two-month-old newborn for his baptism of experimentation. I know I’ll be in good company. In one of the most striking performances this year, the Japanese improvisational artist Yan Jun covered his face in tin foil to distort the beautiful and guttural chanting that comprised the majority of his performance. As the show wound down, the gaps in between his alien singing were filled with toddlers and babies in the audience, responding to a language that was somehow familiar to them. After he finished, there was a moment of suspension — the music still wavered in the air, the audience yet to clap. In that gap, a baby cooed. Jun bowed to the baby as the audience burst into applause — the storied artist acknowledging the future generation of Glasgow experimentation.

Have you been to Counterflows? Which underground Glasgow scenes do you think people should know about? Let us know in the comments.

This piece was updated on 10 May to reflect that Alasdair Campbell programmed Le Weekend festival, rather than founded it.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.